Hygienically Sealed

Learning to read containment's adaptations: how quarantine drifts from crisis intervention to consumer routine, creating flexible boundaries we mistake for freedom.

This text retrospectively maps patterns first intuited during a COVID-era encounter with a suddenly sinister water filter. Initial material collection and sensemaking via a dedicated Are.na channel followed connections across pandemic apparatuses and pneumatic architecture. Additional inflatables resources curated by Cocky Eek via FoAM’s libarynth. Both collections inspired this arrangement.

In plastic’s sterile embrace, “Hygienically sealed” promises safety. Yet boundaries breathe, membranes flex, as bubbles

—soap and social—

dance on the edge of bursting.

From quarantine to clean room, redoubt to cocoon,

we craft our fortresses, seeking shelter

from a world

that seeps through every seal

More than a literal purification, quarantine forced each traveler to confront him or herself as a foreign body. Quarantine looked different depending on where it was experienced. A small hut or an open piece of fenced-in grass could have been your quarantine quarters in freezing Galatz (on the Ottoman-Russian frontier), or a drafty, stone-floored room in Malta’s huge lazaretto, or a cabin on a ship docked off a coast in a specially marked quarantine harbor, yellow flag flying from the rigging. Passengers on a ship about to dock at a quarantine port would not have known whether to expect lenient treatment or a rigorous smoking of their clothes and bodies and a prolonged detention. Alex Chase-Levenson, The Yellow Flag (2020)

Temporal shock: March 2020 was the moment when centuries of containment technology became personally embodied for millions, suddenly and all at once. When every surface becomes suspect, state-mediated isolation meets a mundane consumer text. Isolation Training Why must a water filter be “hygienically sealed”? Why does thing meant to purify need its own purification? Because the kitchen is where the most intimate biopolitics operate – where we incorporate the outside world through consumption. The kitchen is the domestic frontier between pure/impure, safe/dangerous. Every sealed package, every expiration date, every "sell by" performing the same boundary work as a maritime quarantine flag.

Containers in the kitchen included sauce bottles, salt and pepper shakers, pots and pans, vases, sinks, dish-rack, cups, glasses, bowls … Then there were apparatus with specialized container functions for heating or preserving foods, like an electric kettle, the oven, the microwave, and the refrigerator, with its own set of containers inside. Some containers are strategically inefficient: sieves, colanders, sink drain covers, paper coffee filters. Zoë Sofia, “Container Technologies” (2000)

