Upon Arrival

Crafts of noticing on the move. Some practices for landing, lingering, and leaving.

Including excerpts from Spectres in Change Fieldnotes #2 and Dust & Shadow Fieldnotes #3

Landing

How to land in a place is a perpetual question for those of us who live and work translocally. People not tied to a specific geography or national identity, who find their home in the connections with and between places and cultures. Living translocally implies travelling in the spirit of reciprocity, intent on being a considerate guest, acknowledging difference, and attending to the needs of their hosts (human or otherwise). Landing well requires a meaningful exchange between host and guest, often leading to long-term association and commitment, cultivating a lasting bond of mutual benefit (such as collaboration or friendship). For those pressing forward, on their way somewhere, the fleeting moment of landing can easily be missed. Whether you step off a boat or an airplane, cross a border between nation states, or the threshold of someone’s home. The significance of entering someone’s house as a guest is recognised in custom and folklore, including rituals of asking permission, first-footing, and wassailing, which attach particular meanings to when and how to enter the home. Yet how you land matters. The place where you have landed has a life and history of its own, of which you may not be aware. Landing well recognises the possibility of disorientation, of culture shock and crossed wires, giving space for these collisions to be noticed, incorporated, and worked with. Whether you're arriving in a new and unfamiliar setting, or returning to a place that was once familiar, Expecting nothing to have changed between two visits can cause cognitive dissonance for all involved. landing is a ritual beginning with a specific place and those who call it home. Although each landing is different, practices of communing, attuning, and storytelling offer some well-trodden starting points.

Communing

At the moment of landing, pay attention to the points of contact between your physical body and the body of Land. Notice where they touch and what that touch communicates. When you pay attention to how your body lands in a place, landing becomes a greeting, a conscious start of your communing with the land and its inhabitants (whether or not you share a common language). You recognise their agency, even if the local language and customs are beyond your comprehension.

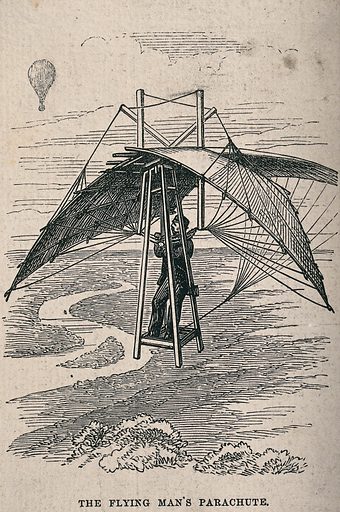

Practices of communing and their rituals thread together a common humanity. Some rituals are a way of asking permission to land. Consider indigenous land acknowledgements in Australia and the Americas, Uyagdok permission rituals in the Philippines... Others focus on greeting, acknowledgement and appreciation, Lei garlands in Hawaiʻi and across Polynesia, Khata scarves in Bhutan... or probe if you are friend or foe. Handshake to check for concealed weapons, host tasting wine before offering it to the guest... Most of these rituals help you to notice what the land and its people want to share, where they want you to be (or not) and what you are invited to do (or not). Communing as a landing practice can be experienced in (spiritual) rituals, but can also be trained with deep listening, dance and physical theatre, or even simply by paying attention to walking.

Landing is something you can practice whenever your feet leave and return to the ground. Try landing with intent, noticing what happens in the moments your body touches the Earth. Before starting to walk, take a few deep breaths. Notice your intention to move, and how this translates into the tensing of muscles; your foot lifting, moving forward through the air. Pause briefly, just before touching the ground. Notice how gravity pulls your foot towards the Earth, and what happens when you land. What happens at the interface between your foot and the ground? Relaxation, relief, the texture and support or resistance of the surface. Something else?

Sense and sensing are forms of divination, of prediction. Augury may be defined as the practice of interpreting omens from the observed flight or dance of non-humans, tracked by GPS or satellite; divining both the past and the future, not any present but sheer persistence which is beyond appearance, offering either transcendent meaning or only the earth.Martin Howse, Augury

Attuning

The instance of landing in a place lasts only a few moments, but it can take much longer to truly arrive. Consider jet lag, a disruption of the body's circadian rhythms when flying across multiple time zones. Digestive problems arise in response to different microbial cultures; moral or emotional conundrums in response to cultural differences. It takes time to attune to the rhythms of a place, its harmonies and dissonances. See Practicing Attunement Attuning requires patience, attention and mutual adjustments to the effects of the interaction. It might require turning down the volume of known human languages – including your own internal dialogue.

