The Jacquard Mistake

Concerning certain adjustments to the counterweights, and what was lost. Or: a ghost story about looms.

Cardstock swells. Metal guides strain. Brass gearing stutters against its own precision.

Silk snaps. Other threads loosen. The pattern breaks.

Fingers working to clear the guides. Springs that should yield, don't. The mechanism seizes. Teeth catch flesh.

Recoil. A sharp bark of pain cuts through the whispers. Dark stains spreading – silk and skin, wine-red on cream fabric. Blood threading between fingers, droplets marking the waxed stone.

Gasps. A woman's cry, high and tight. Fabric rustling, bodies shifting. The circle widens, space opening around the mess.

Warm varnish. Sheep tallow. The scent of fear mixing with metallic sharpness – iron, salt, a bitter intimacy.

Cards catch, buckle, tear. Threads shriek past breaking – snap – go slack.

The bus station spreads beneath the concrete car park, a system beneath a system: twenty-five stands marked in weathered letters. Fluorescent light pools on perforated metal. Saturday: families with shopping bags, teenagers idling, knees and tote bags pressed into rows. Stand S, 302 Golcar Circular. The bus arrives with a pneumatic sigh, opening to disgorge passengers into the brightness.

Upstairs, kids take the front seats. The route curves as we climb, foliage skimming glass as we pass converted workshops and stone walls. Stone warms as the ground lifts; the uniform grey dropping away. We thread the viaduct twice – river, canal, and railway drawn tight into one corridor. Mills and old sheds crowd the waterside.

Then the sky opens. A child at the front presses a hand to the window. The settlement loosens – verges widen, houses stand apart: semis, then detached. Pub, post office, pharmacy. Fresh wreaths at the memorial. The bus stops at the Co-op branch on Town End. I step out between parked cars, crossing by the church, to find the textile museum set between terraces.

⧢

The admission desk sits beside a rack of local guidebooks, postcards, tea towels, self-published pamphlets. “Textile demonstration's just finishing upstairs,” says the man behind the till, handing me a ticket and a photocopied map of the cottage layout. “You'll want to start with the ground floor, work your way up.”

I move through the reconstructed rooms – Victorian kitchen with its black-leaded range, parlour furnished with working-class propriety. Upstairs, a display case in the corner of a first-floor bedroom catches my attention: photographs and documents (membership cards, meeting minutes, radical literature) from the end cottage’s fifty years as headquarters of the local Socialist Club. The space had continued evolving, adapting to different needs across decades, not frozen in Victorian amber.

The final staircase grows brighter as I climb. At the top, a long chamber extends beneath the cottage's roofline, mullioned windows casting diamond patterns across worn floorboards. The space feels different – not preserved but occupied, designed around the specific requirements of precision work.

“...and you can see how the heddles lift the warp threads to create the pattern,” a woman's voice concludes. Parent and child stand beside one of two large handlooms, a mother nodding with dutiful attention while her son fidgets, eyeing the exit. “Any questions? No? Well, enjoy the rest of your visit.”

They edge past me with polite smiles, and I'm left with the volunteer, who turns back to the loom with an expression suggesting the real work begins once official demonstrations end. She adjusts something in the mechanism – a small brass fitting I hadn't initially noticed – and the entire frame shifts, heddles rising with a different rhythm.

The loom responds to her touch like a living system, threads catching the light. A second loom waits alongside, its shuttle positioned as if work had only just paused. At the far side of the chamber, a doorway leads onward – spinning wheels and equipment visible in the adjoining room – but here, everything focuses on these two machines and the volunteer.

“Interesting, isn't it?” she says, noticing my attention. Her accent carries traces of elsewhere – American, maybe, but not easily placed. “Most folks want to see the clogs, but this is the work. The loom keeps its hour.”

Her phrase hangs in the air. Before I can process what feels strange about it, she's adjusting her cap and guiding my hand to the shuttle race. “Feel how the thread wants to move,” she says. “It’ll tell you when the tension's right.”

I press my palm against the wooden mechanism. There's a subtle responsiveness – not quite resistance, but a kind of invitation. The shuttle slides with unexpected precision, its path calibrated to something more sophisticated than I'd first assumed.

“Most people miss the counterweights,” she says, demonstrating how the brass adjustment shifts the entire mechanical relationship. “But watch this.” When she adjusts the counterweight by a single notch, the change flows through the entire mechanism, recalibrating relationships, creating space for more complex negotiations between warp and weft.