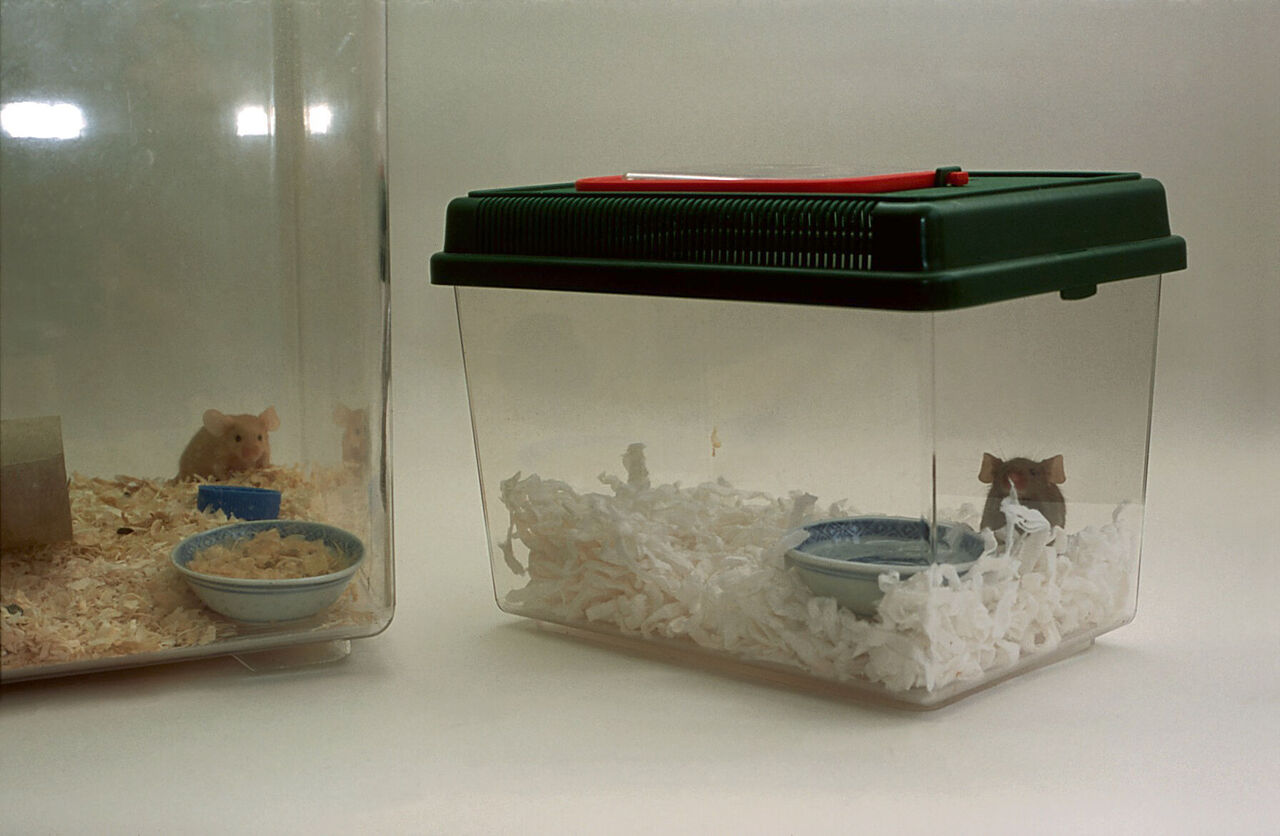

Image by Caroline Gunn, CC-BY 4.0

Image by Caroline Gunn, CC-BY 4.0

When things and people are placed within containers, immediate contact with them is limited. Containers are usually not straightforwardly open to the world: they are often highly disconnected from their local environment. Access to containers is episodic and controlled. Physical proximity, in other words, never implies accessibility. The history of containment, then, is also a history of doors, gates, lids, seals, and locks. Access to resources is mediated by containers and technologies of sealing. Chris Otter, “Container Ontologies”, in Containment: Holding, Filtering, Leaking (2024)

