Becoming Birdlike

On birdsong as a creative resource, enriching humans’ musical ideas and listening capabilities.

Including excerpts from Voicing the Dawn and Composing with Birds, originally published on FoAM's blog.

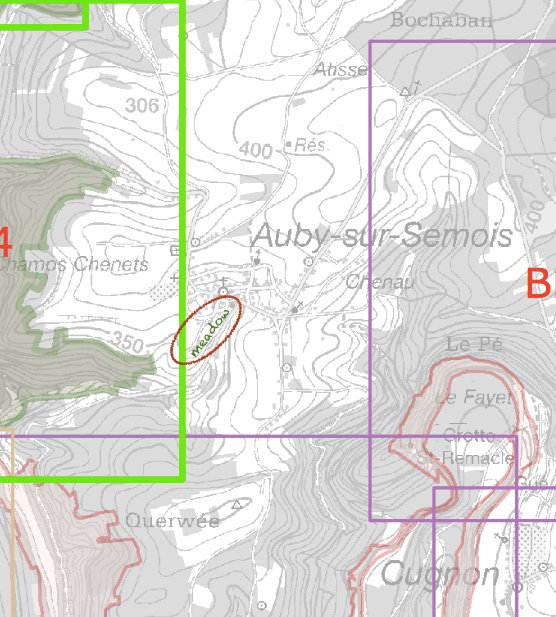

Listening to the dawn chorus in Auby-sur-Semois in Belgium, I have become fascinated with birdsong as a way to learn music and train my ears. Though complex and nuanced, birdsong remains accessible and inclusive, where complex contemporary music can be much less so. This lead to my experiments with voicing the dawn– linking sound, habitat, and the physiology of birdsong.

Listening to the dawn chorus in Auby-sur-Semois in Belgium, I have become fascinated with birdsong as a way to learn music and train my ears. Though complex and nuanced, birdsong remains accessible and inclusive, where complex contemporary music can be much less so. This lead to my experiments with voicing the dawn– linking sound, habitat, and the physiology of birdsong.

Waking around 15 minutes before sunrise, and with the frost clinging on well into May, the experiment starts by following the progress of the dawn chorus, the schedule being that of the birds – waking earlier and earlier as spring unfolds. Rising with the first tweet, it is possible to engage with the whole performance, and to be part of birds’ listening to each other's songs.

