Pattern Thinking Across Domains

Pattern as a participatory practice where symmetry breaks into variation, rhythms expand and contract, and transparent rules yield emergent surprise, inviting us to reimagine technology as dialogue, not rupture.

Frameworks for Meaningful Variation

Beneath the steep limestone peaks of Austria’s Salzkammergut, the Hallstatt salt mines cut deep into the mountainside; a labyrinth carved over millennia in pursuit of the region’s "white gold". Here, archaeologists have recovered narrow bands of woolen textile, in indigo, ochre, and moss-green thread. These bands, woven between 720–660 BCE, are material records of pattern thinking in action; each diamond or chevron the product of a precise choreography. When archaeologists examine these salt-preserved textiles, they translate technical details into replicable instructions. The process is both forensic and imaginative: reconstructing what was made and how, what emerges is a pattern language enacted through fibre and motion, where minimal operations – turn, pass, repeat – generate surprising complexity.

Hallstatt textile by Andreas W. Rausch

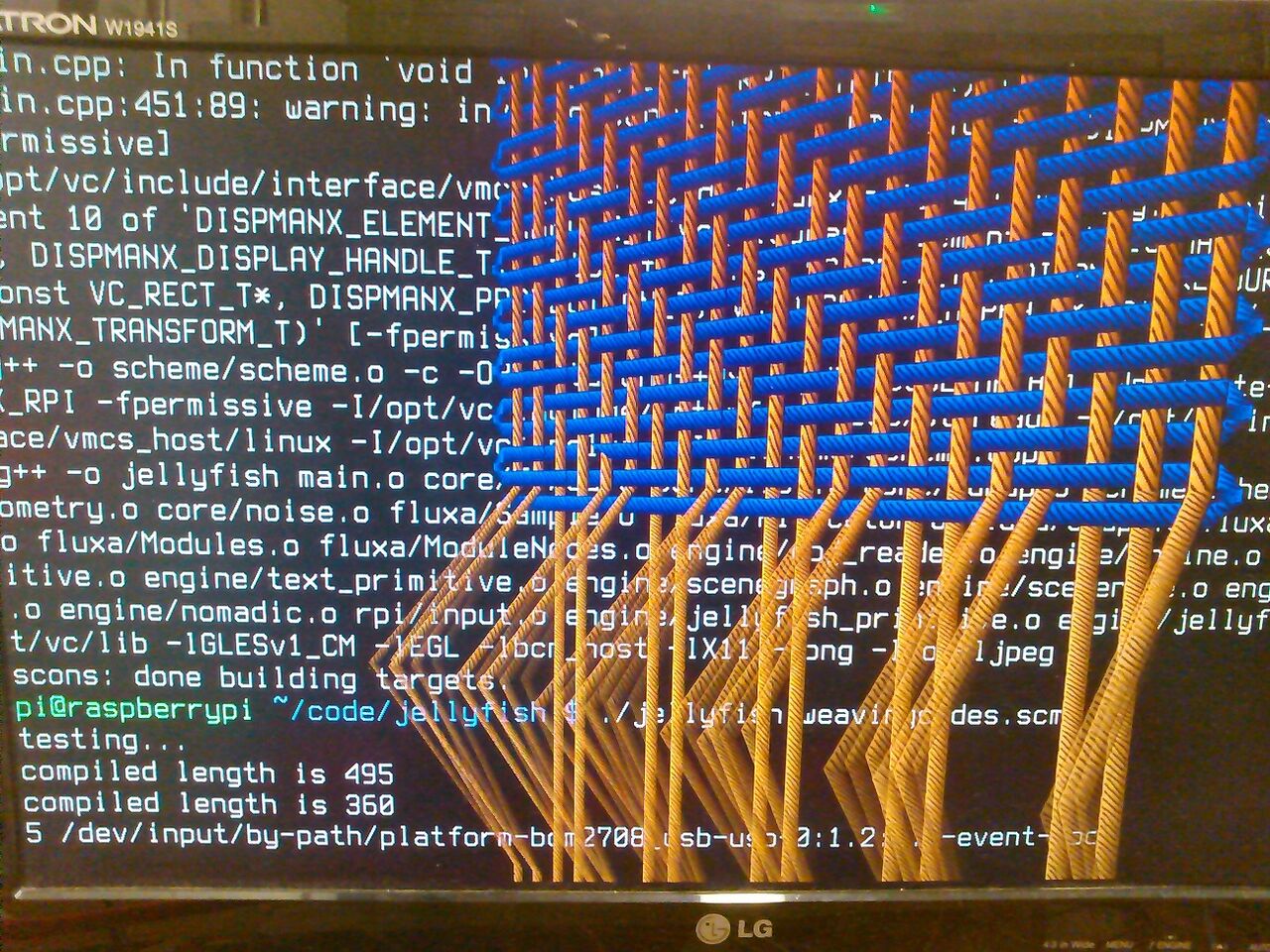

Dave Griffith’s tablet weaving sim

Dave Griffith’s tablet weaving sim

This same logic – that simple rules, iterated and recombined, can yield worlds of variation – threads through Alex McLean's work with collaborators at the juncture of craft and computation. For the project Weaving Codes, Coding Weaves, Dave Griffiths developed computational tools for simulating tablet weaving patterns, creating languages that