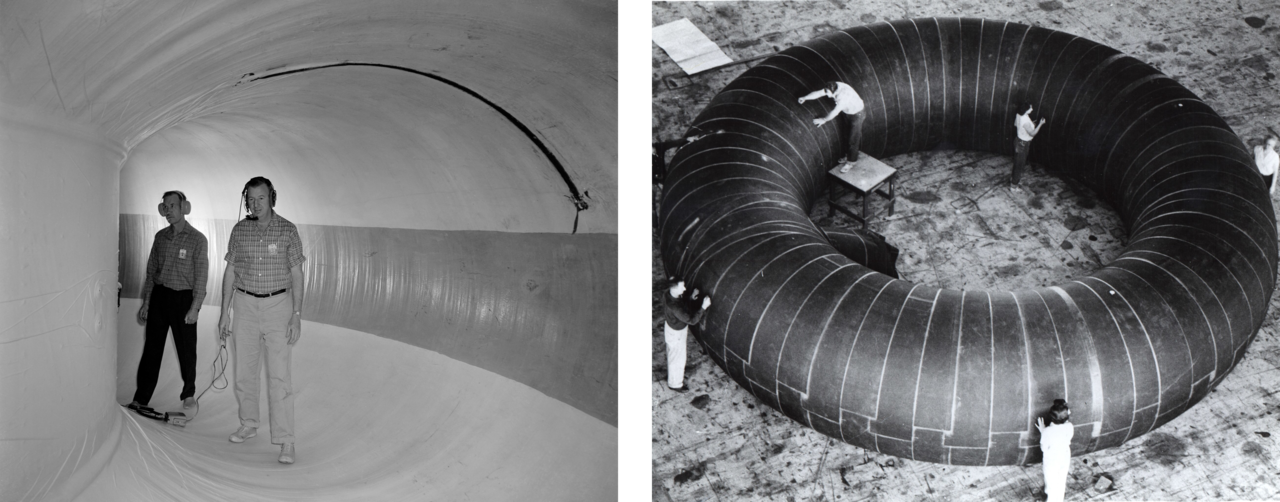

When Goodyear Aircraft Corporation partnered with NASA to develop inflatable space habitats, the conceptual leap from tire manufacturing to atmospheric architecture revealed containing air pressure in a tire and containing a liveable atmosphere in space were variations on the same technical problem. This shelved experiment in expandable habitats traced a direct line from automotive rubber production to what seemed like the most extreme containment challenges imaginable.

Work on disaster control and emergency planning has, over the past years, produced a wide range of pneumatic appliances and applications such as fabddams [inflatable flood barriers], dracones [massive inflatable fuel bladders towed by ships], vehicular hover-pads and GEMs or hovercraft. However, such uses of air structures have not yet been seen as a method of reducing the dependence of emergency planning. That is, they have not been viewed as a potential asset to society enabling rapid yet variable control and communication to be achieved. Such realisation, backed by increasing design and development work, can enable air structures to contribute to a higher degree of sensitivity in society's continuous control of the physical environment. Cedric Price, “Pneumatics: A Key to Variable Hybrid Structuring” (1971)

Notice how Cedric Price's 1971 specifications for “rapid yet variable control” map precisely onto pandemic protocols: quick deployment, controlled atmosphere, temporary yet indefinite duration. Perhaps pneumatic architecture was always disaster response in drag.

So, more than a substance, plastic is the very idea of its infinite transformation; as its everyday name indicates, it is ubiquity made visible. And it is this, in fact. which makes it a miraculous substance: a miracle is always a sudden transformation of nature. Plastic remains impregnated throughout with this wonder: it is less a thing than the trace of a movement. Roland Barthes, Mythologies (1957)

The air-conditioning systems return valves have been closed in public buildings; the fresh air mode is used to optimize indoor air quality. A whole new crowd of nonhumans related to the new hygiene measures has invaded offices, shops, libraries, and the leisure and hospitality spaces: antibacterial cleaning products in toilets and in public service areas, hand sanitizers, wipe stations are made available to clean your keyboard or study space before you begin work in the library or the office building. Albena Yaneva, Architecture After Covid (2023)