I watch her foot find the pedal's sweet spot – not the broad, crude pressure I'd expected, but something more like a conversation. The resistance builds gradually, offering feedback I can feel through the shuttle race. A clean bite, then give; slack arriving on cue.

“This one's been running since my grandfather’s time.” She runs her finger along wear patterns in the brass fittings. “Each generation adds something. Small things, but they add up.”

The chalk marks on the adjustment rails catch my attention – deliberate scratches positioned with obvious purpose, though I can't decode their meaning.

“The interesting thing,” she says, demonstrating how foot pressure translates into thread control, “is how your legs learn to read the wool. After a while, you know when a thread's about to go. Feel it in your calf before you hear it.”

⧢

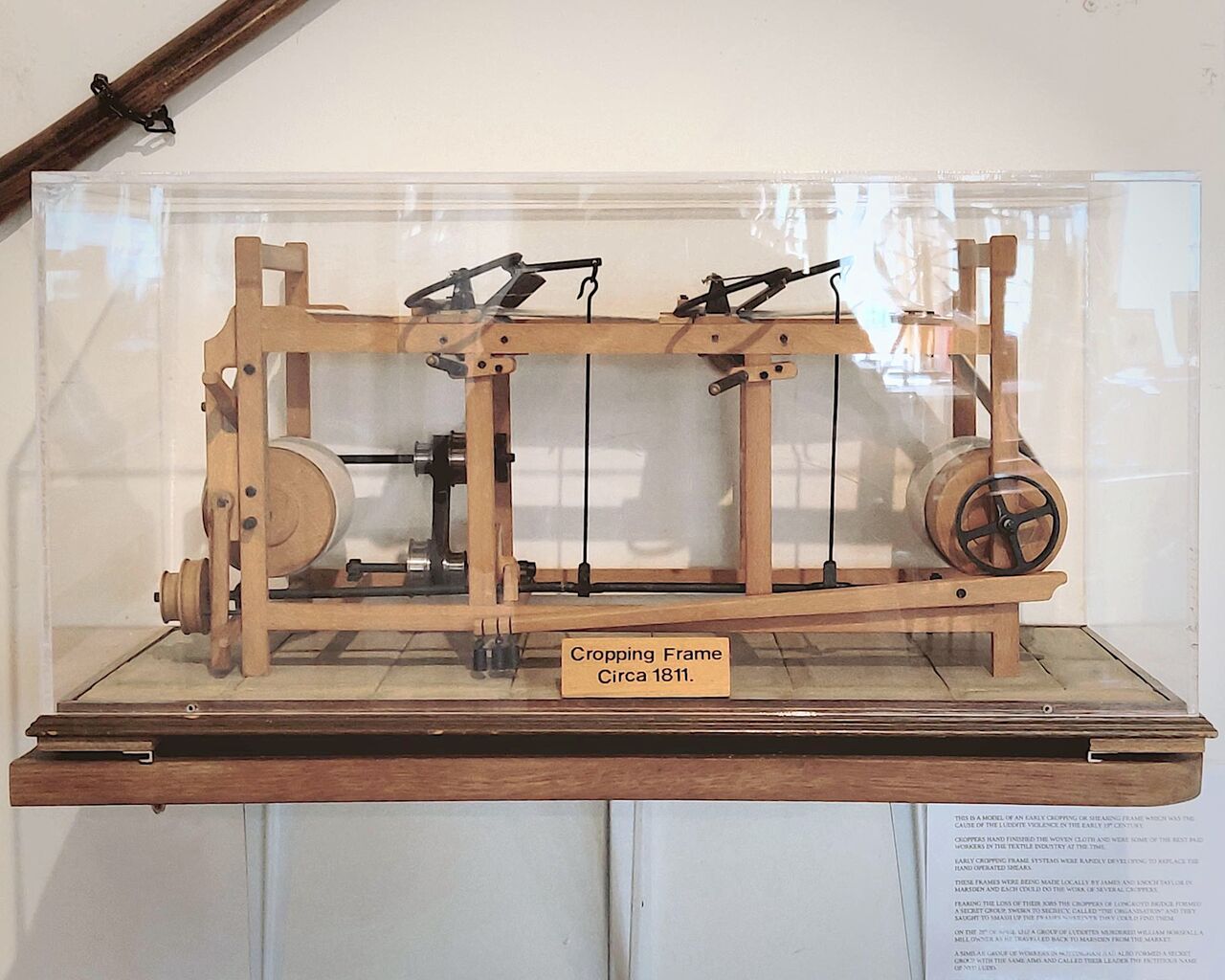

Moving across the room, my eyes alight on a wooden frame behind plexiglass, perhaps eighteen inches long, but built with a meticulous attention to detail. The placard: Cropping Frame, Circa 1811

“Oh, that one's interesting,” says the volunteer, appearing beside me. A maker, she'd mentioned earlier, whose mother had been a weaver. “Shame it’s only a model. A frame learns the shop; behind glass it’s all surface – no slack, no bite. If it can’t throw you, it can’t teach you.”

