Being Rural

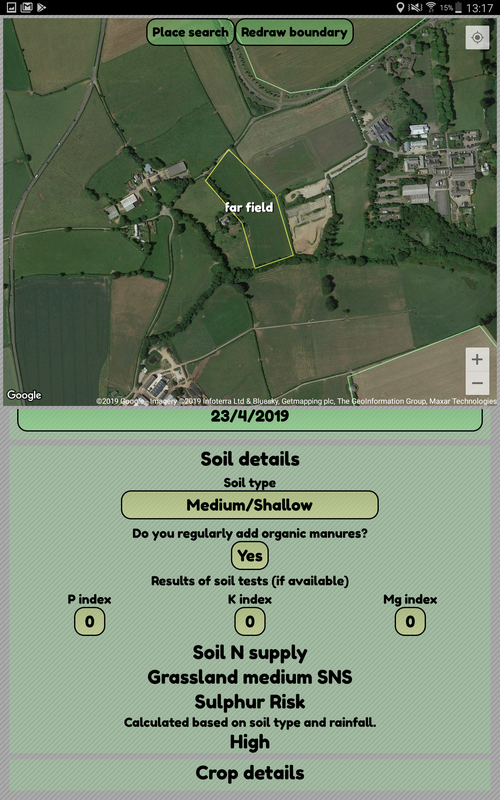

The co-founder of Then Try This discusses redistributing power around farming with natural fertilizers and bringing farmers and regulators into conversation with one another via the Farm Crap App project.

Excerpts from Recovering Experts

Maya: Did you guys come up with the Farm Crap App trying to meet a specific need; was it something that grew out of various experiments? Could you tell me a little bit about its origin story as, like, a practical entity that’s also creative?

Dave: Yeah, so, that’s an example of something where somebody came to us with something that they wanted. And that was this amazing college in Cornwall, called Duchy College, and they have an incredible history. They come out of, I think it was after the Second World War, when there was rationing, and food was really hard to come by. They have all these experimental agricultural fields where they’ll be constantly running different experiments and trying out different seeds and different methods of cultivation and things like that. But they also train farmers as well. So they’re training up young farmers and some of them go on to be researchers and some of them will have their own farms. I think a world expert in micro-propagation is based there, growing things from tiny fragments of plants, really rare things. So really that project is as much about them really understanding farmers and what they need but also their humor and how to talk to them, which is very different from a lot of academic, or a lot of research sort of things where they very much see themselves as a separate field to “the public.”

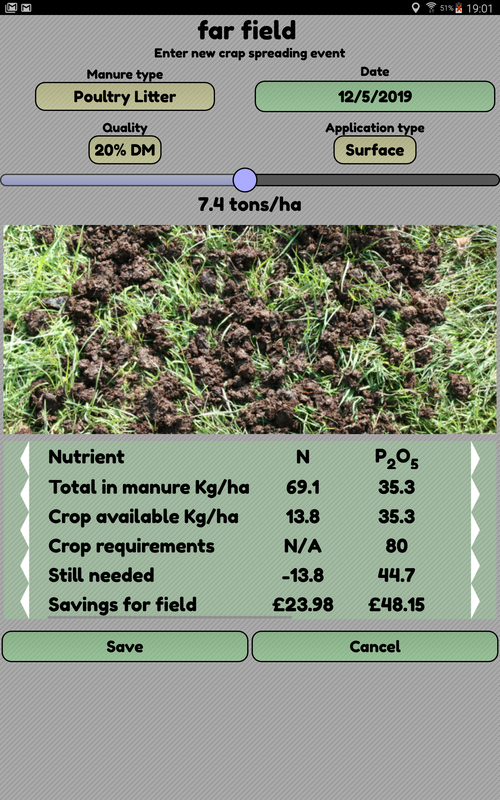

The problem that’s being solved there is to get the farmers using natural fertilizers. And the reason that they don’t is because of the regulations. They have to report what they spread on their farms, and if an inspector comes along and they’ve put too much on they can be fined for that. So to avoid putting too much on, it’s much safer to buy bags of fertilizer that come from petrochemical industry because they have the numbers written on the side. And you feel much more comfortable that you’re not going to get fined.

The thing with that for us has been really understanding that setup, the fact that you’ll have farmers that own the farms, who have the contractors that do the work, you’ll have the landowners, so often the farmers will be renting it from the landowners, and then you’ll have the regulators, then you’ll have a whole industry of people contracted to do soil testing. And learning where we fit within that, and where we’re sort of taking power away from one group and giving it to another group, that’s been a kind of real learning process, lots of workshops and actually just getting farmers and unions and regulators all in the same room has been amazing, because you just get them talking, and then you can’t stop them! You give them something to work on together, to kind of draw out the relationship and things, and suddenly they’re just — we had to push them all out to have lunch at one point.

It’s a really lonely profession, that’s the other thing that people don’t realize. They have the highest rates of depression and suicide and things like that. It’s not really the cozy life that we like to think.

So I think with the farming it was very much that we just have to listen really carefully to what the people we were working with, what the researchers are telling us, it is much more a commission-based thing where we do what we’re told. But, having said that, there is a way that we approach it because we’re based in a rural place, and we’re hundreds of miles away from the nearest built-up kind of city. Being rural ourselves immediately gives us an ability to kind of do that work.

❧