Does It Scale?

A preoccupation with scale permeates the contemporary market economy; what other mechanisms might produce the conditions for meaningful change?

The scale question

Imagine. You are standing around, talking about somebody’s business or livelihood endeavour For the purpose of this text, we circle between terms of “business”, “venture”, “project”, and “livelihood endeavour”, and take up an expansive definition of “enterprise” proposed by activist lawyer Janelle Orsi as“any productive activity that could bring us sustenance”. (perhaps your own). Maybe you are experiencing this undertaking first-hand, noting its material details, its undeniable existence as a fact on the ground, and the intricate relationships within which it operates. Then someone asks, “So, does it scale?” It is a potent question, that snakes through our understanding of business, bringing with it a snarl of things to be unravelled.

Scale is the lingua franca and the bugbear of business. For the non-conventional business practitioner, the question — “Does it scale?” — is a persistent refrain, voiced by parents, funders, business advisors, and party guests. It can be a covert means of expressing scepticism, or, stated sincerely, enfold a set of expectations that merit further scrutiny. That bigger would be better goes without saying: “scale” is code for scaling up.

A preoccupation with scale permeates the contemporary market economy, where a focus on output, financial profits, and economic growth goes largely unquestioned, in everything from corporate business strategy to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals SDG 8: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all. Scale also underscores arguments that the market economy is inherently unsustainable, in critiques levelled by ecological economics Daly, “A further critique of growth economics” and the degrowth movement Latouche, Degrowth Economics, which challenge the plausibility of unbridled (or even “sustainable”) economic expansion. A focus on scale pits those who advocate for small-scale, local initiatives Illich, Tools for Conviviality; Schumacher, Small is Beautiful against those who see these as irrelevant, utopian-nostalgic forms, unable to meet the magnitude of the problem: a voracious “grow or die” capitalist system. Scharzer, No Local: Why Small-Scale Alternatives Won't Change the World

These discussions reflect a blurring between scale as size (small to large), scale as level or reach (local to global), and scale as growth (scale as a verb) — meanings that are not synonymous, but can have overlapping effects. For feminist economic geographer J.K. Gibson-Graham, “questions of scale are usually another way of broaching power”, where only the large and the global are assigned consequence as sites of meaningful change. For those of us working to build livelihoods beyond the confines of a competitive market economy, “Does it scale?” might be the wrong question, but its recurrence demands a response — one that might shake out some of its assumptions and yield questions that are more generative.

“Does it scale?” is a question that has long been asked of Feral Trade, and it is from behind the counter of that uncommon business that I learned to formulate my own reply. Feral Trade is a grocery business, art endeavour, and long-range economic experiment, trading coffee, olive oil, and other vital goods outside commercial systems. All the suppliers and all of the customers are gleaned through social connections. Goods are dispatched in the spare baggage space of friends, colleagues, and passing acquaintances travelling on other business — art, cultural, commuter, vacation, and diasporic. As a social protocol run over time, on an ad hoc basis, and with no tangible assets other than a shared web server, Feral Trade materialises an underground freight network that is at least as robust and reliable as Fedex or DHL.

I started Feral Trade in 2003, six months before Facebook. As such, the business embodies a substantially different response to the emergent potential of computer-formed social networks than the big stories of platform capitalism, the Amazons and Ubers. The connections Feral Trade runs on are commercially inefficient. These sociable, occasional relations of collaboration, acquaintanceship, and passing encounter do not scale up, or maximise utility, as an efficiency-focused business model would demand. Instead, the business behaves like an organism, for whom relentless growth would be like cancer.