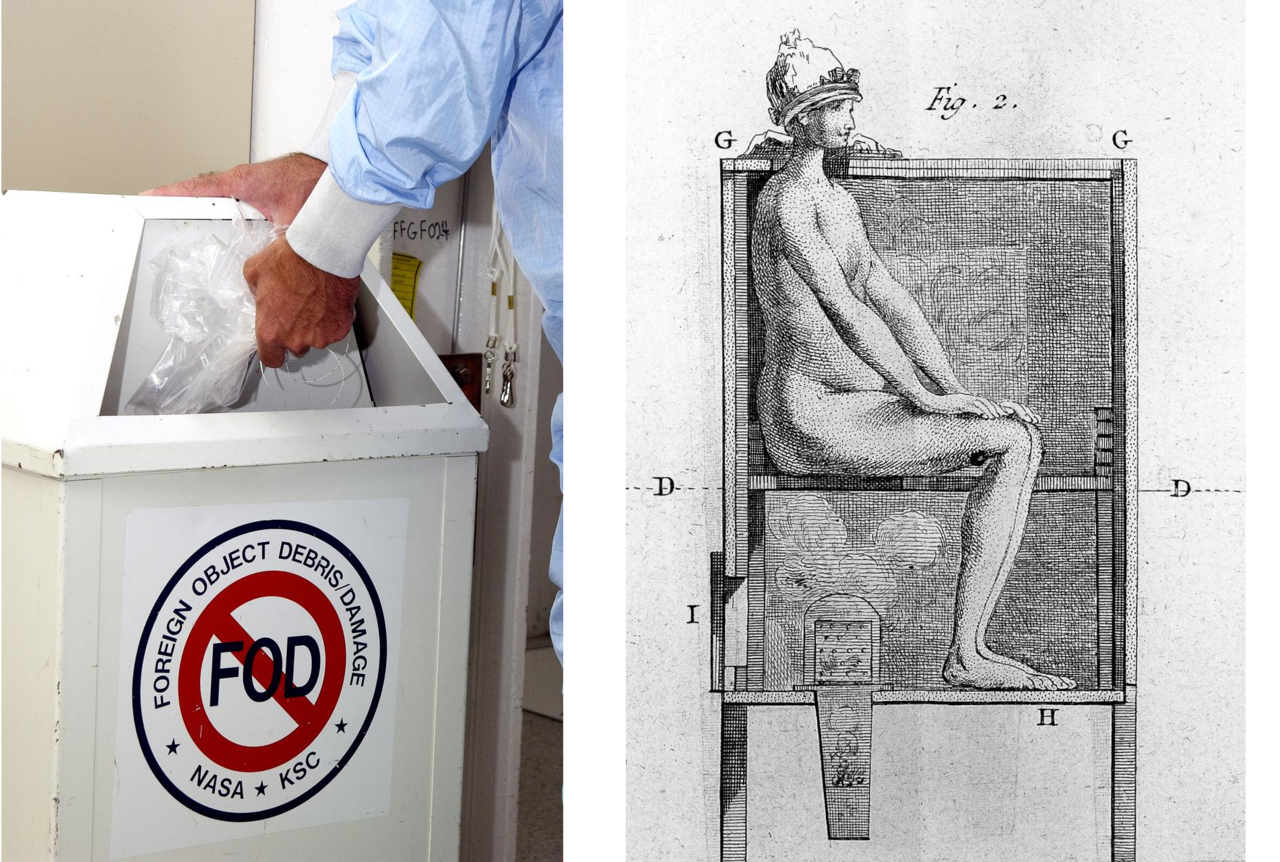

The new apparatus consisted of one or more force-blowing machines... connected with a furnace for generating sulphurous acid gas. By the action of the blowing machines, air charged with the disinfectant was forced through flexible pipes into every compartment of the vessel until it was filled with a saturated atmosphere. The entire apparatus was to be placed on a small steam tug, which would then be moved alongside the vessel requiring disinfection. The air forced into one part of the hold was hence diffused everywhere, and penetrated every crack and crevice by virtue of its elasticity and diffusiveness. Lukas Engelmann & Christos Lynteris, Sulphuric Utopias: A History of Maritime Fumigation (2019)

Filling every crack and crevice with controlled air, 19th-century emergency intervention became 20th-century routine infrastructure, its visible apparatus absorbed into the backstage systems of environmental management.

In the basement catacombs of a mid-century-built corporation sat the heart, or better yet the brain, of the building-machine: the central control console of the HVAC, the automatic heating, ventilating, and air conditioning. From the lobby to the shoeshine stand to the typewriter pool, the ducts and fans of the central control console delivered their standardized environment. Michelle Murphy, Sick Building Syndrome and the Problem of Uncertainty (2006)

