Conscious Closure

Dissolving a studio with intent and purpose.

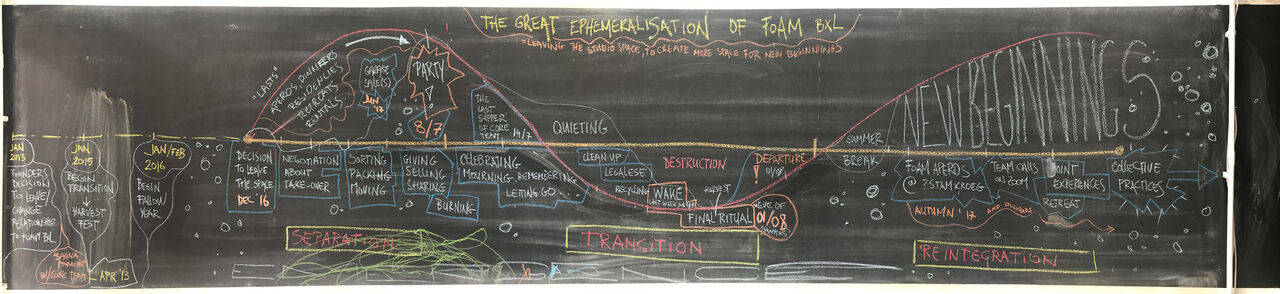

Including excerpts from FoAM has left the building, a memoir of the great ephemeralisation during the final months at FoAM’s studio on Koolmijnenkaai in Brussels, Belgium.

Too often endings mean “foreclosure”; they are done quickly, aggressively, without celebration or acknowledgement of the work, and people who have contributed. However when we look at endings as essential to beginnings, dying as a natural phase of ongoing life, indeed as the transformative element for renewal, then we have many choices – and responsibilities – in how we move through such transitions and change.Vanessa Reid, Conscious Closure.

FoAM has left the building

Just shy of noon on 1 August 2017, we closed the door of the FoAM studio on Koolmijnenkaai in Brussels for the final time.

