Technology in the Public Interest

On instituting otherwise, with a collective infrastructuring sensibility for radical kinship, elastic solidarities and the reimagination of greyness by means of ordinary glitter, and how that contributes to a resistant public interest for abolishing the cloud regime

TITiPI emerged in March 2020 with a bug report challenging established frameworks for public interest technology. Registered as a non-profit association in Brussels since 2022, and co-directed by Miriyam Aouragh, Seda Gürses, Helen V Pritchard, Jara Rocha and Femke Snelting, TITiPI experiments with instituting otherwise – rethinking how socio-technical practices and technologies might support resistant publics.

This exchange is part of FRICTIONS, Kate Rich’s Marie Skłodowska-Curie Postdoctoral Fellowship at Brave New Alps (IT). The project works with TITiPI, FoAM, and other small-scale cultural initiatives to surface and negotiate the obstacles they encounter, centring everyday administration as an overlooked site for critical collective practice.

Kate Rich: I am dispatched by my colleagues at FoAM to record an interview with The Institute for Technology in the Public Interest (TITiPI) for the Anarchive. It's an area where FoAM's interest in different ways of re/imagining technology crosses with my intrigue around organising otherwise. This assignment is also an opportunity to open up a long-rolling conversation I've been having with Femke Snelting, with other members of the TITiPI collective. I meet Femke, Jara Rocha and Helen Pritchard on a BigBlueButton video call, with three questions from FoAM to get us started.