could represent the stepwise logic of ancient textiles to help bridge traditional craft knowledge with contemporary programming practice. This work approaches technology as a relay; an evolving, situated practice contingent on human agency and collective experimentation. Heritage algorithms and embodied procedures persist, with pattern as a common method: a framework for meaningful variation.

Seen this way, technology is less a rupture than an ongoing conversation with pattern – an exchange where symmetry splinters into variation, rhythms expand and contract across scales, and transparent rules yield unpredictable emergence. As these operations ripple across domains, they reveal patterns not merely as descriptions of what exists, but as invitations to what might be – offering both a lens and a lever for intervention within our shared technological landscape.

Symmetry and Its Breaking Points

Symmetry breaking is a natural process and generative principle, in which a state of uniformity or invariance (its symmetry) is disrupted, allowing new structures, patterns, or behaviours to emerge. McLean explains this through the transformation of water droplets:

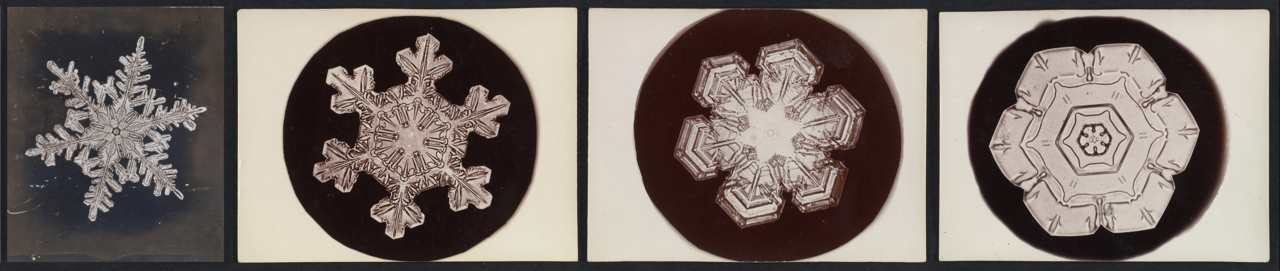

If you start with … the most symmetrical thing, which is a sphere, like a raindrop, and then freeze it so it turns into a snowflake, it creates this pattern … applying some force to this perfectly symmetrical thing somehow creates this less symmetrical thing. We think of snowflakes as being symmetrical, because they are, but they’re less symmetrical than what they come from.