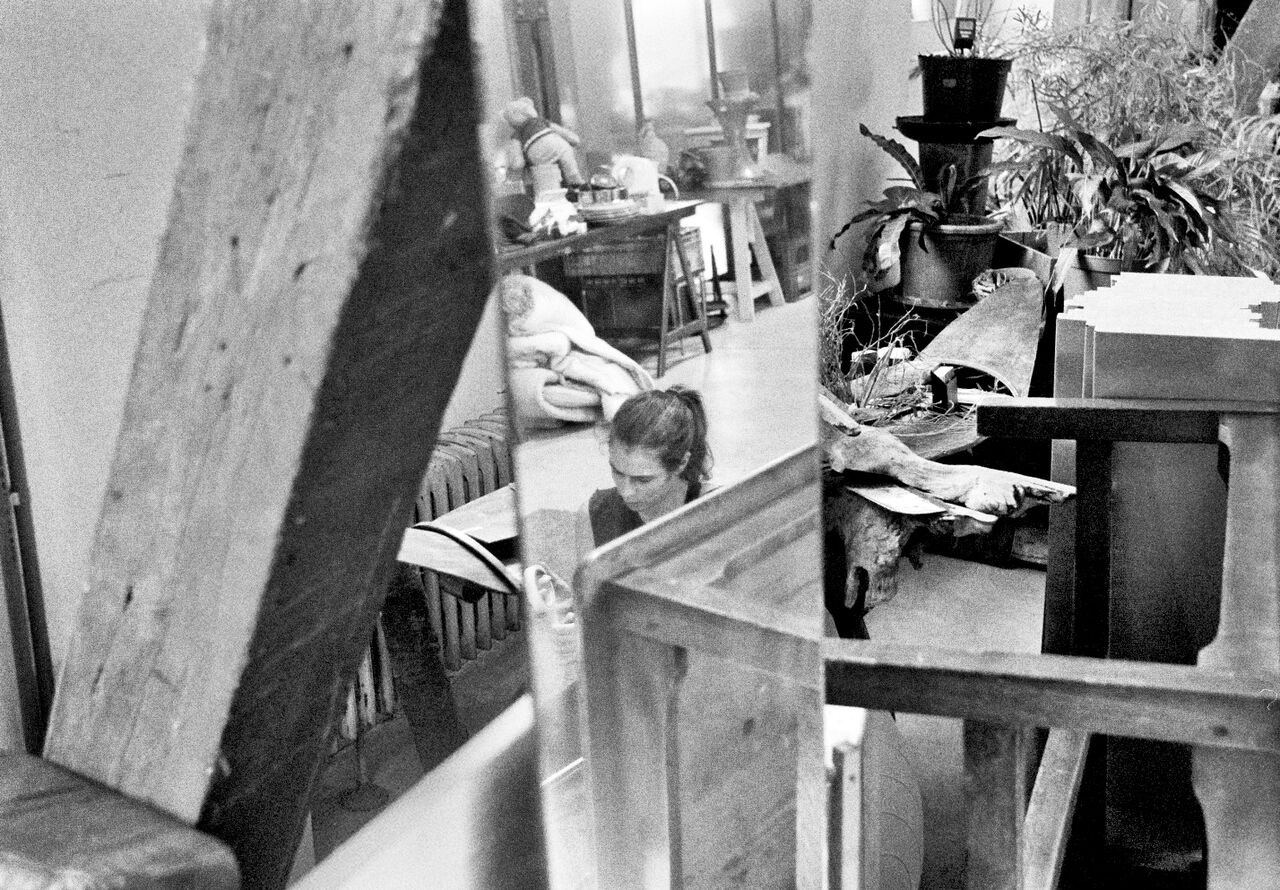

When we first moved into the studio, we were thrilled. Occupying the top floor of a former flour mill in Brussels, we recognised its large, bright space as an entity with its own character: adaptive yet demanding. It lent itself to many of our experiments. We explored different ways to manage the studio as a shared living and working space. We hosted gatherings, screenings, concerts, exhibitions, and feasts, built installations, and experimented with many forms of public events. Our workshop and residency programmes expanded. We maintained a library. On occasion, we converted the rickety loft (dating back to the 1800s) into a gourmet restaurant, a retreat, and a maker lab.

Over the years, we got to know the space and all its quirks and particularities. Its spaciousness. Its calm, focused, creative energy. Its relentless demands for maintenance and upkeep. Its ability to accommodate contemplation and celebration alike; providing a home for people across generations, cultures, and continents. Its rough, mystical atmosphere that stirs in the silence late at night. Its eerie voice of creaks, clicks, and whispers. Its capacity to retain and sediment the traces of people and things that passed through its doors, while remaining, always, uniquely itself.