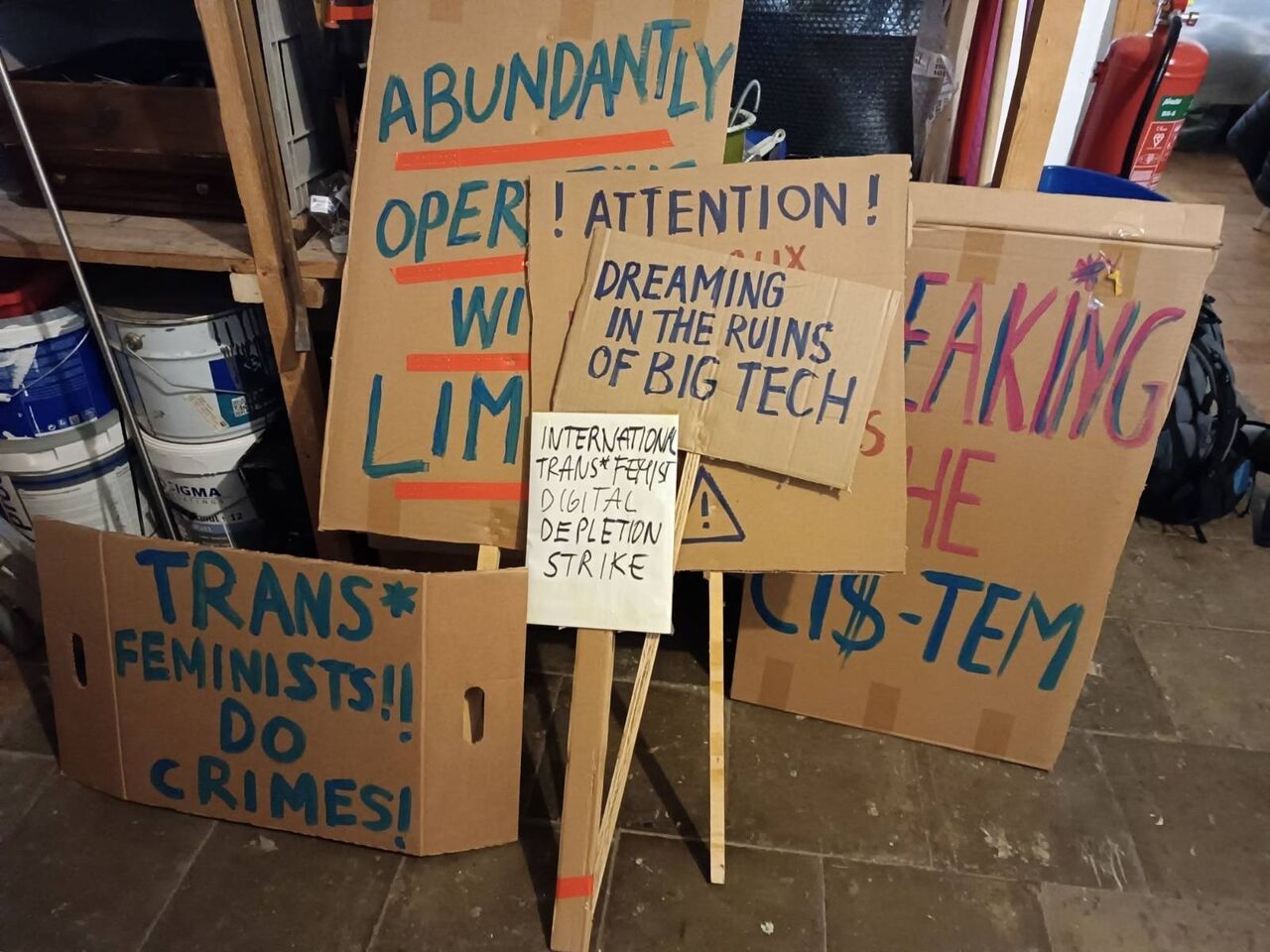

Picket signs for the Trans*feminist Digital Depletion Strike, March 2023.

FoAM: When you started TITiPI, you decided to name the organisation 'Institute for technology in the Public Interest'. What do or did you mean by 'public interest technology'?

{{alt-txt: a set of five brown cardboard banners placed on the floor of an interior room, with colourful handwritten messages in capital letters, reading “trans*feminists! Do crimes!”, “Abundantly operating within limits”, “International Trans*feminist Digital Depletion Strike”, “Dreaming in the ruins of Big Tech”, “Breaking the Cis-tem” and a sixth one of which only the top can be read, calling for “Attention!”

Instituting otherwise

Femke Snelting: TITiPI is interested in instituting as a kind of infrastructuring, especially in the context of the depletion and reconfiguration of institutions that computational infrastructures bring about. It is a time when institutions are crumbling on all levels, from the inside and under outside pressure. This is the landscape in which we started TITiPI. Among many other things, we also experiment with visioning, planning, public commitments, contracts, reports, year plans, budgets, legal conditions – all those time and space operations that institutions usually do and that have now become increasingly cloudified and processed on digital platforms.

Instituting for TITiPI is an attempt to go against an as-a-service approach where everything should be flexible and instantaneous. Instead, we want to structure for collective generosity and exuberance at a time when too many things are on fire. So TITiPI's critique is not anti-institutional but about the need to institute otherwise. It is linked to the particular abolitionist politics we are committed to, which means we need to think about what infrastructures we need to dismantle, as much as which ones we need to build.

Resistant public interest

Helen Pritchard: One of the things I realised after we had taken up the public interest term, is how much Marx actually wrote about cooperation in the public interest. And, specifically, that this articulation of cooperation of public interest is for workers, migrants, queers, and all of the oppressed – not for the elites. So, I think public interest functions in quite a different way in TITiPI than it does, for example, in these huge university or NGO projects, where it's definitely a public interest for racial capitalism. For us, to be able to enter into those spaces by using the name ‘public interest’ is part of resisting the idea that public interest should be serving the Big Tech companies and the richest people in the world. For TITiPI, that is definitely not the public we are interested in cooperating and building for. So what we're working with is not a public interest for everybody, but a kind of resistant public interest.

Radical kinship

FS: The institutional biography of TITiPI on our homepage says that we want to 'activate and re-imagine together what computational technologies in the “public interest” might be when “public interest” is always in-the-making'. The ‘in-the-making’ is super important for us too. To not think of the public as a static category, as civilians within a so-called democratic sphere. This name ‘The Institute for Technology in the Public Interest’ places us somehow between civil society organisations and NGOs, because it seems to resonate with those kinds of institutional practices. But it's really a rethinking of the interfaces where thinking and deciding about what technology is and does can happen – a porous structure that allows conversations between different groups impacted by what technologies can do.

HP: It's also an experiment in how to have a type of instituting that's based in love and emotional connection. Not just to each other, inside TITiPI but to other people who are working with infrastructure. People who are struggling with how research – after so many years of co-optation by Big Tech companies – can actually inform our practices, and at the same time, how to show up when many of us are the target of fascist violence. We are also seeing the institutions that are supposed to care for people becoming super-depleted by their dependence on Big Tech. Can we instead reimagine a kind of infrastructure that is made for radical kinship? What might it mean to have a public interest that is not just the basic thing of barely living, but a project of love and pleasure? I’ve learnt a lot recently from Anna Puigjaner and Ethel Baraona Pohl’s work on housing and care. Puigjaner and Baraona Pohl co-lead the Chair of Architecture and Care at ETH Zürich, researching how housing and urban infrastructure can support care, pleasure, and kinship beyond nuclear-family domesticity. See Puigjaner's Kitchenless City project. Public interest should be about these modes of care, of supporting life, beyond just a basic idea of care – and we shouldn’t shy away from practical solutions either! That's the type of reimagining we're interested in: that the public interest might be that. And then how to do that is really hard!