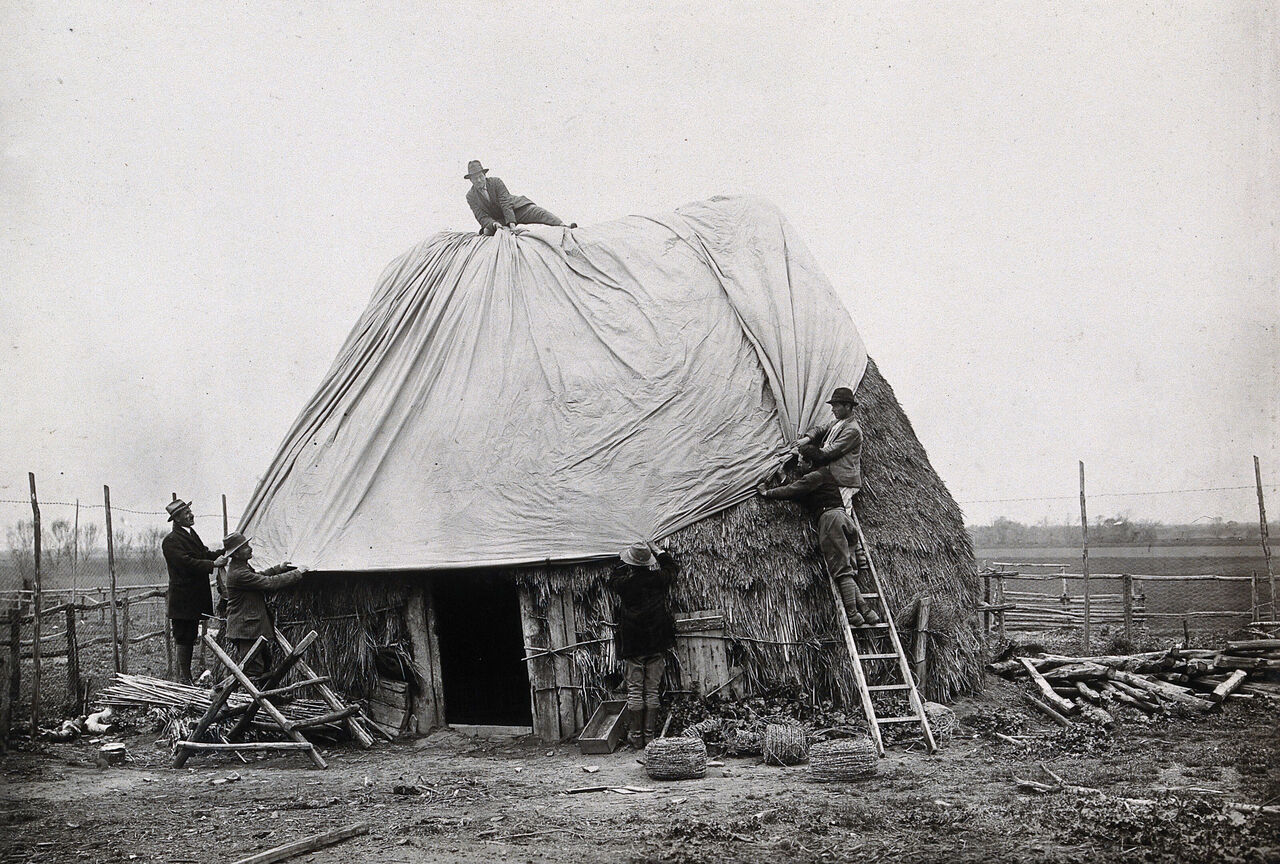

Traditional shelter enhanced with modern membranes; not replaced but upgraded, the logic of atmospheric control adapting to the familiar silhouettes of existing cultural forms.

