Having been there

Some notes on fieldwork, as a situated, experiential way of learning; with visual impressions from fieldwork conducted across the FoAM network and some lessons learned.

As The Crows Fly, Kumano Kodo, Japan, 2018. Photo by Nik Gaffney

As The Crows Fly, Kumano Kodo, Japan, 2018. Photo by Nik Gaffney

Did you ever go on a school field trip? Did you venture beyond the classroom with your peers, travelling somewhere to learn something new, receiving information from the people and places you encountered? Did you put on headphones broadcasting sounds or narration, or lean in to a guide or speaker, as they recounted unfamiliar (hi)stories, conversations? Probing the complex relationships between your studies and the world around you, were you able to touch, smell and taste, lost in your topics of interest? A situated, experiential form of learning, usually brief and intensive, field study invites students to get to know a specific place in its many, varied dimensions.

Fieldwork is about learning in, from and with a field, rather than learning about the field at a distance (as you might from a book). It entails the use of direct, labour-intensive, and often low-tech methods, contingent on physical presence – rather than theoretical, desk, or online research. In fieldwork, abstract data gains additional dimensions through exposure to original sources and the situation in question. We may think and act differently in the presence of other people or beings, traversing living biomes, floating in a river, or being battered by a sandstorm.

Legal Identity for Trees, Belgium, 2012. Photo by Rasa Alksnyte

Legal Identity for Trees, Belgium, 2012. Photo by Rasa Alksnyte

If there is a heaven, and I am allowed entrance, I will ask for no more than an endless living world to walk through and explore. —E.O. Wilson In Canfield, Michael R., ed. Field Notes on Science & Nature. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2011.

The ends of fieldwork can be as varied as those who participate: from filling gaps in knowledge or solving mysteries, gathering inputs for a creative process, to seeking direct contact with one's objects of inquiry. But while much varies, fieldwork shares some common features across domains. It typically requires putting in the legwork to gather evidence, making first-hand observations and talking to people. It involves working with imperfect data, collected in real-life circumstances. This material can often only be gathered in the field, and the research process is usually iterative, looping between identifying evidence, hypothesis-formation, and following leads.

Mongoose 2000, Uganda, 2015. Photo by FoAM Kernow

Mongoose 2000, Uganda, 2015. Photo by FoAM Kernow

A lot of talk about fieldwork comes from the natural sciences, geography, and colonial adventuring expeditions. While we share the value and epistemological authority of having been there, there are other fieldwork lineages that are worth attending to. Alternative approaches might adopt practices and approaches modelled after those used in epidemiology and public health, sociology, investigative journalism and beat reporting, criminal detective work, psychogeography and place-writing, design, and the arts.

Dust & Shadow, California, 2019. Photo by Maja Kuzmanović

Dust & Shadow, California, 2019. Photo by Maja Kuzmanović

A field research mindset, according to Jan Chipchase, emphasises curiosity, empathy, listening, humility, open-mindedness, spatial awareness, lateral thinking, and an ability to hustle. paraphrased from Chipchase, J. (2017) The Field Study Handbook, Second Ed., San Francisco and Tokyo: Field Institute, 2017. This mindset is not exclusive to any one domain.