FoAM: Part of your work seems to be, as you state, 'to reimagine technologies'. How do you actually work on alternative technological futures? What possibilities do you see for 're/imagining technology' in the current context? What does “reimagining technologies” mean for TITiPI?

Reimagining technologies

HP: Reimagining is different to imagining – imagining futures or imagining technologies – the work that the “re-” is doing there is really important. It's different to the mode of imagining alternatives that we've all been involved in, in other collectives or practices.

For TITiPI, reimagining technologies is not only imagining technologies for a life-affirming, flourishing future. It's also working collectively, to understand how technologies are being imagined by the elite, and through the supremacy of the tech industries, who are telling us that their cloud technologies and infrastructures are necessary to support life. Part of the work that TITiPI does is reimagining the material impacts of the technologies proposed by these mega corporations, and that often means anticipating their sinister, anti-earth and anti-life ways. So it's not just a mode of reimagining what's good.

We were talking recently about spell-breaking and spell-making as part of this practice. Spell-breaking these dominant practices and imaginaries, but also making new spells. FoAM: TITiPI's invocation of spell-breaking/spell-making resonates with feminist traditions reclaiming witchcraft as counter-hegemonic practice (see Silvia Federici). For related Anarchive explorations of spell-work as collective enchantment against capitalist inevitability, see In Her Interior’s Hexing the Alien, Cat Jones & Ingrid Vranken’s Spell Kit for Navigating Uncertainty, and Francesca da Rimini’s Vernacular Magic.

Jara Rocha: A framework that really affects the way we work is abolition, that is also itself a research practice. It's not just an interventionist practice into structures, but also a practice of reimagining them, so it has a lot to do with simultaneous doing and undoing. That reimagining happens across space-times including rebellious memories, inventive side-steps or uncomfortable prospections, so it's not only the projection of a future of linear progress, in a developmentist sense. That is one of the fundamental spell-breakings – and it has a lot to do with the importance of remembering, attuning and the archive, like in the work that we did with Miriyam Aouragh, revisiting her work on Palestine Online, or archive visits looking for visual evidence of infrastructural resistance. Both examples ground reimagining in existing resistance archives: Revisiting Palestine Online examines Aouragh's 2012 study of Palestinian digital solidarity networks; Infrastructural Resistance in the Archive convened researchers exploring the International Institute of Social History’s archives for visual evidence of historical infrastructural struggles. Not this fallacy of the from-scratchness of imagination-as-innovation that circulates so widely in technological realms.

Collective infrastructuring

HP: Something else that we've been working on for the last decade is to move from this mode of reimagining technologies to reimagining infrastructures, which looks quite different. The scale and temporality is really different to a lot of the practices we've all been working with in the past, which were more to do with tools or scenographies or situations.