I was standing up to my chest-hair in water, making home movies (I get that NASA kick from taking expensive hardware into hostile environments) at the campus beach at Southern Illinois. … From where I stood, I could see not only immensely elaborate family barbecues and picnics in progress on the sterilized sand, but also, through and above the trees, the basketry interlaces of one of Buckminster Fuller’s experimental domes. And it hit me then, that if dirty old Nature could be kept under the proper degree of control (sex let in, streptococci taken out) by other means, the United States would be happy to dispense with architecture and building altogether. Reyner Banham, “A Home is Not a House” (1965)

In lieu of columns, beams, and a roof, Banham and Dallegret’s bubble offered a paradigm shift whereby a barely-there membrane could provide all of the structural and environmental properties of a hut. Here, the bubble subverts the hut as an architectural ideal – a “new nature” defined through the deployment of contemporary materials and mechanical systems. Although not necessarily a solution, the pneumatic emerged in the 1960s as an archetype for architectural experimentation. Whitney Moon, “Environmental Wind-Baggery” (2014)

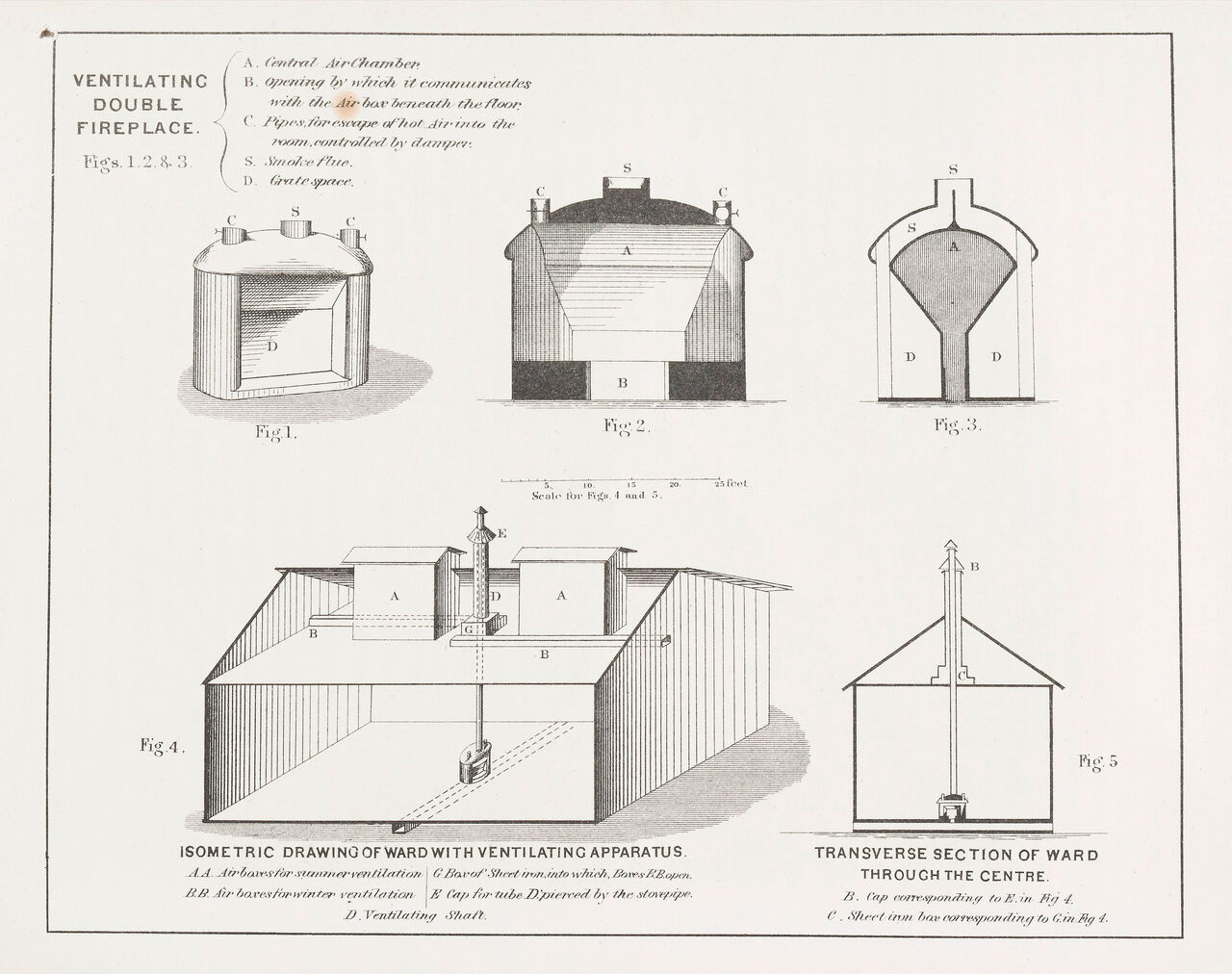

Technical diagrams like this one rendered atmospheric control mobile – schematic solutions that could be implemented across different institutional contexts. Where air quality had once been tacit craft knowledge, it now became systematic engineering. Codified, shared, reproduced. The diagram reveals normally hidden atmospheric apparatus, making visible the mechanical systems that produce controlled environments.

Technical diagrams like this one rendered atmospheric control mobile – schematic solutions that could be implemented across different institutional contexts. Where air quality had once been tacit craft knowledge, it now became systematic engineering. Codified, shared, reproduced. The diagram reveals normally hidden atmospheric apparatus, making visible the mechanical systems that produce controlled environments.

Bubbles offer us a transparency, yet diffracted light distorts what is see in/through bubble layers. The bubble can create a particular border politics that gets internalized, if not checked and curtailed. … The bubble limits, even if it protects. But luckily bubbles are temporary, they burst! The bubble is good in the short term, bad for the long term, but … it is temporary. It pops. It thus compels us to create a world that we can live in, beyond the bubble. Nayantara Sheoran Appleton, “The Bubble: A New Medical and Public Health Vocabulary For COVID-19 Times” (2020)