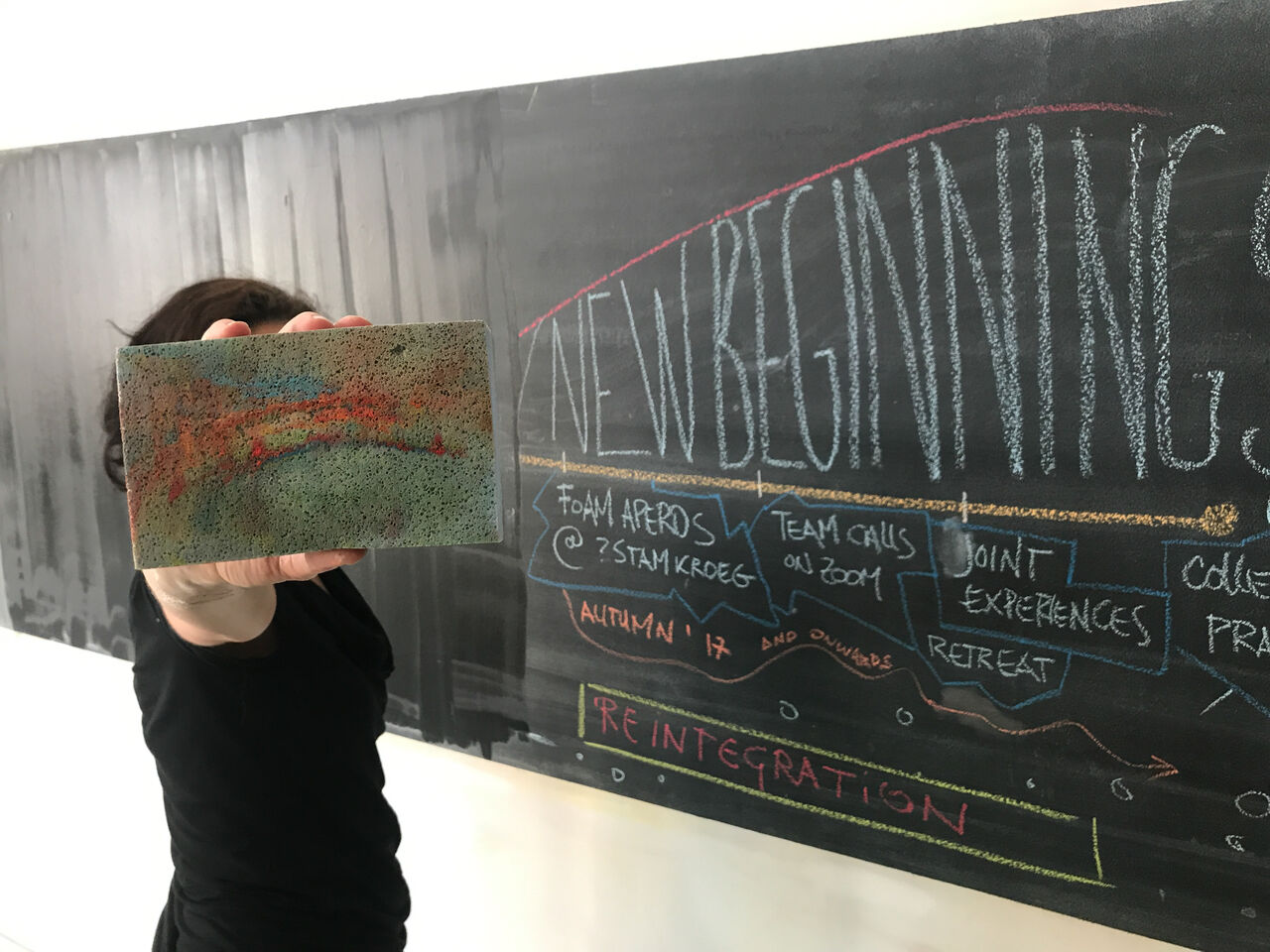

But the overheads of maintaining a large physical structure were at odds with our longing for more lightweight, nomadic ways of working. At the end of 2016, after many difficult discussions, we made the decision to leave Coal Mine Quay Koolmijnenkaai / Quai des Charbonnages behind. It was time to move on. This wasn’t an easy or rash decision, and we remain grateful to have been able to inhabit the space for as long as we did. It was emotionally loaded for many involved, especially the four of us in the core team. Acknowledging and anticipating possible resistance or scepticism with our wider networks, we approached the process as a conscious closure.

Valediction

The most tangible part of leaving the studio involved moving stuff – a lot of stuff. However, an equally important, if less visible, part of this conscious closure was the purposeful farewell, a parting ritual. We recognised the need for individuals to say goodbye to the space, a place that had held great significance in many lives. It had been a backdrop to major transitions, unexpected discoveries, fruitful collaborations, painful break-ups, creative breakthroughs, children maturing, wild parties and celebrations, delicate discussions, heated arguments, and long-simmering grudges that mirrored family feuds.

The space bore witness to countless shifting relationships, and personal and professional changes among FoAM’s collaborators and residents. The studio had served as a home to dozens of people, each with their own relations to the space. As such, there would be just as many ways to part, and bid it farewell – both individually and as a group.

From the start of June until our August departure, we hosted daily lunches, drinks, and dinners for all who visited or worked in the space. It was a parade of lasts: the last meeting in the greenhouse, the last FoAM retreat in the tower, the last Apero on the couches, the last lunch in the kitchen With an ever-decreasing number of chairs, tables, dishes, and utensils. Before bidding their final goodbyes, people often wanted to find some solitude in and with the space. Each person had their own private farewell, a ritual that lasted anywhere from a few moments to entire days or nights.

But for a space as social as the FoAM studio, a series of private farewells would have been insufficient. Hence The Great Ephemeralisation Party:a celebration of the space and all the possibilities it had brought to life.

In keeping with FoAM’s custom of welcoming all comers, the party kicked off with a team dinner for everyone who turned up. We shared messages from those who couldn’t be there in-person. Mystery boxes of FoAM arcana and useless yet cherished objects were raffled off. Contents included obsolete MIDI controllers from our earliest immersive environments, cookbooks and DIY manuals, and endless ephemera from the library’s lower shelves.