Attuning can best be practised in silence and solitude. Notice with your whole sensorium; eyes, ears, nose, tongue, skin, and brain. Sensitive to the effects the environment has on you and vice versa. Let yourself be touched by the air, earth, and water, by the bodies of the land and its dwellers. Notice subtle resonances and disturbances; the colour of the light, the seasonal textures, the direction and strength of the wind. Even having lived somewhere for a while, your experience sometimes falls out of sync with your surroundings. Physically present while your mind is elsewhere, you can easily overlook more ambient, ephemeral signals. Changing postures, wandering attention, darkening clouds, drifting sands…

Attune to the land at various speeds — sitting or lying still, hiking, climbing, walking, meandering, always attentive to the many dimensions of experience. In stillness and motion, in a range of postures and gestures, observe the porousness and percolation between your inner sensations and outer circumstances. Return to the same places over and over again. Feel with, feel around, until you feel grounded where you are.

The necessity of changing methods is all the more obvious when it is a question of finding the explanation of a phenomenon that nature offers in all of its complication. There, where the givens are by their very existence more complicated than the results we seek, direct synthesis becomes inapplicable, and it is necessary to take recourse either to direct analysis if possible, or to indirect synthesis, to feeling around (tâtonnement) and explanatory hypotheses.

André-Marie Ampère (in John Tresch, The Romantic Machine.)

Storytelling

...we are and always have been name-callers, christeners. Words are grained into our landscapes, and landscapes grained into our words. [...] We see in words: in webs of words, wefts of words, woods of words. The roots of individual words reach out and intermesh, their stems lean and criss-cross, and their outgrowths branch and clasp.Robert Macfarlane, Landmarks

Words, entwined into stories, are an age-old "landing" technology. You can get to know a place through your human hosts’ subjective reading of the landscape; accounts filtered through local culture, history and personal experience. Landing in a different culture requires negotiation and adaptation. Sharing stories helps identify points of divergence and potential common ground.

An inhabited landscape echoes with histories. Storytelling can connect a fleeting landing to the deeper temporal layers of a place. Storytelling situated in landscapes (like a guided walk) can help new arrivals to land in space and in time, through myth, story, and song.

Learning journeys with local guides can unlock a place’s temporal dimensions. Stories told in their point of origin have the capacity to anchor themselves in your mind and body to a greater extent than when encountered elsewhere. Words and their meanings become infused with smells, colours and textures. See also: MonsterCode Their history, present and future are animated through the gestures and vocal cords of the people you meet.

If you understand the local language, or are listening to a translation, pay attention to metaphors and sayings, to the structure of the stories and their characters. Notice how the land gave shape to the form and content of the stories. If you don't know the language, listen to the rhythm of words, finding the lay of the land in the play of vowels and consonants.

If we listen, first, to the sounds of an oral language – the rhythms, tones, and inflections that play through the speech of an oral culture – we will likely find that these elements are attuned, in multiple and subtle ways, to the contour and scale of the local landscape, to the depth of its valleys or the open stretch of its distances, to the visual rhythms of the local topography. (…) Human language arose not only as a means of attunement between persons, but also between ourselves and the animate landscape.

David Abram, The Spell of the Sensuous

Leaving

If you are landing in a place without the intention of staying permanently, how you set off matters as much how you land. A ritual of un-landing, of de-parting, of em-barking, of leaving. Landing in reverse, suffused with different experiential textures. Appreciation, gratitude, the melancholy of separation. Acknowledgment that you are merely a passer-by – guest for some, food or nuisance for others. You come and go. Your presence and actions may linger as a faint memory, fading. Leaving no trace.

In landing and leaving, you touch impermanence at a human scale, measured in minutes. However brief, these moments remind us of the humility and preciousness of our fading existence.

When you next leave a place A forest, a city, your home..., imagine that you will never return. Notice what happens in your body and mind in response to this thought. How do you feel? What do you say (or not say) and do (or not do) when leaving this place, these people? How do you take your leave? What do you leave behind?

No species is permanent. Only the ecological niches, the environments friendly to one or another kind of life, have any kind of permanence. They saw that they would rise and fall like every living form. So, instead of trying to extend their existence, like so many other species before and since, they looked to ways of preserving and nourishing an environment that would encourage the birth and growth of species similar to themselves. Nothing's permanent. But everything can hand what's unique, what's best about itself, to what comes after.

Karl Schroeder, Permanence

The House Is Haunted By Itself

🍂

Further reading & references