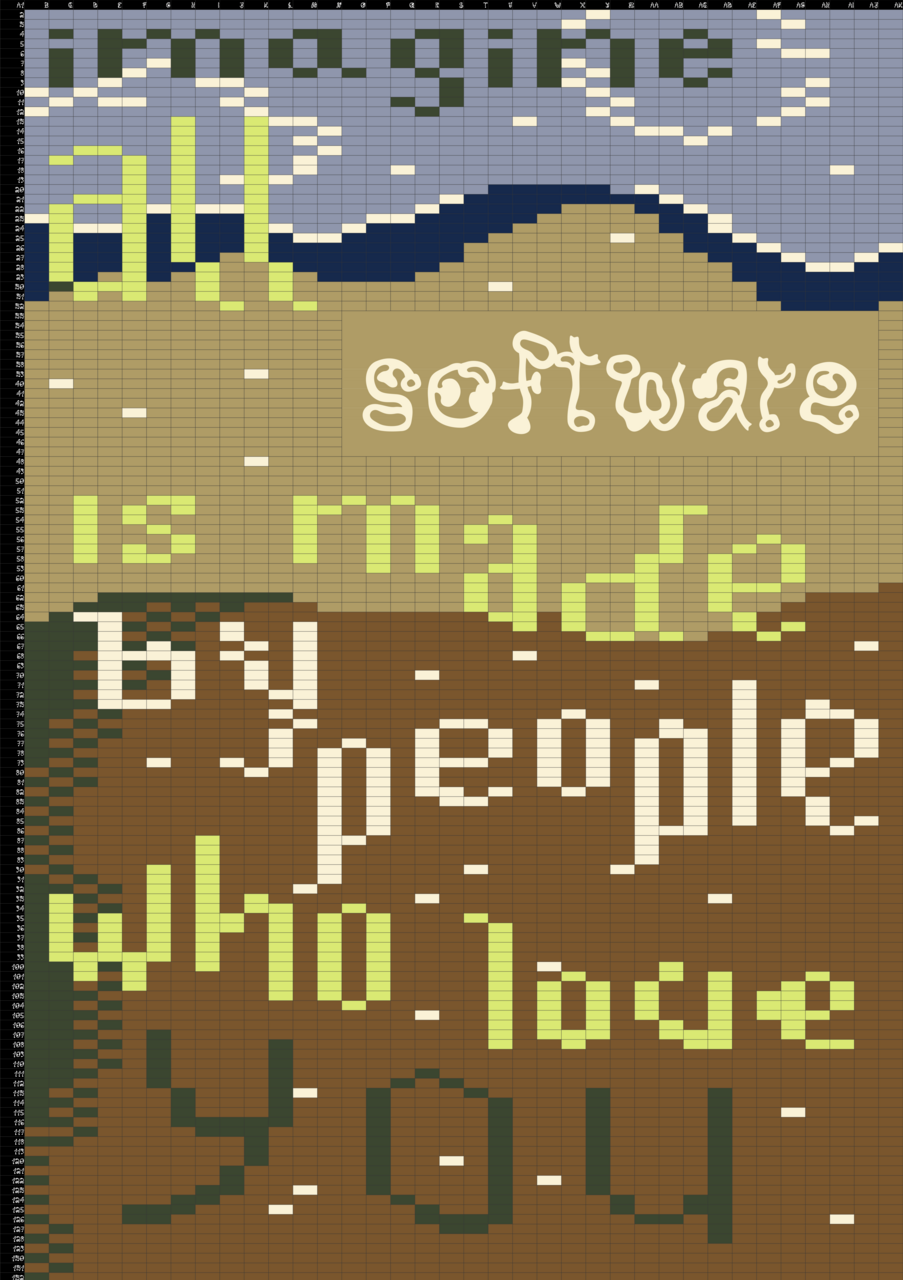

What if all software was made by people who love you? Design: Cristina Cochior and Batool Desouky (2022)

{{alt-txt: A banner with a base of calc sheet structure of which the cells have been colored so they operate as pixels and form a background pattern in brown and blue tonalities; on top of it, in lowercase green and white letters it reads “imagine all software is made by people who love you”; around the text there’s some pixels in white which provide a glittery effect to the composition

One of the slogans in the posters that we made is what if software was made by someone who loves you? – it's one of Seda's favorite phrases, and she has the poster behind her desk. In a way that's how I see the TITiPI project right now. Not what if all software was made by someone that loves you, but what if infrastructures were made for radical kinship? Radical kinship is intergenerational and compassionate, it has a generosity towards other peoples' practices, other types of alternative-making – it's not instantly saying that what other people are doing is wrong.

FS: An important part of it is making situations where we do this reimagining together with other collectives and individuals. What the reimagining looks like is then also dependent on who joins and what they bring to the table. TITiPI's collaborative practice includes co-building the Tech Infrastructure Coalition with Equinox Initiative for Racial Justice (addressing gaps in how civil society and policy engage with AI and digitalisation) and publishing Infrastructural Interactions with sex worker-led project Other Weapons, gathering testimonies on surveillance, biometric verification, and infrastructural violence.

Elastic solidarities

JR: A question we would love to spend more time with, is what forms of academic, para-academic and militant research do we need, to provide the conditions for the kind of elastic solidarities that need to be in place. That idea of elasticity has a lot to do with reimagining, because we cannot afford to have a continuation of the forms of solidarity with limits – as attempted by the left over the past decade – in the face of the authoritarian consolidation we're seeing in front of our eyes. We need elastic solidarities because these infrastructuring practices we are talking about happen in a realm of super thick and hence uneasy dependencies – practices which, in their very functioning, include concerns about how to depart from colonial, extractive and hyper-agile logics.

To think with elasticity helps, as a material description of how solidarity might take place, when that network of dependencies is there. It's elastic in the sense of acknowledging the specific conditions for a solidarity to stay active in a particular moment: sometimes it might need to stay tight, other times it can be loose, but that looseness doesn't mean the solidarity stops. I think that's fundamental, especially with difficult relationships or engagements with other social actors and structures. As Helen says, it's letting go of the narrative of the alternative for an ongoing attempt of considering how solidarity could look, when it's in relation to a very surprising other.