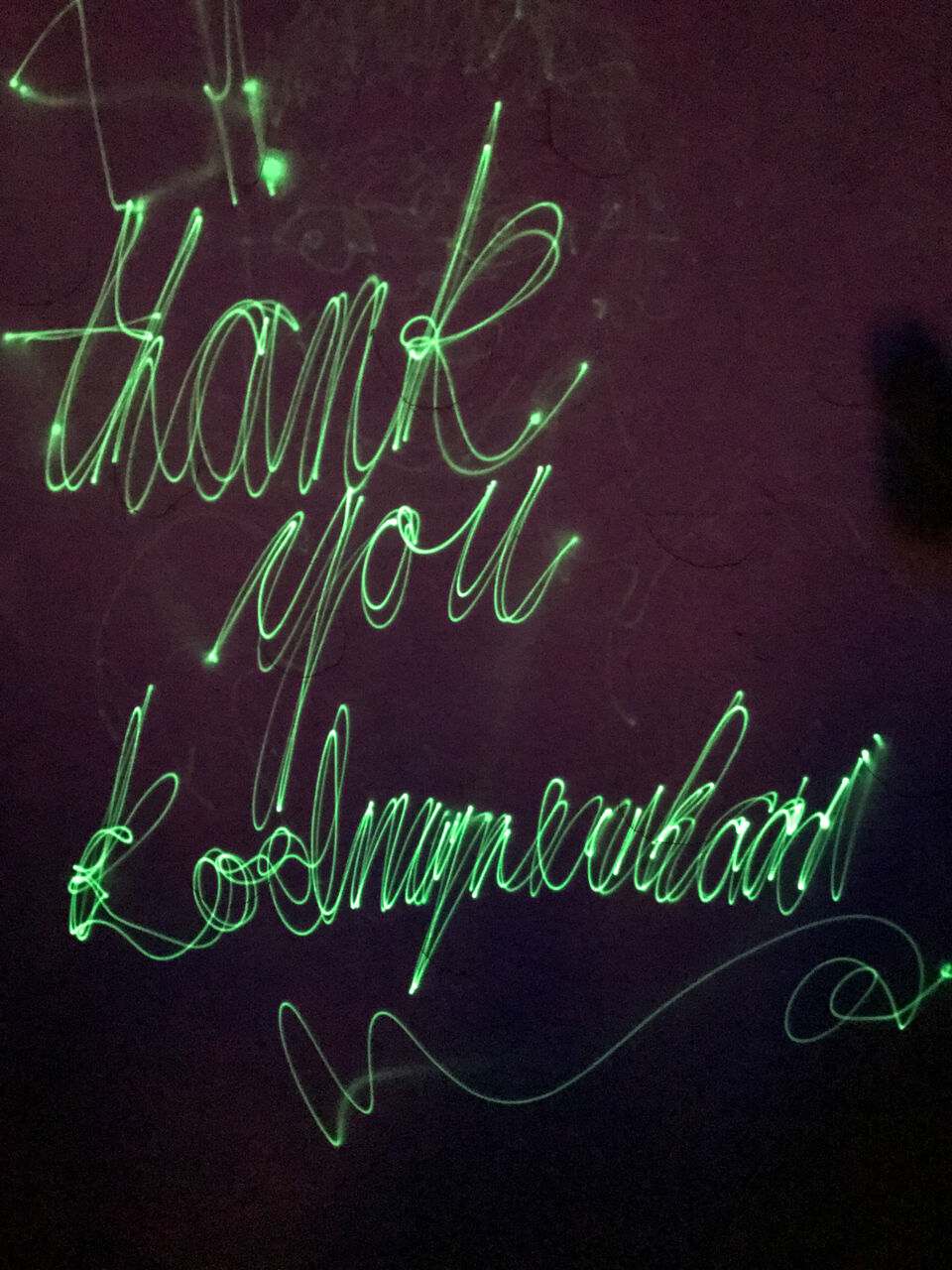

We served FoAM’s classic cocktails and other mind-expanding substances. A ritual bonfire burned those things weighing heaviest on our hearts, its flames consuming sketches and technical specifications for one of our most significant setbacks. Fireworks made from surplus rocket motors lit up the sky. We talked, reconnecting with people we hadn’t seen for years. We wept while watching a FoAM family slideshow. We danced as Lowdjo mixed, positively eclectic, always on point.

When we shared the studio with Lowdjo and the foton crew, we threw more parties. That unique atmosphere returned, again, one last time, making the space buzz and blossom, crumble and crack. We revelled in the moment, immersing ourselves in all that was. The celebratory energy lingered for days, if not weeks, but returning the morning after, the space felt different, deconsecrated.

Grief is an impersonal, potentially decolonizing force. Grief infiltrates structures, decays edges, and forces new postures of reverence and irreverence. Grief is not mere sadness; it is mutiny against established patterns.