As McLean notes, the snowflake’s intricate form emerges from a single disruption of perfect symmetry – each branch shaped by subtle variations in temperature and humidity as the flake falls. A six-armed star, caught on black velvet. Meteorologist and photographer Wilson Bentley's lens fixes what the world cannot: a pattern birthed by molecular bonds, sculpted by turbulence, vanished in seconds. In Japan, snowflakes are symbols of impermanence; in digital culture, they become icons, memes, insults. Each seeing is a new symmetry, a new break. The sixfold symmetry is never perfect. Every plate is an archive of loss: the flake is long gone, but the pattern remains.

Snowflake photomicrographs by Wilson Bentley

Snowflake photomicrographs by Wilson Bentley

By applying force to symmetry, you break it, and end up with something less symmetrical, but somehow more interesting. It could have broken all these different ways, [but] it has to break in one way, and then you get the pattern.

In the Hallstatt textiles, weavers created complex geometric motifs by alternating tablet rotations, breaking perfect regularity to generate diagonal lines and patterns. This deliberate asymmetry turned simple binary operations into a layered visual system.

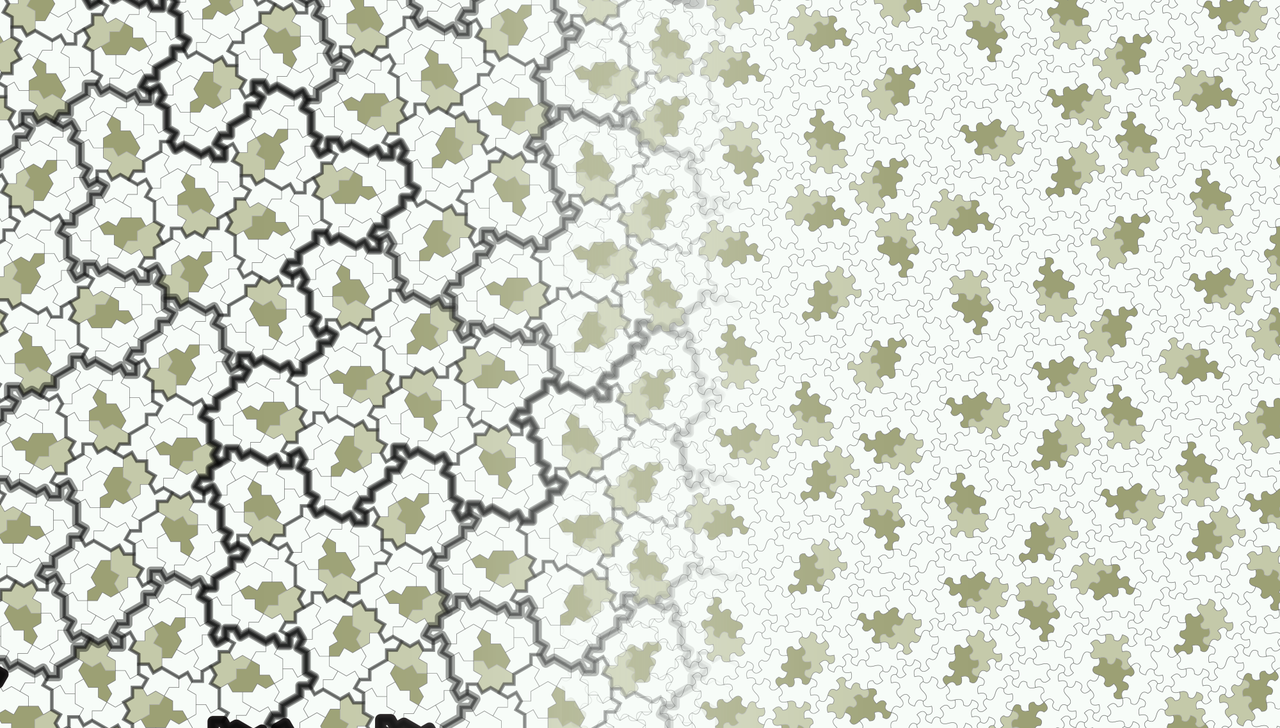

A tiling with the ‘spectre’ monotile, FoAM studio, Vadediji, Croatia.