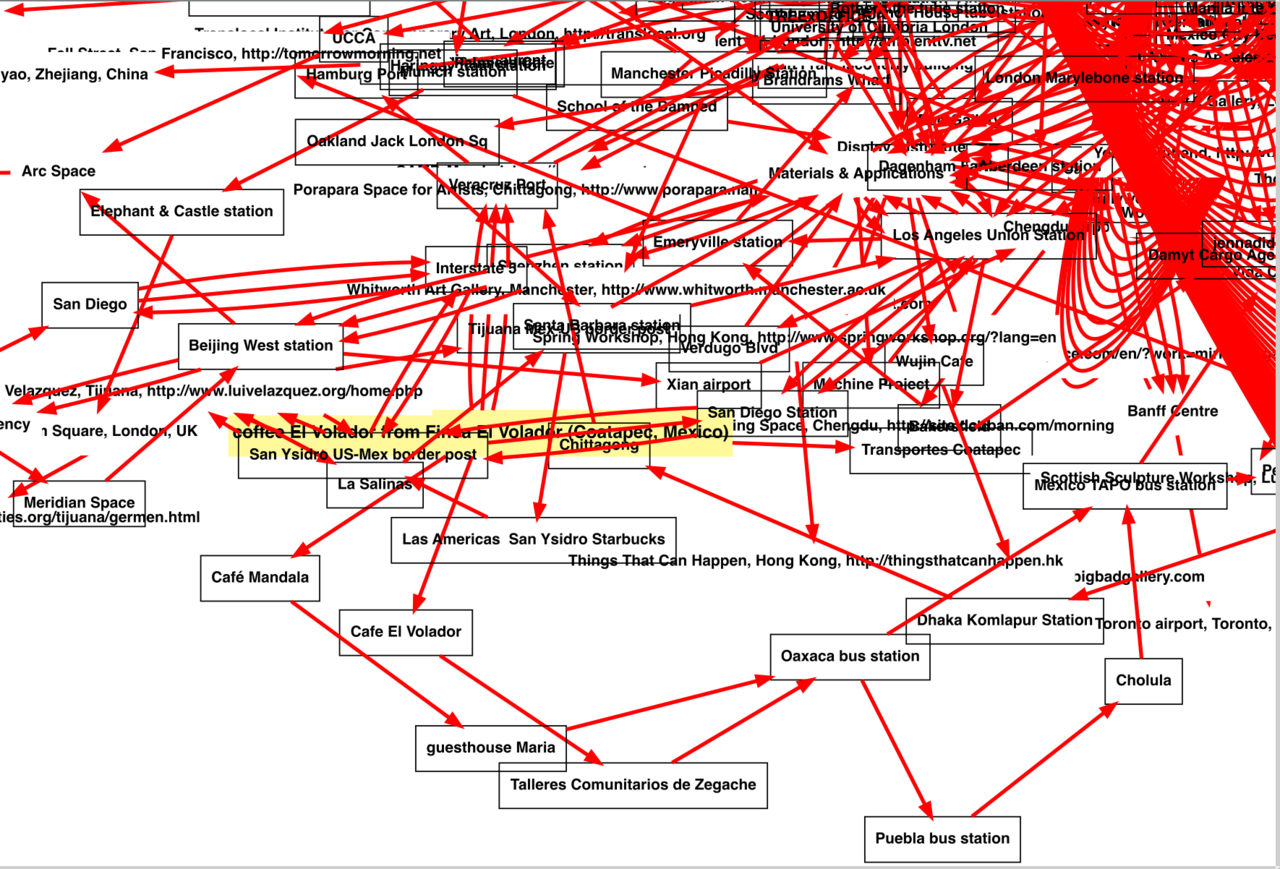

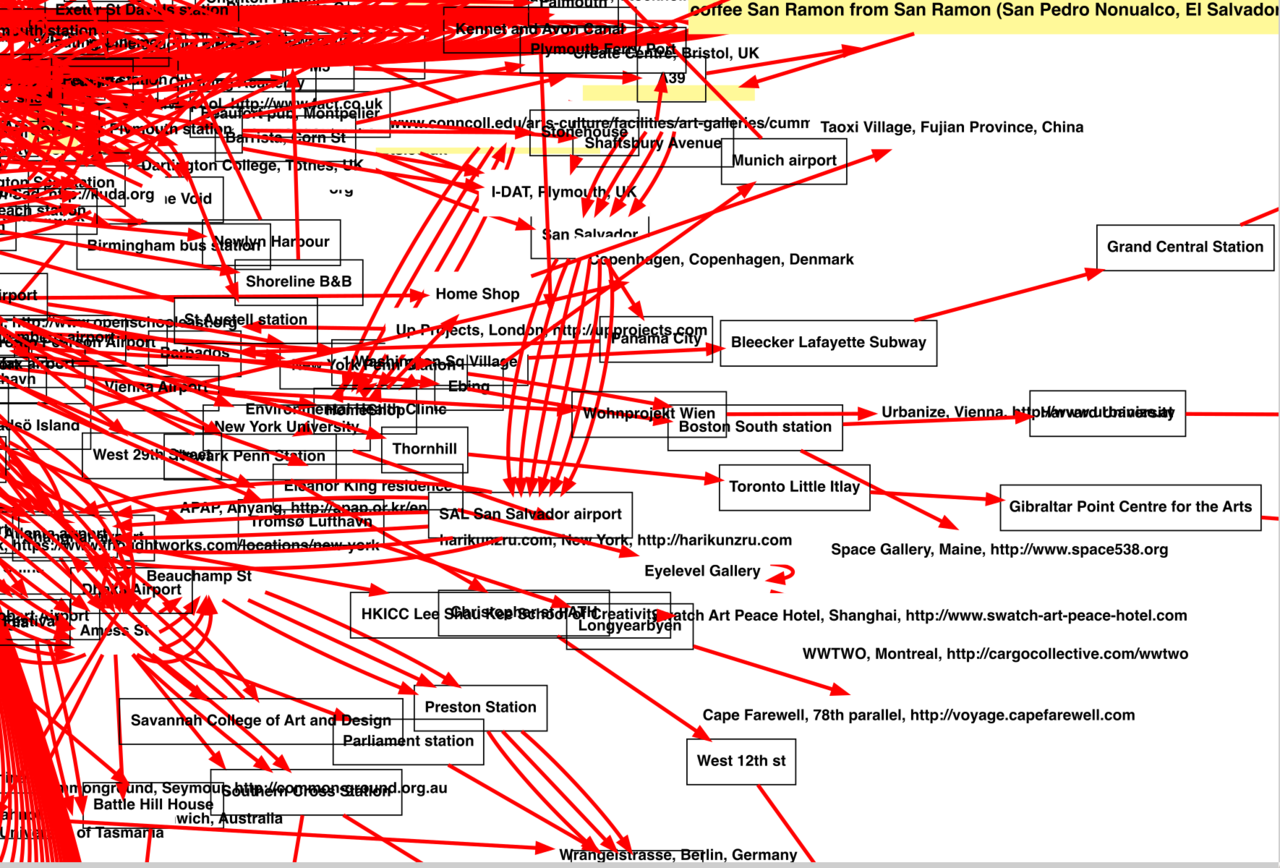

The network maps that Feral Trade generates The Feral Trade Courier website serves as an inventory, display case, content management system, and shipping archive for groceries. present a portrait of a business as a haze of relations that do not expand in size, but increase (or thicken) their connections — in knowledge, depth and intensity—over time. The maps show human-to-human relations meshing with those with other entities — products, organisations, offices, homes, airports, and rail hubs. It is a portrait of an enterprise in or as its ecosystem, unravelling the schematic of a network into something more indeterminate and unbound.

Feral Trade coffee network map. Rather than the promise of transparency, the maps become ever more effusively illegible over time, as deliveries layer up

Feral Trade coffee network map. Rather than the promise of transparency, the maps become ever more effusively illegible over time, as deliveries layer up

Some theories of scale

In her essay“On Nonscalability”, anthropologist Anna Tsing hones in on a fixation with scale in Western thought, tracing its origins to the workings of European colonial plantations, reliant on forced segregation and modularisation of labour, materials and investment. In Tsing’s summary: “exterminate local people and plants; prepare now-empty, unclaimed land; and bring in exotic and isolated labor and crops for production”.

Anna Tsing,“On Nonscalability” Rather than argue the case for small or large scale practices, Tsing focuses on the mechanisms of scaling — the practices and qualities that enable a project, whether a business enterprise, a research undertaking, or the “world-making” activity of economic development, to expand without changing what it does. For Tsing, scalability is not a precondition for meaningful change but its opposite. While associated with progress (a powerful form of validation), a scalable design can only succeed by suppressing the transformational diversity of social relationships – those moments of encounter across difference, where project elements interact in unexpected ways, that could change the outcome of the whole project.

In geography, scholars have long challenged preconceptions of scale, highlighting its contingency as a socially-constructed phenomenon rather than a preordained category. Moore, “Rethinking scale as a geographical category: from analysis to practice” Scale is used as a marker of political agency, fixing things in hierarchies where small forms “look up” to large ones, or the edges look to the centre. One proposal is to do away with the geometry of scale altogether, for a flat ontology that locates actions and things in complex, emergent webs of relations, rather than those determined by level or size.