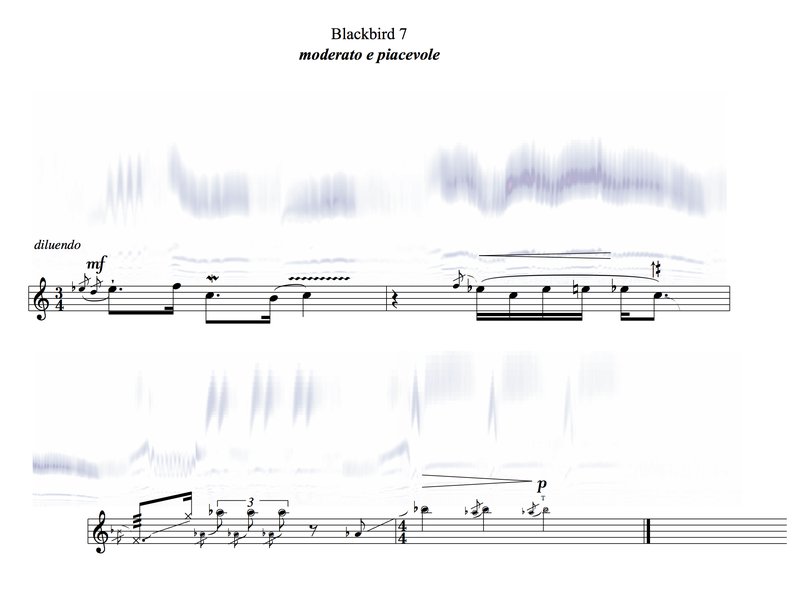

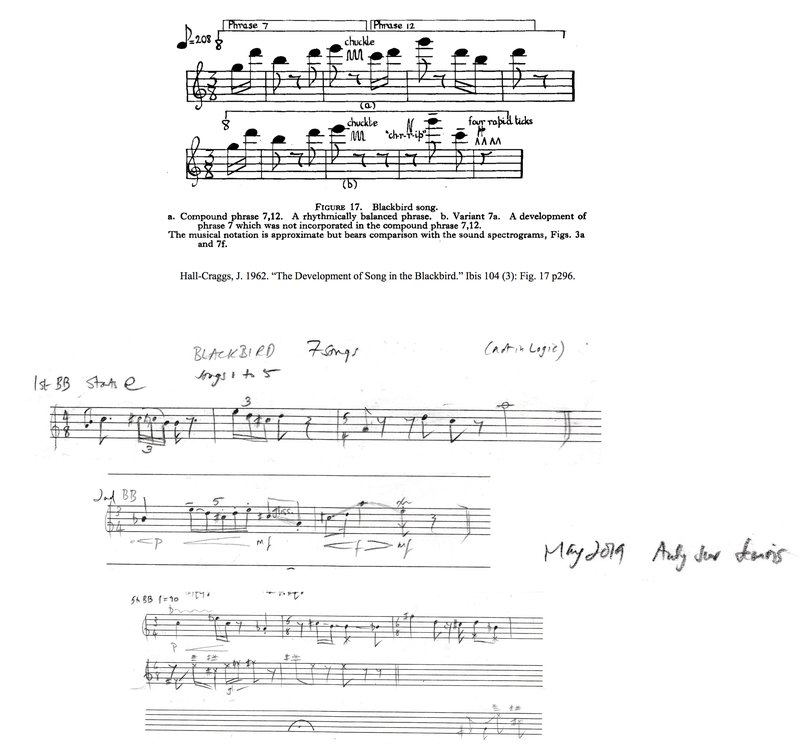

Birdsong is naturally orchestrated, following a set sequence, becoming increasingly diverse the earlier the curtain rises. Blackbird (Turdus merula) often solos first, amid an amorphous chorus, encroaching slowly from the distant east.

Photograph by Malene Thyssen

Photograph by Malene Thyssen

As the experiment progresses, I sometimes dare to join in – very little – on my baroque violin The baroque violin is useful because of its scratchy sound, with strings of twisted animal sinew – sheep’s gut. I want to trace around the sound with the violin or my voice, attempting to highlight each new sound as it enters, and composing tiny sound maps to try and work out what is going on. I entwine my human music with the birds’ by recording both.

It is astonishing how – just around the corner – the balance of the bird orchestra is completely different. I want to see what happens, musically, when I mix the same recording from various locations, so my ears can fly around.

Most birds at Auby perch at the same spot, with the odd newcomer turning up each day. The church bell (cast in 1875 by the Causard-Slégers foundry) starts at 5.45 a.m. – a single stroke and then, at 6 a.m., its long Angelus ring making a sonic grid over which to hear the birdsong. The musical discontinuity of the birds contrasts with the tolling pulse (which then fades), making the birdsong phrases, or song bursts, more understandable than before.

As the dawns develop, the birdsong becomes increasingly dense to my humble human ears. reminding me of how impenetrable an orchestra sounded when, as a child, I was planted as a violin scraper at the back of the second violins. Then, one dawn, I notice a gentle transition back to the sparseness of the early spring, and with it, greater clarity. The orchestration follows that same sequence, the difference being in diversity. The key soloist is still Blackbird – and others, as well as I, have happily remarked upon how virtuosic and joyful the song has been this year. Here is a blackbird again, one of the last remaining as I write on this dim summer dawn, now returned to Brussels.

I envisage birdsong as a way to learn music, training the ear to judge less and listen more. When I listen to those same dawn songs a year later, even at bird-speed, I can hear music that was hidden from me before. I am hearing at a higher resolution. By listening intently to another song while singing my own (or waiting to sing), I touch – however lightly – on how (black)birds listen. I notice what they are listening for, and how this affects what they sing.

Birdsong is an age-old resource for composers, and it also remains an important novelty. These composers of the air are kindred to us human composers. When our ears are attuned to the birds' listening, Their soundtope, "a place in which sound is intentionally structured by different bird species". we embody, however simplistically, hints about organising our little world 'like nature’, but on a human scale. This feels magical because our ears delve into a soundworld which is tough and tantalising to fathom, yet is undoubtedly musical — if we don’t hear bird-song as music, we nonetheless hear it as song. Listening to this makes us quiet, blending in to better experience nature — and composing with it as a creative core can heighten our awareness of birdsong, and our need to protect it.

This year I had great trouble making up my mind where to go for the autumn moon-viewing. Finally, after much perplexed head-scratching, I decided on the Ishiyama Temple. The day before the full moon, however, I read in the paper that there would be loudspeakers in the woods at Ishiyama to regale the moon-viewing guests with phonograph recordings of the Moonlight Sonata. I cancelled my plans immediately. Loudspeakers were bad enough, but if it could be assumed that they would set the tone, then there would surely be floodlights too strung all over the mountain.

A desire to hear birdsong might lead us to consider how to reduce the intrusion of background music in cafés and restaurants, in green or other public spaces, on public transport, from wireless speakers strapped to hikers pulsing through the forest, or even higher decibels wafting over noisy construction sites.

My music reaches out to raise awareness of the right to silence, so that we can listen to each other, have the space to think, hear nature, the trees, and the birds. Here we stand a fighting chance of making uplifting connections with the natural world, because we realise that we are so much part of it.

A bird song can even, for a moment, make the whole world into a sky within us, because we feel that the bird does not distinguish between its heart and the world’s.

🍂

Further reading & references