But symmetry breaking can also be intrinsic to the system itself. Consider the aperiodic monotile (“the hat”), a thirteen-sided shape discovered by an amateur mathematician in 2023. Unlike more familiar tessellations, the hat’s aperiodicity emerges from its geometry alone, forcing each new tile to break the symmetry of its neighbours. Attempts to use the hat in practical settings frustrate craftspeople used to regularity: each new placement demands attention, as no two patches are the same. The result is a surface that resists repetition, holding the eye in a search for order that never quite arrives.

McLean witnessed this same principle in action at the Rudolf5 Algorave in Karlsruhe, where a performer demonstrated how meaning emerges in the space between regularity and randomness:

There was one performance by someone performing as nervousdata. It was completely wild … she was just taking a single pattern and then manipulating it over the space of 30 minutes, in all of these really wild ways. I don't know how to explain it. It broke the mold.

The set began with a predictable rhythmic structure, which nervousdata subjected to a series of transformations; fragmenting, layering, and recombining elements over time. The original structure remained discernible, but was continually unsettled, each new variation emerging from residue of the last.

Meaningful patterns emerge in the space between perfect regularity and pure noise. At either end of this spectrum lies an emptiness. When confronted with perfect repetition, our attention drifts; faced with pure randomness, we disengage:

You can use it almost like silence. Maximum information, but somehow it feels like nothing.

When structure collapses into monotony or chaos, our pattern-recognition faculties find nothing to hold onto; no anchor for anticipation, memory, or interpretation. For pattern-makers, the art lies in mediating between these poles, introducing disruption while maintaining enough coherence to keep listeners engaged in the possibility of meaning.

Using it to make really broken music, there’s something quite nice about that.

When symmetry breaks, it creates reference points that anchor complexity; stable coordinates from which patterns can expand and contract, the next operation.

Expansion and Contraction (operational techniques)

Imagine yourself sitting cross-legged with a teacher, reciting a phrase. Ta-ka, clapping palm to palm, tapping your fingers to mark the cycle. You lose your place, start again: ta-ka-di-mi. Sometimes you catch the syllables, sometimes just the pulse. The pattern grows, splits, recombines; your grasp flickering with each new repetition. Notation offers a map, but in konnakol, the territory is always moving. What you learn is less a sequence of syllables than a way of inhabiting time, felt in the body as much as understood in the mind. This section draws on McLean's paper 'From Konnakol to Live Coding', presented in September 2024 at FARM in Milan.

Pattern-making often involves manipulating scale. In this scene, you're experiencing expansion and contraction; how patterns grow, shrink, and recombine within a stable frame. McLean explores this through South Indian Carnatic rhythms, particularly konnakol – an ancient, living vocal percussion practice where patterns are recited through syllables.

You often hear people “speaking the drums” with syllables, different drum rhythms, but this is a bit beyond that, where the speaking of the drums has become its own practice.

Performers recite, clap, and tap, experiencing patterns that grow and shrink within the underlying cycle, or tala. This practice is both mathematical and embodied; a dynamic play of memory, muscle, and attention, where each repetition shifts the performer’s grasp of the pattern. In konnakol, expansion and contraction are not abstract operations but a core method for generating complexity and variety, transforming simple motifs into intricate, evolving structures.

Konnakol syllable groups, or solkattu, are recited in expanding patterns to create rhythmic variation. Try speaking these aloud, feeling how the pattern grows:

> ta-ka (2 syllables) | ta-ka-di-mi (4 syllables) | ta-ka-di-mi-ta-ka-di-mi (8 syllables)

Each step doubles the density, embedding expansion within a fixed tala cycle.

In Carnatic music, yati patterns govern how rhythmic phrases expand and contract within a tala. As McLean explains:

You have this repetitive structure that’s running underneath, repeating over and over again, and you divide up time so it perfectly fits that. But you’re also doing these rhythmic transformations where you’re adding and subtracting beats over time. You might start with one beat and then add a beat each time until you get to a certain point … and then shrink again.

