Cities Clad in Green

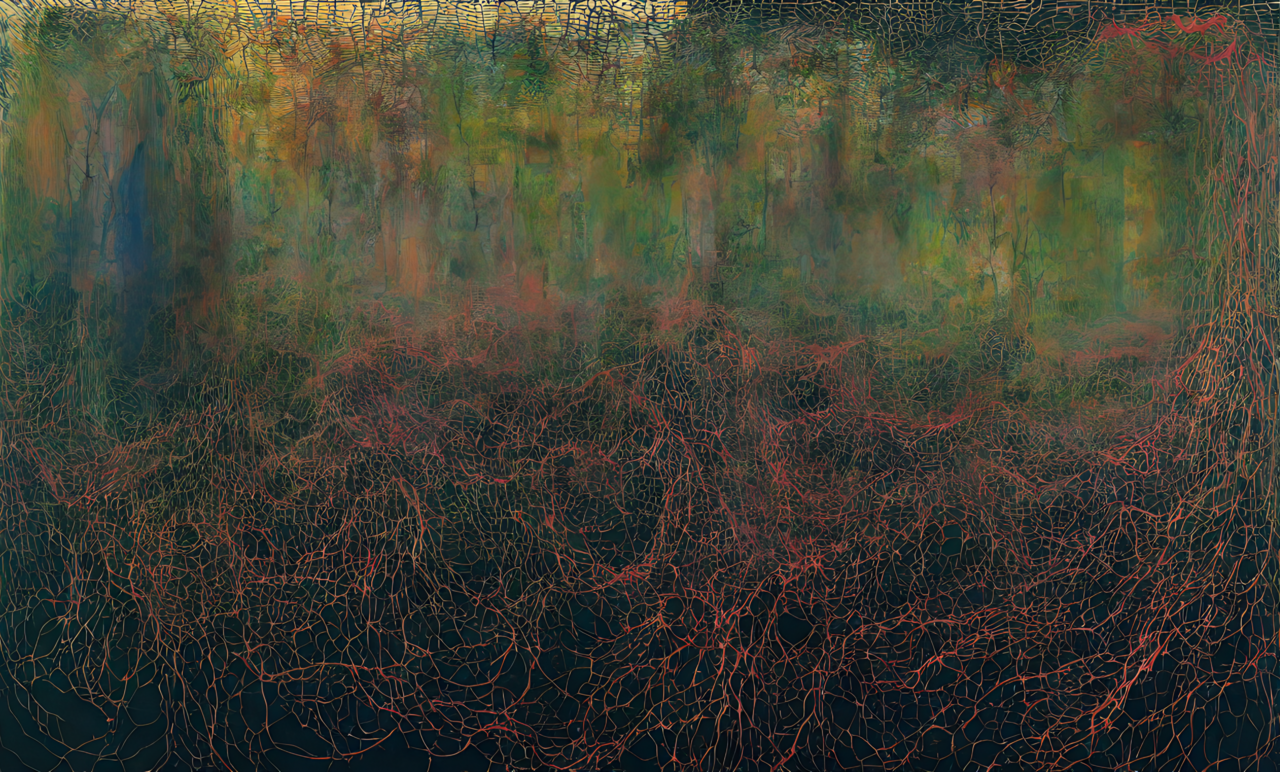

In which the contributors offer impressions of Urban Gardening writ large. A slow accretion of words and images, as lookouts with views across gardens at the scale of cities. Germinating, growing, overgrown.

Photos by the contributors, words gleaned from their readings.

A crack in the pavement is all a plant needs to put down roots. An old-fashioned lamp-standard makes as good a nesting box for a tit as any hollow oak. Provided it is not actually contaminated there is scarcely a nook or cranny anywhere which does not provide the right living conditions for some plant or creature.

Richard Mabey, The Unofficial Countryside

By tracing or uncovering urban nature through relations, urban nature can become pluralized and socialized and include the agency of nonhumans and the vibrancy of matter. [...] What does a given array of social arrangements in-and-through urban natures tell us about the city in question, its people, country, region, and place in the world?

Henrik Ernstson and Sverker Sörlin, Grounding Urban Natures: Histories and Futures of Urban Ecologies

There is one timeless way of building. [...] It is a process through which the order of a building or a town grows out directly from the inner nature of the people, and the animals, and plants, and matter which are in it. […] Without the help of architects or planners, if you are working in the timeless way, a town will grow under your hands, as steady as the flowers in your garden.