Another approach that disorders and disassembles ideas of scale can be found in sociologist John Law’s concept of the “baroque”: a way of thinking without overview. A baroque perspective refuses to conflate size with importance. It looks “down” into detail of local instances, concentrating on the specific and the heterogeneous, rather than “up” for the global picture. From a baroque standpoint, size is a specific accomplishment — the attribute of a particular endeavour — not a value in itself.

However, one does not need to go deep into these theoretical discussions to realise that their application for the business operator on the ground are limited. When put on the spot by the“Does it scale?” question, calling in “nonscalability”, “flat ontologies”, or “the baroque” is not necessarily going to move the conversation with the business advisor or the parental team along. It might be more fruitful to read the question between the lines: what is it trying to say? If scale stands in for power and consequence, but also for viability and security, the ability for a project to communicate its intentions and maintain its existence, there is a pressing need to address these emotional and perceptual dimensions.

Feelings of scale

For Gibson Graham, the fixation on scale is as much an emotional commitment as a rational calculation. Gibson-Graham, Beyond Global vs. Local Our understandings of scale are deeply ingrained in everyday experience and the crystallisation of feelings that accrue to different scales: the “local” as static and authentic, the “global” as dynamic and abstract. Shifting our attention to scale’s emotional dimensions provides an opportunity to turn the question that animates this text around. If scale is a stand-in for power (in business, as elsewhere), what mechanisms other than scale might produce the conditions for meaningful change — or, at least for surviving and thriving?

Other geometries

Gibson-Graham suggests replacing a politics of scale with one of ubiquity. Economic practices considered as local (housework, self-provisioning, intra-family lending) are already everywhere: they are local and global at the same time. Gibson-Graham and Dombroski, “Introduction to the handbook of diverse economies: Inventory as ethical intervention”

Others from inside the business school have challenged the association of scale with success, and of size with possibilities for action: cooperation between small enterprises can also result in large-scale activity. Parker, “Alternative enterprises, local economies, and social justice: Why smaller is still more beautiful” Pearson and Parker, “Is Small Always Beautiful? A Dialogue” And there are substantial economic traditions outside Western knowledge systems that think without scale altogether. Australian Indigenous scholar Tyson Yunkaporta, who belongs to the Apalech Clan in far north Queensland, responds to the concept of economic degrowth with idea of “increase”: growing the complexity and beauty of relations within a system rather than its size.

For me, when I say “scale”, the first thing I think of is the thing that comes off a fish, but that's just me.Tyson Yunkaporta. Green Dreamer, 2020

Pragmatic responses

For living examples of business working differently with scale, consider Premium Cola, a German drinks company who apply an “anti-volume discount” to their product, charging less per unit to smaller customers. When large-scale distributors asked for a volume discount for purchasing more, Premium refused: large-scale distribution comes with a (hidden) environmental cost. Instead their “anti-volume” discount favours smaller buyers, at the same time giving Premium a more stable and resilient structure than if it were to rely on a few large customers for the bulk of its orders. We might also think of the Sail Cargo Alliance, a new assembly of ship owners, cargo brokers, traders, and farmers, working together to reinvent the ancient art of transporting cargo on wind-propelled ships. The sail cargo movement seeks to reduce the scale of the shipping industry by slowing it down, fundamentally changing the equation of what gets shipped and why. These micro-operations will never deliver the aggregate emissions cuts required to meet the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change global transport goals. But they do represent the kind of wholesale rethinking of the business of shipping that change on this scale demands. De Beukelaer, “Tack to the future: Is wind propulsion an ecomodernist or degrowth way to decarbonise maritime cargo transport?”

For Feral Trade, the modus operandi is to wax and wane in response to changes in its wider trading ecosystem and the trader’s current interests. While this business is (decidedly) not a model for anything, it does point to the extra capacity that art might contribute to the question of scale. Artists engage in scales of practice and influence that are largely detached from the bigger-is-better equation. To the extent that scale is part of artistic success, this tends to be in the form of level or reach — with achievements measured through a prominent position in a high-profile exhibition, or one’s own solo show. But intricacy, detail, the minimal, and the irreproducible are also part of art’s currency. As such, artists might prove useful intermediaries for breaking down scalar assumptions — while taking care to not fall prey to the logics of scale ourselves, on the business side.

To start with, we might respond to “Does it scale?” with our own shortlist of questions. What would be an appropriate scale? How does this particular endeavour respond to the emotions and politics that scale introduces? Does the scale of resistance need to match the scale of the problem? Parker et al., Horizons of Possibility And: what else aside from scale might produce effects of consequence?