Here, yati is a negotiation with time and structure: phrases swell and contract, tension builds and releases, with the performer’s choices anchored by the underlying tala cycle. For example, Samayati yati remains constant (e.g. 4–4–4), while Damaruyati follows a 4–6–8–6–4 sequence, embedding both expansion and contraction within an eight-beat cycle.

In konnakol, expansion and contraction are lived through voice and gesture. Translating these operations into TidalCycles An open-source live coding environment McLean designed for improvisational pattern-making. means reimagining them as discrete functions: `slow 2` stretching a cycle, `fast 3` compressing it, with `iter` tiling patterns across time.

McLean's goal is to create tools that invite negotiation, while leaving space for performers to make decisions in the moment. This translation brings new affordances: patterns become shareable, open to collaborative invention. But this same shift disembodies the pattern; the subtle inflections, microtiming, and the feedback between teacher and student, performer and audience, all risk being flattened into the grid.

An exchange between McLean and his konnakol teacher, B.C. Manjunath, makes these stakes clear:

I’ve shown [Manjunath] some of what I’m doing [with live coding], and he finds it quite strange, I think. It’s a really precise fit into the grid, which is very different from playing mridangam.

Where computational systems are often imagined as rigid or abstract, live coding occupies a hybrid terrain: algorithmic yet deeply performative, improvisational, and responsive to the moment. As discussed in From Scratch?, live coding emerged as a reaction to the opacity of programming, making process visible, participatory, and legible to interpretation. Yet, as Manjunath’s response suggests, even this introduces its own grid; a logic of precision and constraint. The friction here is not a clash between body and machine, but a dialogue between two traditions, each with its own ways of shaping time, variation, and meaning.

In developing Tidal, McLean has worked to implement both additive and divisive logics, allowing users to build patterns by combining or subdividing beats. But even when the environment is capable of both, how these options are presented – the defaults and interface choices – shape what becomes possible. Where should agency reside: in the user, or the tool?

As a computer programmer, the point, the decision point is … what you leave up to the human and what you try to automate. You could have some solver which would come up with the right number of expansions and contractions to fit the tala structure, so that human wouldn’t have to think about it at all. But that feels like a step too far…

McLean’s reluctance to automate this process preserves space for negotiation, allowing performers to engage directly with structure and variation. Interface choices do more than streamline syntax and workflow: they shape which rhythms are available, whose traditions are legible, and how agency is distributed. As this example shows, the design of pattern systems becomes a site of cultural and political decision-making.

The questions of agency raised by expansion and contraction intersect with the final pattern operation: structured randomness, where transparent processes yield unexpected emergence.

Structured Randomness

Step into the lobby of internet security provider Cloudflare's San Francisco headquarters, and you're met by a wall of a hundred lava lamps, wax blobs drifting in slow motion. This isn't just retro decor; cameras capture the swirling patterns, digitising each moment into streams of numbers that seed cryptographic systems protecting millions of connections. Part security infrastructure, part public art, the wall bridges "true" randomness and computational processes; a hedge against the predictable logic of machines, yes, but also a self-aware gesture of transparency in a field marked by black-boxed systems.

As images of this system circulate through tech blogs and keynote slides, it transforms into corporate folklore — making the invisible work of security tangible, strange, and open to interpretation. What matters here isn't just the randomness, but the invitation to witness the negotiation between entropy and algorithm, the performance of openness and the realities of cryptographic practice.

But you don’t need a wall of lava lamps to court unpredictability. Sometimes, all it takes is a card.