Sorting

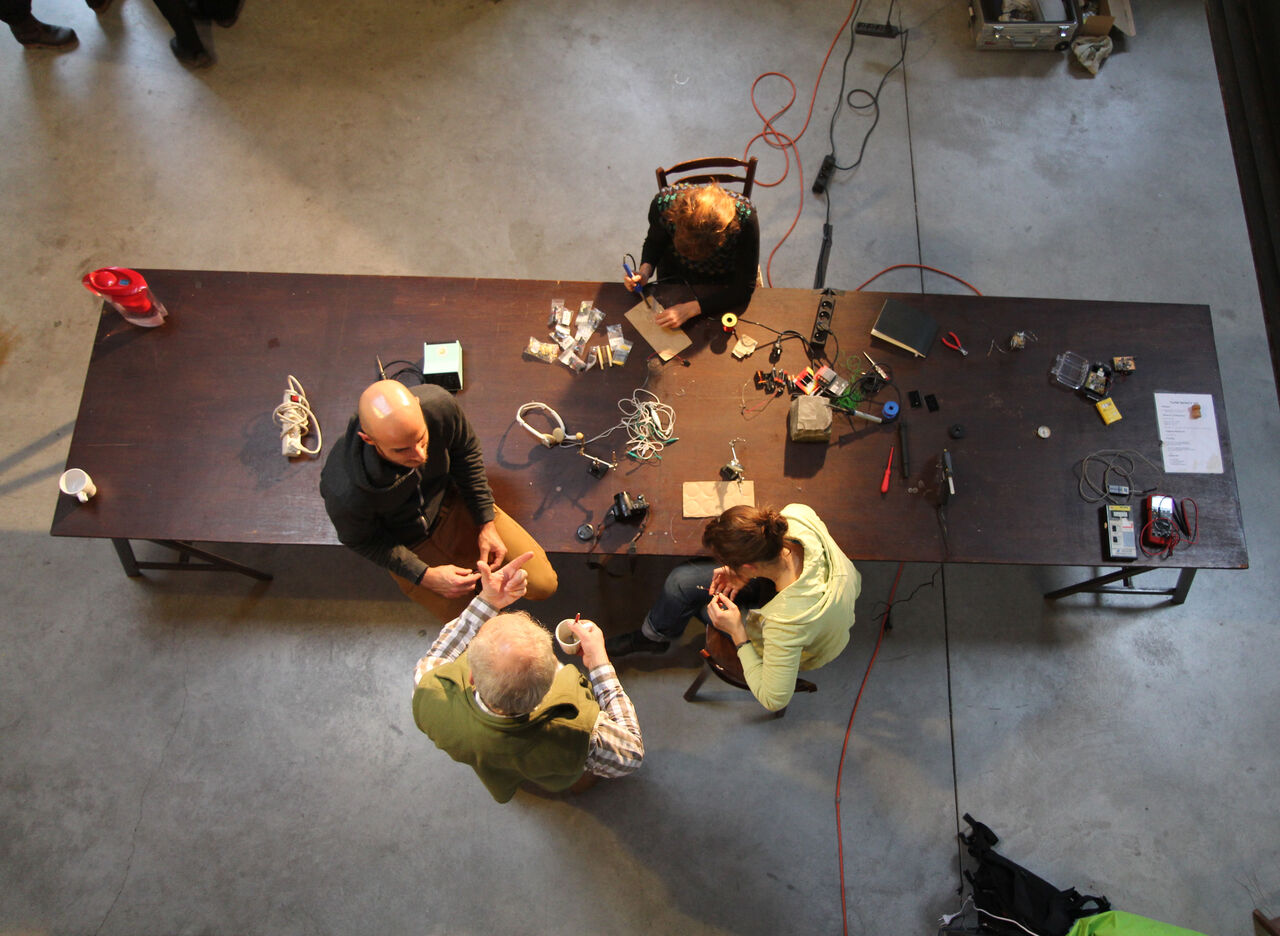

All that was left was the physical act of moving out. It was a creative experiment in ephemeralisation. Over the close to two decades in which FoAM had operated out of the Brussels studio, we, and the hundreds of people who had worked with us, had accumulated an incredible amount of stuff. Almost everyone who passed through had left behind items of rare and dubious value, some accidentally forgotten, some deliberately entrusted to the space. There were parts of old installations, computer hardware and electronics, cooking and gardening equipment, ropes, foodstuffs, the organisation’s legal and administrative archives, the library (including boxes of FoAM’s own publications), forgotten jars, frozen bones, talismans, and many other singular or unidentifiable objects. It quickly became clear that the process of becoming lighter was going to be heavy work.

The move was a creative process, requiring more than just heavy lifting and a strong back. It included the art of co-ordination, the science of sorting, the magic of tidying, and the convoluted craft of informal economics. It was a chaotic dance of people and belongings, with everything passing through the hands of the core team at least once. The simple act of picking up an object, from a piece of paper to a bookcase, could become a gesture of gratitude, curiosity, or leave-taking.

What to keep? Or Get Rid Of!What to reduce, reuse, recycle? What to sell? What to give away, and to whom? When does something once valued become waste? And how can we dispose of this waste in a way that aligns with FoAM’s ethical principles? How does dispersion become an exercise in growing worlds? How do we relate to objects, knowing our every decision determines the course of their lifecycle?

Dispersing

We started by identifying the things that would stay within our network. FoAM members and collaborators living nearby, in Belgium and the Netherlands, became custodians of the archive, library, research and production materials, equipment, and miscellanea related to our work or FoAM’s story. Next on our list were the other FoAM studios, those more geographically distant. We were touched to see how many people took items to re-create aspects of the Brussels studio in their homes and ateliers, in the same spirit, but on a smaller scale. The studio was dispersing, leaving, in its place, a network of mini-FoAMs.