The new architectures of protection hastily installed across our built environments aim to keep us safe... making the COVID-19 world inhabitable through minimally invasive, barely visible intrusions into our familiar terrains. … These anti-glare barriers allow us to look right through to a seemingly familiar quotidian, denying the need for long-haul adaptation. They’re a temporary accommodation, like an umbrella, to be put away when the sun comes out again. Shannon Mattern, “Purity and Security” (2020)

Both pneumatic bubbles and plexiglass promise to maintain visual connection while enforcing separation. What does it mean that our containment technologies are (so often) see-through?

The bulk of those who performed quarantine did so onboard ship (in most cases because they were sailors rather than paying passengers). Such individuals, more than anyone else, recognized quarantine’s most famous sign: the yellow flag. This was the generally agreed signal, from the late eighteenth century on, that a ship was in isolation. It was, as one ship’s captain mournfully noted, “a public signal that we were tabooed.” Alex Chase-Levenson, The Yellow Flag (2020)

Heterotopias always presuppose a system of opening and closing that both isolates them and makes them penetrable. In general, the heterotopic site is not freely accessible like a public place. Either the entry is compulsory, as in the case of entering a barracks or a prison, or else the individual has to submit to rites and purifications. To get in one must have a certain permission and make certain gestures. Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces” (1967)

Material boundaries embody contradictory promises of protection and imprisonment, freedom and control. The ship's yellow flag becomes the filter's expiration date – signals of containment masquerading as safety. But the ship never docked. We’re still aboard that quarantined vessel, suspended between departure and arrival. The flag still flies – now printed on packages, encoded in expiration dates and our domestic routines. These pliable boundaries work because they feel temporary, adaptive, responsive to circumstance. They bend without breaking. Suspension itself becomes infrastructure.

The strangest thing, perhaps, is not how long it took to learn to see what had always been labelled, but how completely we learned to inhabit the suspended time these labels create. Every sealed package holds us in that harbour, in that moment of indefinite preparation. The containment never ends – it just becomes so flexible we mistake it for freedom.

Further Reading

🜛