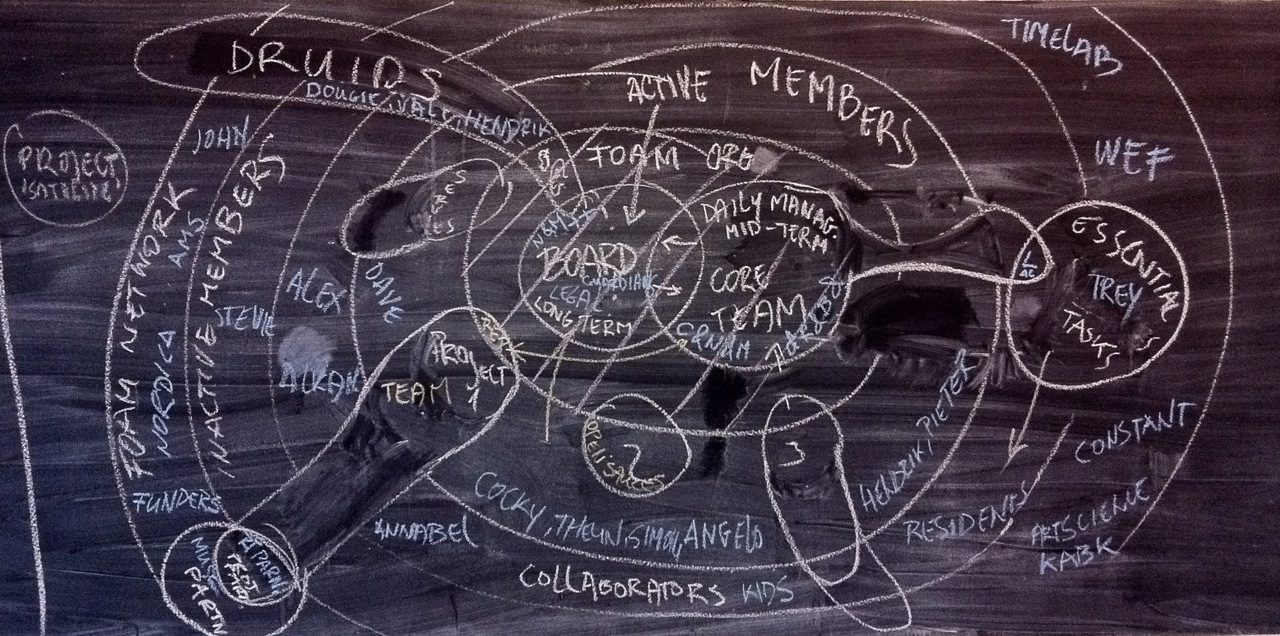

FoAM vzw (Vereniging Zonder Winst, non-profit association in Belgium) was founded as an independent legal entity in the aftermath of its host institute’s bankruptcy, following that institute’s attempts to scale at a rate that proved unsustainable amid the 2001 stock market downturn. Learning from this, scaling “up” was never desirable for us. Instead, we started to scale “sideways” into a trans-local network capable of realising larger projects — including partnering up with individuals and organisations, spawning micro-enterprises, and working across jurisdictional boundaries. A network can change shape depending on external pressures, available resources, and the needs of those involved. Over two decades, FoAM has developed from the connections between people, their tools, the contexts in which they live and work, and their divergent forms of knowledge.

Like an ecosystem, the FoAM network exists in a dynamic equilibrium. Complementary skills, interests, and relationships have proven more significant for FoAM’s continued survival than scale. There has to be just enough overlap and diversity (of interests, skills, personalities). Too much or little of either throws the network off balance, demanding adaptation from the whole and from all of its constituent parts. When network members (natural or legal persons) join, change (size, purpose, activities), or depart, the balance of complementarity and redundancy changes too. This then influences the kinds of projects we can take on, and what products and services we can offer. If we grow too much in one direction, another part of the network will atrophy.

Instead of growing, we talk about cultivation. Working at an appropriate scale requires tending to all the entities involved, including individual people (and their biological and psychological needs), legal entities (and their administrative, financial, and operational peculiarities), the environments they exist in (wider networks of collaborators, landscapes, institutions, and governments), and the needs of the network itself (governance, community building, shared infrastructure). As with a thriving garden, it is not the scale that matters most, but health, diversity, reciprocity, and the network’s life-giving potential.

🝓

Further reading & references