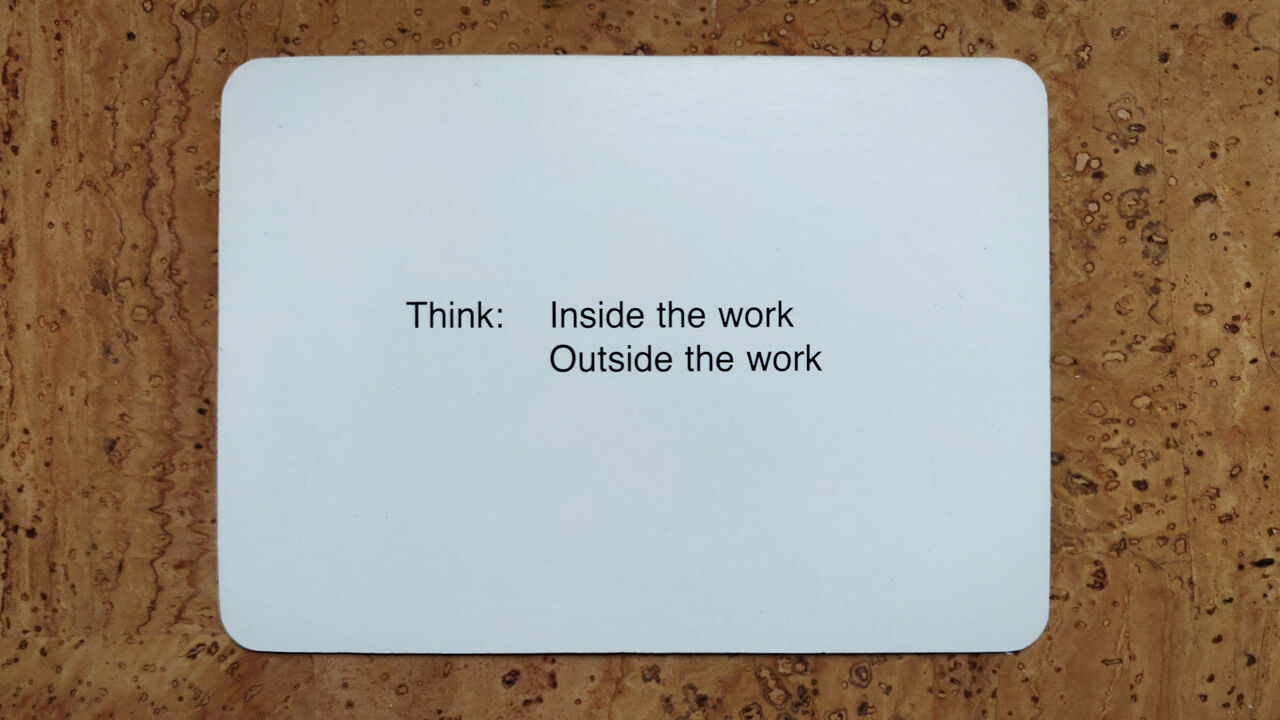

In preparing this text, I reached for Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt's Oblique Strategies deck. This is randomness in miniature; a system balancing unpredictability with bounded selection. The process of drawing a card is visible and tangible, while the deck creates bounded unpredictability, its 103 cards a large enough set of possibilities that each draw creates genuine surprise.

The card I drew:

I sat with this prompt, wondering which vantage point I’d been writing from, and which escaped notice. The card directed my attention to a core dilemma: the logic behind a system may be clear to its creator, but opaque to its audience. Reflecting on this prompted me to revisit McLean's practice with fresh eyes.

Where Cloudflare obscures its randomness behind corporate spectacle and Oblique Strategies offers bounded selection, McLean's approach reveals the generative possibilities when the mechanisms themselves become visible and manipulable, turning randomness from a black box into a site of collective agency.

McLean reframes randomness as, itself, a form of pattern-making.

With a pseudo-random number generator … the idea is to make a pattern that’s as long and arbitrary as possible.