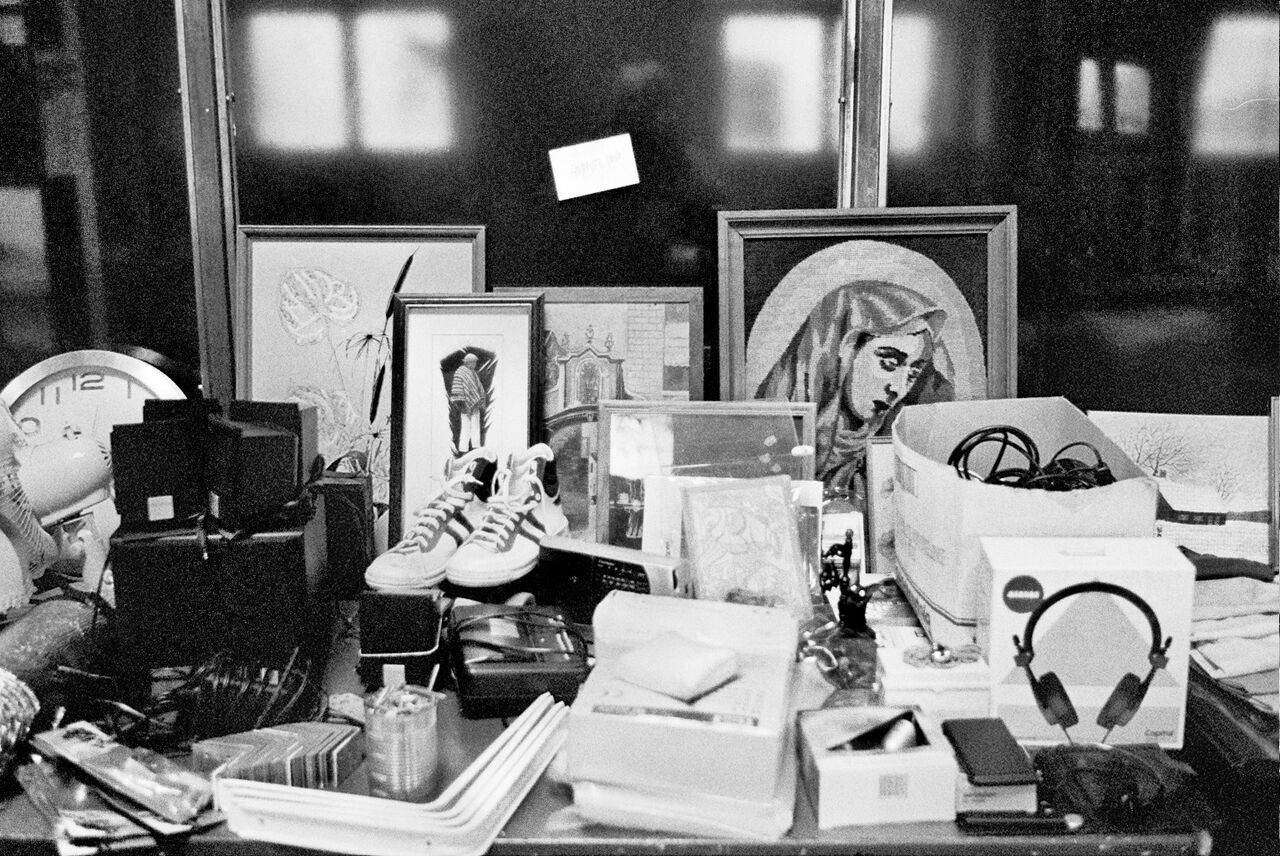

At the end of June, once we had emptied out the storage and pulled everything down off the shelves, putting it into some kind of order, we invited friends and neighbours to the space for a garage sale. In true flea market style, there was furniture, freshly potted plants, antique tea-sets, books and baby-seats. Shoppers could find high-grade astro-turf, roller-skates from the 1990s, and archival boxes from the 1920s, as well as top hats, broken clocks, and obscure electronics. Among these items was an assortment of media-art chindōgu “Ingenious everyday gadgets that seem to be ideal solutions to particular problems, but which may cause more problems than they solve”, including arcane body-synths, early e-paper tablets, and even a mostly operational weather station. As the sale progressed, this vast spillage of stuff spread further, scattered across all floors of the building.

We then invited a broader group of individual artists, collectives, schools, and other organisations to a more public-facing garage sale and donnerie A place and act of donating or giving things away for free. Branching out further, beyond Brussels’ arts and cultural sector, we widened our scope, donating more explicitly domestic items (such as furniture, toys, and bed linen) to social organisations working with refugees, the homeless, and other marginalised groups.