HP: We are not concerned with only being an emergency response unit, because it's clear that the emergencies are continuously there and being intensified all the time. But it's also definitely not the moment to step away from the fight and the resistance that's needed – like yesterday in UK, with trans rights being instantly rolled back into another era overnight. On 16 April 2025, the UK Supreme Court ruled that "woman" and "sex" in equality law refer exclusively to biological sex, not gender identity – excluding trans people from legal recognition and sex-based equality protections. We do need an emergency response, just not in that mode of reaction. That's also a question of elastic solidarities: how to keep going into different spaces of struggle, coming back, going into others, realising that they don't always converge and they're often in friction. What kind of flexibility do we also need to have within TITiPI, to be able to deal with emergencies? And with fascism and racism and anti-queerness and other forms of infrastructural violence.

Grey infrastructures

HP: I think we're all avoiding talking about whether we actually make some technology or tool or infrastructure. There is definitely a resistance in TITiPI to making lots of different, speculative, playful technologies as part of this reimagining. At the same time, making infrastructures for TITiPI to function practically – but also to function practically with skin in the game, with a particular type of ethics and political practice in place – is very important to what TITiPI is.

It's important that the TITiPI email is on the Irational server, and the work that went into it being there, being part of what it means for TITiPI to exist as an instituting infrastructure. These types of infrastructures are super crucial for us, to be both in and adjacent to: it's like the grey infrastructure of reimagining technologies. And it's important for us to have things like the wiki-to-print infrastructure, or to be working together on the wiki, or to consider where the TITiPI server is going to be, or to experiment with a week of radio streaming on a local server – the plurality of those practices and keeping them present. While trying to find ways to resist the type of work that's been really co-opted in creative practice, of flashy, glamorous technological alternatives.

JR: We talk about grey infrastructure, but greyness doesn't mean non-exuberant and non-flamboyant. There's a big collective bet in TITiPI on turning that grey infrastructure-making practice into a life-affirming, engaging, flamboyant, exuberant practice.

HP: That idea of exuberance is also coming out of a frustration with the narrowness of how resistance in tech spaces is being done. Even in activist spaces, there's such a felt urgency that is resulting in very narrow forms of how we're supposed to express our political activism. A mode in activist organising that's been really present is that need to instantly have the solution. Or to be able to articulate what the solution is all the time. The disconnection between that and our inner queer trans enby selves is massive. Part of TITiPI's flamboyant grey infrastructuring is trying to bust open that space of a particular type of activism.

FS: In the past few days Kate and I have been talking about greyness as non-binary, which I think is really interesting. Grey is often seen as mediocre but it's the space that is neither black nor white. How to do greyness with exuberance – it's great to think about it like that.

FoAM: How can a small institution like TITiPI take a position on something as pointed as 'public interest technology' in a terrain where the grounds are totally shifting?

Longevity and shifting grounds

FS: We started out with the plan to make a temporary institution. One of the issues we had with institutions is that they often become all about their own continuation. All the energy goes into the propagation of the institution itself – that creates really big problems. So part of the ethics of TITiPI when we started was that this should not be the case. Then here we are, five years in, and actually the opposite seems to be happening: it starts to be interesting to think about how to still not do that, but how to think about longevity in very volatile times. What that means exactly I still don't know, but it's understanding that there's radicalness in trying to maintain this structure for the long term. As long as we can, as long as it takes. It seems that's what we need to try.

JR: It's not that TITiPI will only exist while TITiPI is named and that it happens within this server and this host by this group of people. It's understanding that we are an ancestral institution of the future. Doing things whose results we will not see.

KR: One other aspect of TITiPI that I'm interested in is to what degree this work of instituting might be interesting or valuable as a model to others – not a model of what to do but a model of an experiment?

HP: There's maybe two things going on there. One is for us it's sometimes barely surviving the instituting, then wondering what it might mean to share that with others – partly as an internal confidence thing. Then the other is the opacities – with all these networks of organisations that we're working with, there are modes of opacity and smuggling, informal networks that are themselves ways of sharing. That's why a lot of the sharing often happens one-to-one, rather than as sets of instituting examples that others can build on. I can see that's the work that you're also interested to work out, how to make that sharing possible.

🜛

⧉

This article features research conducted as part of the FRICTIONS project, which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 101147188.