Christopher Alexander, The Timeless Way of Building

No way was clear, no light unbroken, in the forest. Into wind, water, sunlight, starlight, there always entered leaf and branch, bole and root, the shadowy, the complex. Little paths ran under the branches, around the boles, over the roots; they did not go straight, but yielded to every obstacle, devious as nerves. The ground was not dry and solid but damp and rather springy, product of the collaboration of living things with the long, elaborate death of leaves and trees; and from that rich graveyard grew ninety-foot trees, and tiny mushrooms that sprouted in circles half an inch across.

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Word for World is Forest

The dispersed patterning of harvestable resources was mirrored in the settlement patterns of tropical cities such as those of the ancient Maya [...]. Dwelling compounds were interspersed with blue-green infrastructure—household gardens, farm fields, orchards, reservoirs, and canals forming both intensive and extensive agro-urban landscapes.

Vernon L Scarborough and Christian Isendahl, Distributed urban network systems in the tropical archaeological record

In the language of forestry and forest ecology, the ‘understorey’ is the name given to the life that exists between the forest floor and the tree canopy: the fungi, mosses, lichens, bushes and saplings that thrive and compete in this mid-zone. Metaphorically, though, the ‘understorey’ is also the sum of the entangled, ever-growing narratives, histories, ideas and words that interweave to give a wood or forest its diverse life in culture."

Robert Macfarlane, Underland, A Deep Time Journey

In the soft apocalypse at Angkor, we can see directly what happens when political instability meets climate catastrophe. It looks chillingly similar to what cities are enduring in the contemporary world.

Annalee Newitz, Four Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban Age

Parks, wilderness, wasteland—each is streaked by social character, by ways of knowing and valuing nature that vary with the city’s sharp hierarchies and shifting alliances.

Amita Baviskar, Urban Nature and Its Publics: Shades of Green in the Remaking of Delhi

The city sits directly above it, on the ocean. There’s nothing visible around it: no land for farming, no hills to break tsunami. No harbor or moorings for boats. Just… buildings. Trees and some other plants, of varieties I’ve never seen elsewhere, gone wild but not a forest—sculpted into the city, sort of. I don’t know what to call that.

N.K. Jemisin, The Broken Earth Trilogy

The timeless character of buildings is as much a part of nature as the character of rivers, trees, hills, flames, and stars. Each class of phenomena in nature has its own characteristic morphology. Stars have their character; oceans have their character; rivers have their character; mountains have their character; forests have theirs; trees, flowers, insects, all have theirs. And when buildings are made properly, and true to all the forces in them, then they too will always have their own specific character created by the timeless way. It is the physical embodiment, in towns and buildings, of the quality without a name.

Christopher Alexander, The Timeless Way of Building

The catalogue of forms is endless: until every shape has found its city, new cities will continue to born. When the forms exhaust their variety and come apart, the end of cities begins.

Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

Often liminal spaces suspended between rural and urban, nature and society, they are a gathering place for marginalised human communities and practices as much as they are for endangered nonhuman species.

Jonathon Turnbull, The Kyiv thickets

The silver mirrors the perturbations of topography and the forest here—the same way it does everywhere. Yet the silver here is brighter, somehow, and it seems to flow more readily from plant to plant and rock to rock. These blend to become larger, dazzling flows that all run together like streams, until the ruin sits within a pool of glimmering, churning light.

N.K. Jemisin, The Broken Earth Trilogy

New pedestrian routes are being developed among the roof gardens which spread throughout the city. Linked to one another by lightweight footbridges, they allow people to stroll through a space in which their view is not blocked by the built-up fronts of the buildings which face onto the streets – where they can see the sky and the horizon, as well as the cityscape of the roofs and gardens.

Anne-Catherine Labrique in Luc Schuiten's Vegetal City

The term ruderal comes from rudus, the Latin term for rubble. [...] Ruderal ecologies grow in the inhospitable environments created by war and exclusion; they emerge by chance and entail illegal border crossings—often unnoticed in ethnographies of a city that tend to focus on people, buildings, institutions, or infrastructure.

Bettina Stoetzer, Ruderal Ecologies: Rethinking Nature, Migration, and the Urban Landscape in Berlin

Our sense of planet is not a cosmopolitan rush but rather the uncanny feeling that there are all kinds of places at all kinds of scale: dinner table, house, street, neighborhood, Earth, biosphere, ecosystem, city, bioregion, country, tectonic plate. Moreover and perhaps more significantly: bird's nest, beaver's dam, spider web, whale migration pathway, wolf territory, bacterial microbiome. And these places, as in the concept of spacetime, are inextricably bound up.

Timothy Morton, Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence

Sometimes I wish I could photosynthesize so that just by being, just by shimmering at the meadow's edge or floating lazily on a pond, I could be doing the work of the world while standing silent in the sun.Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass

❧

Further Reading & references can be found in the bibliography.