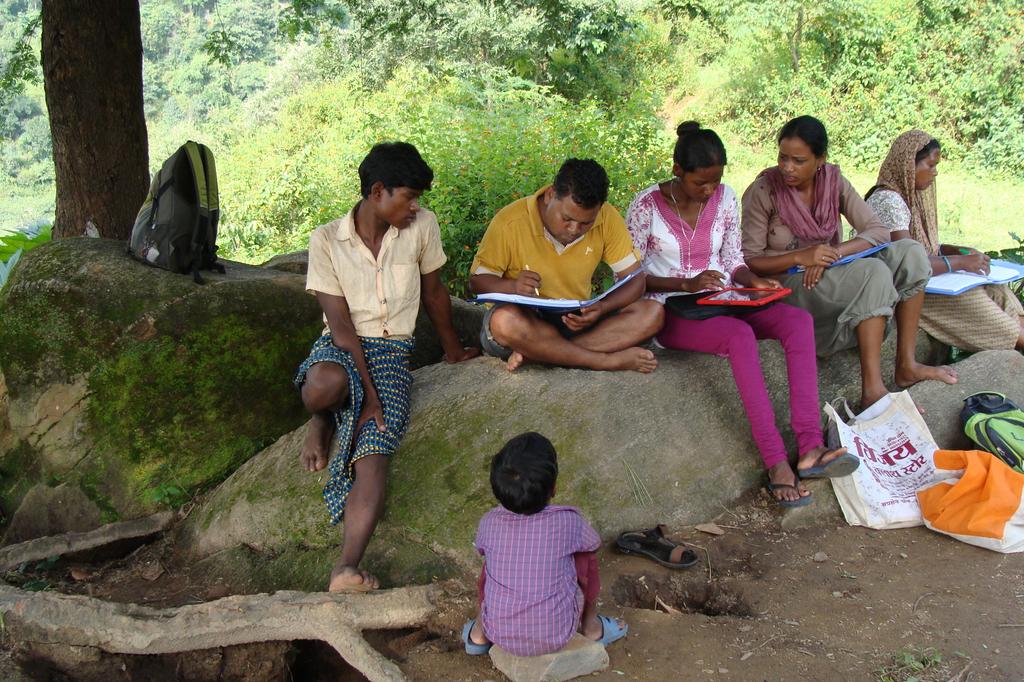

Mongoose 2000, India, 2014. Photo by FoAM Kernow

Mongoose 2000, India, 2014. Photo by FoAM Kernow

Knowing, in the sense of knowing a friend

Arboreal Identity Workshop, Belgium, 2012. Photo by Rasa Alksnyte

Arboreal Identity Workshop, Belgium, 2012. Photo by Rasa Alksnyte

Spectres In Change, Finland, 2019. Photo by Nik Gaffney

Spectres In Change, Finland, 2019. Photo by Nik Gaffney

Who is the expert in fieldwork? Expertise might not belong to a person, but a shared condition of knowing, emerging from interactions between all of those involved. Researchers contribute the tools and techniques of fieldwork, which may differ depending on their background and training. Local guides (human or otherwise) offer intimate knowledge of the area, acquired through lived experience. The expertise offered by fieldwork, then, is knowing in the sense of knowing a friend. Knowing that cannot – and should not – be owned. Knowing in fieldwork becomes a commitment to the field. Shifting the locus of attention from extracting knowledge, field researchers should be encouraged to not just think about what they need from the people and places in their fieldwork, but also about how they can reciprocate. There may even be no prior goal set for fieldwork, letting an area speak through us, to see what comes up.

Dust & Shadow, Arizona, 2018. Photo by Nik Gaffney

Dust & Shadow, Arizona, 2018. Photo by Nik Gaffney

Working in the field raises complex questions regarding the ethical dimensions and implications of working in relation to contested sites, sites of extraction and the climate crisis. These are sites brimming with hidden tensions, complex histories and unstable futures. —Bridget Crone, Sam Nightingale & Polly Stanton In Onomatopee 225. Fieldwork for Future Ecologies: Radical Practice for Art and Art-based Research

Towards reciprocity between the field and the fieldwork

- Ask permission Make sure you are welcome before entering.

- Pay attention Listen, be with the people and places without prejudice. Tune in.

- See with fresh eyes Share your insights (if asked); your outsider perspective may be appreciated.

- Spread the word Translate gathered impressions into stories that can circulate further (if appropriate).

- Heal and repair Use data and physical evidence from the field to improve its conditions (if appropriate).

- Leave no (unwanted) trace Walk lightly, without causing damage or disturbance.

- Make an offering, give a gift Create something (an object, experience, ritual) to express your gratitude.

I Listened to Everything, Very Carefully

❧

Further Reading & references can be found in the bibliography.