Hip Deep in the Thick Present

In which the author uses the tools of science fiction and social theory to explore infrastructural reconfigurations for Anthropocene futures.

Excerpts from a series of blogposts published on FoAM’s website.

The “thick present” cannot be summarised in linear narrative, because the thick present is not linear.

How about this: the world in which you live—which is contiguous with the planet on which you live, but which is not commensurable with it—is a four-dimensional event space with around eight billion simultaneous narrative points of view running in parallel. And that’s if we only count the humans.

Perhaps the only truly graspable thing is the ungraspability of the world. Narrative doesn’t scale — though this is not a shortcoming of narrative, and might be better thought of as its saving grace. Nonetheless, so much of the challenge facing us is rooted in the impossibility of narrating systemic agency and causality. No one is to blame, but everyone’s complicit.

Fragments of a Hologram Rose: Everything Everywhere All At Once

Infrastructure is the medium of the media. Media are the user interface of infrastructure. Your view on the consequences of your consumption is curated by a vast system in a state of advanced autopoesis. You choose what you see, but you choose from a menu whose options are determined by profitability.

The Effacement of Consequences

Sure, putting solar panels on every surface might help get us away from an energy system whose countless hydra-heads are still slurping at oil-wells and gas platforms and coal mines.

But the rare earth metals required for their manufacture, and for the manufacture of the ever-more ubiquitous electronics that will be needed to manage their generative capacity—not to mention the lithium for all the rechargeable batteries that everyone’s personal electric vehicle, be it a scooter or a Tesla, will be built around—whose land will they be dug up from? Who will profit from their extraction and refinement and manufacture and shipping? Who will make them, what will they be paid, and what injuries will they receive in the process? Who will be able to afford them, and who will not?

The Unbearable Lightness of Solarpunk

Simply stating that unfairness exists and that we are its benefactors achieves nothing, beyond the superficial assuagement of a guilt that would be far better alchemised into an anger, and burned as fuel for the real work.

What’s the real work, you ask? I’m still working that out—and the answer that fits my situation and skills will not be the same one that fits yours. Working out what the work is is part of the work. Maybe it’s even the hardest part of it; that would explain the lively market in off-the-rack answers.

And hey, if you find one that fits, good for you! But don’t then turn evangelist. You wanna highlight a particular problem in the world? Great, go for it; that’s one aspect of the work, if you’re called to it. But if you find yourself wanting to advocate for one particular solution, then check yourself. This planet’s got enough salesmen already.

The Thick Present / The Thin Ice

Think inside the box.

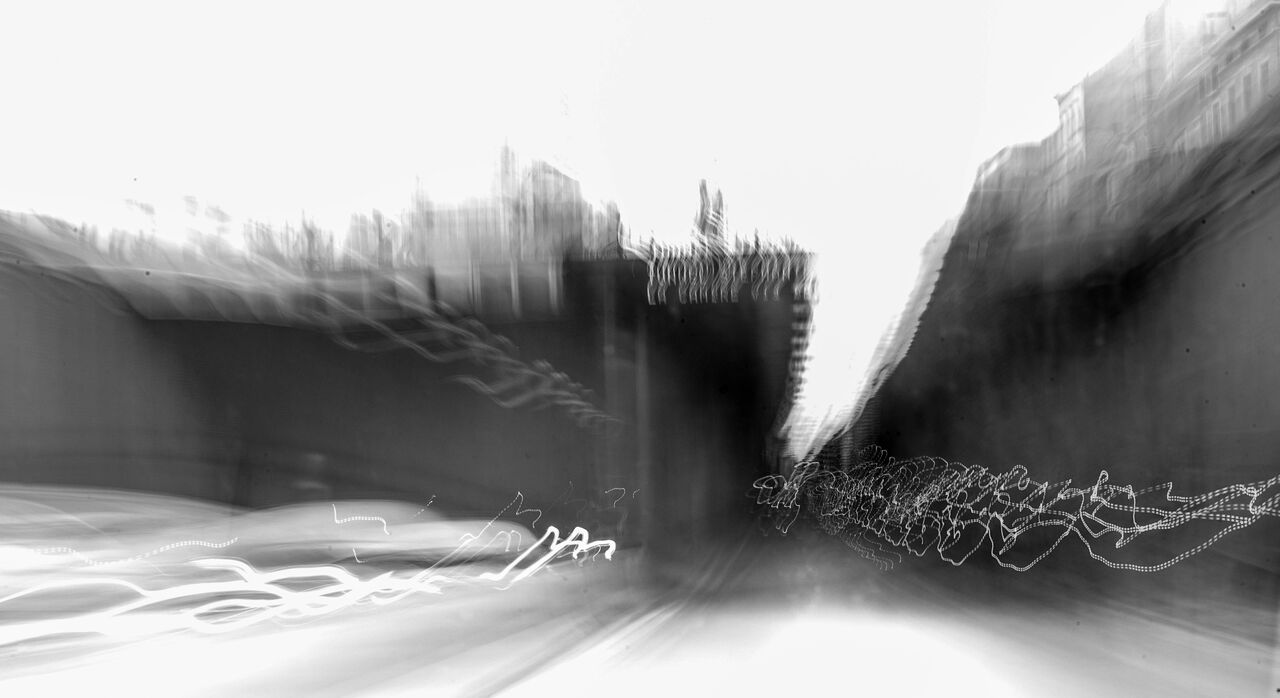

We were once promised that the internet would be the end of geography. But where you are in “meatspace” still matters a great deal, even when it comes to receiving packets of information rather than packets of commodity goods. The network has edges, margins.

The last mile never stops being the last mile. The last mile is the ultimate bottleneck.

Nothing is connected to everything, but everything is connected to something.

Donna Haraway

Outside of glassmaking, to talk of a bottleneck is to talk of the point in a system where bandwidth—the capacity of traffic which can be reliably passed through that point—is restricted. Think of the motorway turn-off to a busy location on a bank holiday weekend. Think of the Suez Canal.

The particular supply-chain disruptions caused by the Ever Given accident were for most people lost among all the other supply-chain disruptions ongoing during the pandemic. The ship’s name is a glorious irony, if we see it as a metonym for a system which, for most of us, has been exactly ever-giving, existing only to fulfil the desires which other parts of the same system have worked so hard to encourage us to have.

Quite early on in Spook Country, the middle book of William Gibson’s Bigend trilogy, a secondary character—a curator of geolocative art—notes that “cyberspace has everted”.

Spook Country was published in 2007, when the idea of ordinary people having access to GPS-enabled technologies was still moderately shock-of-the-new. The novel, and the rest of the trilogy, wrestles with what was at that time the imminent spatialisation of “cyberspace”, which now feels like a fait accompli long since passed. Also in the frame are the relationships between marketing and (artificial) scarcity, origin stories, military history, economics, precarity, hideous wealth, art, the collector’s impulse, deep states and global logistics.

At the time, it felt like a stretch to claim that a novel whose plot depended on the movement of a mysterious shipping container would have much to say about life in the subsequent decade or so, though a number of people claimed it anyway. The claim, and the novel, and the trilogy, hold up alarmingly well.

Pattern Recognition / Spook Country / Zero History

The immaterial is perhaps the most material thing there is right now. Ask yourself why you never see it.

The Materiality of the Immaterial

🝓