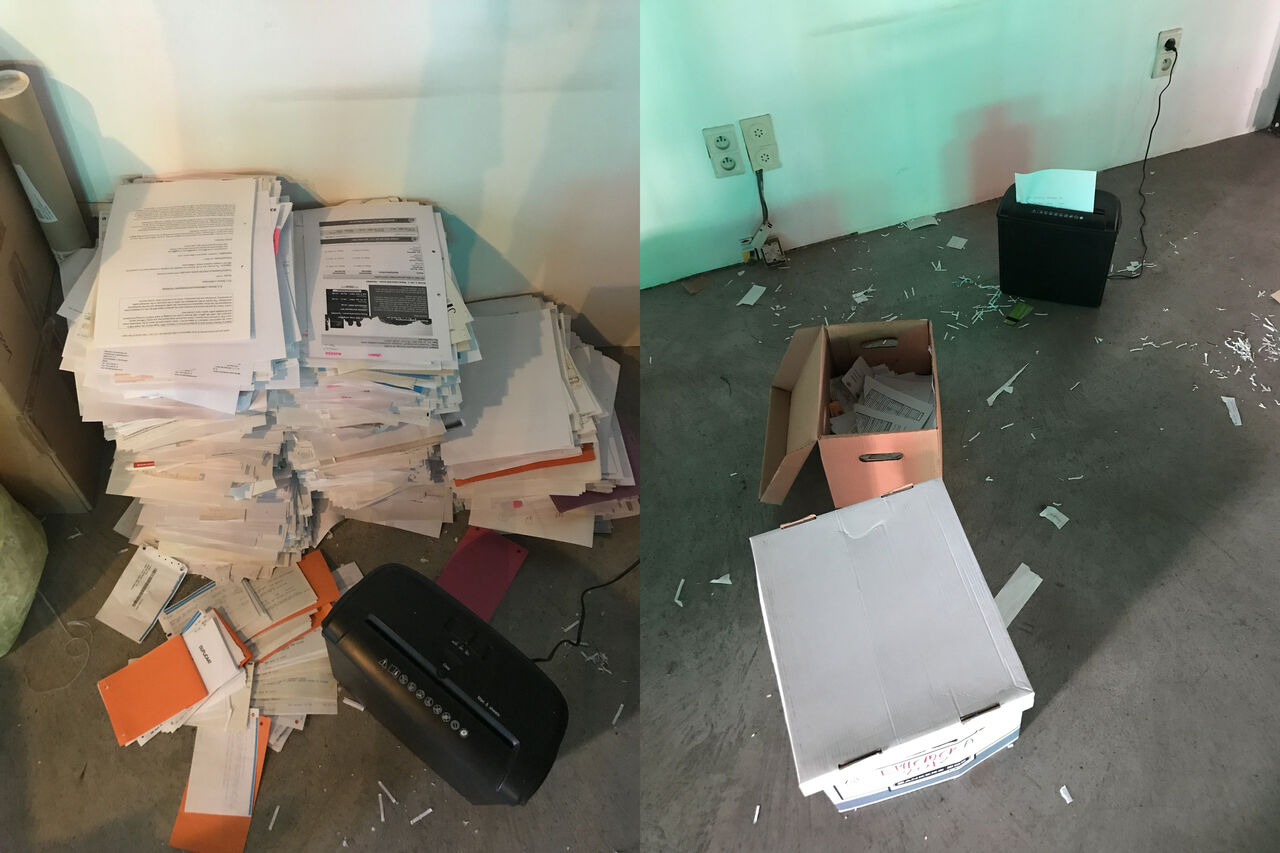

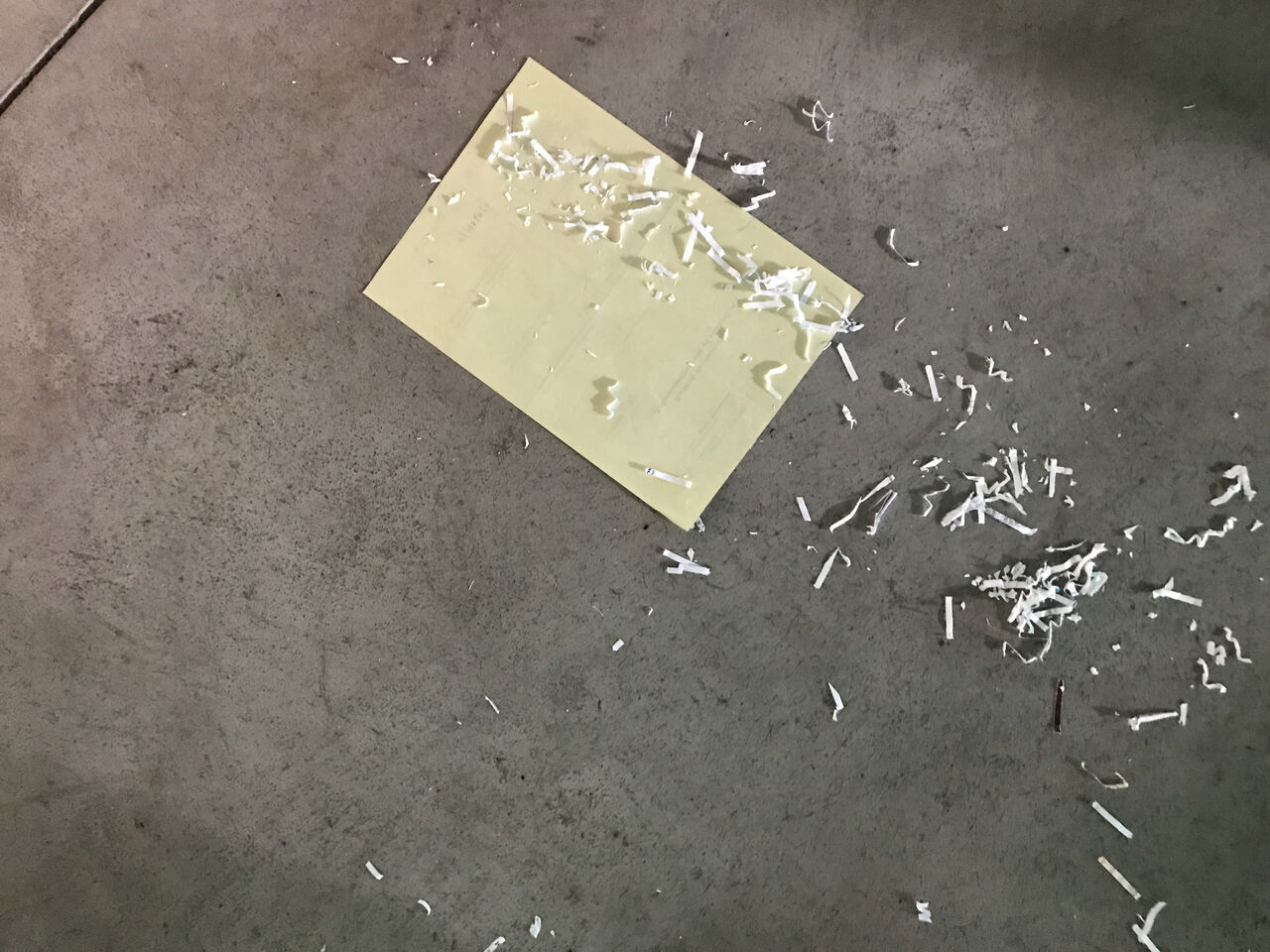

Even after weeks of selling, sharing, and donating, the space was still far from empty. What remained were the broken, unwanted, and out of date. Useless things. In other words, waste. We wanted to recycle as much of this waste as we could, in line with FoAM’s environmental and metaphysical commitments. It was our responsibility to dispose of the unwanted things with respect, considering both the things themselves and the ecologies of which they were a part. Each trip to the recycling centre became a solemn funeral of matter. While the disposal process had to be efficient, the repeated gestures of lifting, turning, shredding and throwing became trance-like, assuming a ritualistic quality.

Quieting

As the dust settled, those of us who remained found ourselves with the time and space to consciously conclude our own relationships to FoAM’s physical manifestation in the Koolmijnenkaai studio. On the final day of July, with all the people and belongings gone, the space’s quiet beauty returned. We felt compelled to clean, to stroke every surface, to erase all traces of our presence, leaving only a few small seeds of FoAM’s atmosphere for the next tenants to cultivate or expel –unexpected mementos hidden in improbable places, invisible to all but those who spend time in the space.

As the sun set, we climbed up onto the roof and kindled a fire with the remnants of plants, incense, and ashes left over from previous seasonal rituals. The smoke was fragrant but weightless, spreading its scent across the city on a rising breeze. After two long months of bending and lifting, we straightened our backs and felt our lungs expand.

As we made our way back down to the studio, the air felt clean but stale. We threw open the windows and walked through the space, ‘stripping’ what remained of FoAM from every surface, every room, using smoke, wind, and breath. We cheered with the final remaining bottle of grappa (found in a box in the library after ten years, part of the final batch crafted by Maja’s father before he died). We sprinkled the last drops on the dying fire, watching as glowing embers turned to soft, grey ash.

We left the building at midnight, carrying a bag of coins that had accumulated in the studio over the years. Retracing our familiar path from FoAM to home, we left small metallic mounds on bridges and doorsteps, in fountains, across streets, and in front of windows. These coins became breadcrumbs, marking a path we had taken hundreds of times in the past decade.

We left the building with little trace of what had been. Deliberately marking the conclusion of a lifecycle; a release. Use By: Some Principles for Conscious Closure

📦

Further reading & references