In computational systems, “pseudo-random” sequences appear unpredictable but follow deterministic rules, A pseudo-random number generator, or PRNG, is an algorithm that, given a starting seed, outputs a reproducible sequence of numbers that appear random. while “true randomness” derives unpredictability from naturally-occurring physical processes like atmospheric noise or, as in Cloudflare's case, lava lamps. McLean finds neither approach satisfying:

I tend not to use random number generators, but still … embrace the unpredictable determinism, which you associate with random number generators.

Where Oblique Strategies creates bounded unpredictability through physical cards and fixed prompts, McLean's translates this same principle into computational form. Instead of drawing from a fixed deck, he hand-crafts systems where the “cards” themselves can be modified, recombined, and transformed in real time.

You’re setting up something where … you’re making something unpredictable. You’re bringing these things together, in a way where you don’t know exactly what’s going to happen, but which you anticipate is going to be something interesting …

From the creator's vantage point, each operation unfolds transparently, step by step. From within the audience, these same steps – layered, recombined, and transformed – produce a surface of apparent unpredictability.

You might have a sequence, and then a few transformations working with each other, and then start patterning the parameters of those transformations so that they jump all over the place and create something … deterministic but unpredictable … where if you change one starting condition, then you end up somewhere very different.

This sensitivity to initial conditions is what makes the system both playful and revealing; adjusting these starting parameters lets performers and audiences map out the system’s underlying logic. By re-running the operation, they begin to sense the tendencies of the rules at work, feel the contours of possibility – even as it remains impossible to predict specific outcomes.

At the same time, even systems built on explicit rules can surprise their creators. As McLean describes:

You make this thing, which is … generating these unpredictable patterns … that fall into a pattern, so you get to know them after a while, but you don’t know exactly what’s going to happen.

Here, the process is not about imposing order from above, but sustaining a dialogue with the system, learning its tendencies over time. McLean moves between composer and explorer, crafting rules, then surrendering to the patterns they generate.

Structured randomness, then, is a site of negotiation over who gets to see, to understand, to intervene. Approaches that make pattern generation visible and manipulable, like structured randomness, provide an alternative to technologies that either dictate outcomes or obscure their workings.

Returning to that Oblique Strategies card (“Think: Inside the work | Outside the work”), what McLean's approach accomplishes is a conscious blurring of these boundaries. Where many technologies maintain a hard division between those who understand the internal logic (developers, engineers) and those who only experience the outputs (users, audiences), McLean's systems stage a permeable membrane between inside and outside, rejecting the hidden mechanisms that characterise much of our technological landscape.

Pattern as Participatory Practice

These explorations reveal not a universal grammar of pattern, but something more supple: an ecology of practices building upon one other. Symmetry breaking seeds variation in Hallstatt diagonals and snowflake facets; expansion and contraction shape those seeds within a cycle; while structured randomness, whether in lava-lamp cryptography or hand-shuffled Oblique Strategies cards, turns transparent rules into emergent surprise. Together, these operations train our pattern literacy, revealing how minimal rules can generate worlds of variation.

Like archaeologists deriving weavers' gestures from salt-preserved fragments, McLean and his collaborators reinterpret patterns across gaps of time, media, and tradition. Yet this work differs from pure recovery; it distributes creative agency across time and between participants, acknowledging how patterns are continually remade through use. This commitment to preserving human agency within technological systems manifests in specific choices: favouring deterministic unpredictability over stochastic functions, leaving creative decisions to humans, and making pattern-generating principles visible and manipulable.

You too can adopt this ethos. When you code, weave, or improvise, project your controls; display your code, remix your starting parameters, build tiny “lava-lamp” workflows to foreground where chance enters your systems. Remain attentive to those moments where control slips from your fingertips, and choose to make them visible. Much as a single tile or syllable can transform a pattern, small interventions in technological systems can cascade into more participatory futures. The vision emerging from this cross-domain exploration suggests technology as an extension – tools making visible the choices that shape them, with pattern as a bridge connecting past and future, algorithmic precision and embodied knowledge, in an unfolding conversation that remains perpetually open to surprise.

🜛