I lean closer to examine the tiny exposed gearing, the carriage rails scaled down to doll-house proportions. Miniature shears riding a track across a table where broadcloth would run stretched. The cropper's vertical cut turned horizontal, belts ready to take whatever power a room could spare. Yet every gear and pulley remain visible, reachable – meant to be tuned mid-run.

She studies the scaled-down mechanism through the case. “Label makes it seem like they cleared rooms,” she says. “But look – six feet, timber legs. You brace this into the old bench. That’s a shop tool, not a bolt-down.” She talks in lengths – span to span, bench to rail to table lip – and comes up short against the glass.

“Round here you keep heel and wrist in the bite,” she continues, distantly. “Some shops let go; we didn’t. When the cloth runs heavy, you keep a finger in the weight – drop the hand and the weight runs the room.”

I watch her face, noting an odd blind spot in her gaze. Mounted above the case, a hammer throws a clean shadow – the only weight here that still lands.

“People make them the ending”, she says. “We used it to spare the back. Let the frame carry; keep the edge with the body.”

The glass eats the weight. What remains is bright and exact – no floor-echo, no give in the rail.

⧢

On the trestle by the window, a stack of bound boards: ‘Examples of period textiles.’ She shakes her head. “They think they were just pattern books. You can set a room off these.”

She sets one down as if it were a tool, not a relic. Quarter-sawn oak boards, two brass posts through the spine, one nut newer. Bound like a book, but the pages are cloth – worked, not display swatches. The hinge gives a dry creak as it lies flat, made for many hands.

“Are we allowed—?” My museum training rises like a brake, but she’s already turned the board so light catches the lines. “Cradle here. Lift from the wood, not the sample. Oils fix the chalk.” It’s heavier than it looks. As I slide a thumb under the corner, the smell rises: lanolin and tallow; old wool fat holding the room’s weather. When the cloth lifts, a rectangle of paler wood shows where it lives. This isn’t a sample so much as a setting – the weight and soak this cloth, in this room, on this day, could bear.

She taps a faint mineral sig. “Quarry chalk. Cuts clean, doesn’t smear like the soft stuff.” A thin brass pin is colder than I expect; the table’s lip has a groove where a line was hooked and tensioned, again and again. “The chalk tells you where to set the weights,” she says, pointing from the mark to the counterweight rail.

“It’s damp out,” she says, moving to the loom. “So we start one notch shy.” She slides the counterweight inward, lifts a small stop on the rail, and shortens the pedal throw. “New leg on the frame, so we soften the catch.”

“Feel here.” She guides my foot to the pedal's sweet spot. The counterweight translates thread tension into resistance, turning invisible forces into a gradient the body can read. The initial firmness as the counterweight engages, the subtle yielding as tension approaches the thread's elastic limit, then that final lightness – one breath before breakage. Everything draws in around foot and rail; the load settles close.

She sets a small brass index onto its rail, and the curve shifts. The last lightness arrives a fraction sooner; my calf answering before I do.

“Fine on a dry morning,” she says, crossing to the window, “but on a day like this, the weight bites too soon.” She loosens the window latch a thumb’s width. Cooler air threads in; the lanolin sharpens. She nods at the pedal. “Try it now.” The catch eases underfoot – same mark, different air. The room is part of the mechanism.

A visitor leans in: “So... this is what did them out of a job?” Tapping the weight once, the pedal eases; the bite goes quiet. “Jobs change,” she says to the rail. “Hands stayed in.”

For a split second, I see both systems at once: the museum loom with its peg-and-bar simplicity, and — occupying the same space — this other mechanism, brass and chalk solving problems that were never allowed to emerge.

In the corridor, a radio crackles: “Closing in fifteen.”

She resets the stop one shy, and steps back without looking at me, leaving the window a thumb’s width open. Same mark, different air. No stutter.

⧢

Third Thursday, after the last demonstration

Someone was saying how weaving became only pictorial. Flat. As if threads could forget their own thickness. One small adjustment to the counterweights, and we might have ...

🜛