Hymn for the Relational

Through sketches, material samples, and embodied observations, we follow Leia's wandering through the intergenerational atelier she is building for and with her spatial family. With the wind, the sun, and the moon as her allies, Leia creates dynamic spaces that insert life in the built environment. Breathing with the rhythm of natural forces, her practice emerges as a series of sensitively crafted relationships, with gravity, atmospheric conditions, and the seasons. The Hymn for the relational is neither theory nor fiction. An immersive, multifaceted narrative highlighting our capacity to sense the in-between — to perceive, nurture, and craft within what was considered empty.

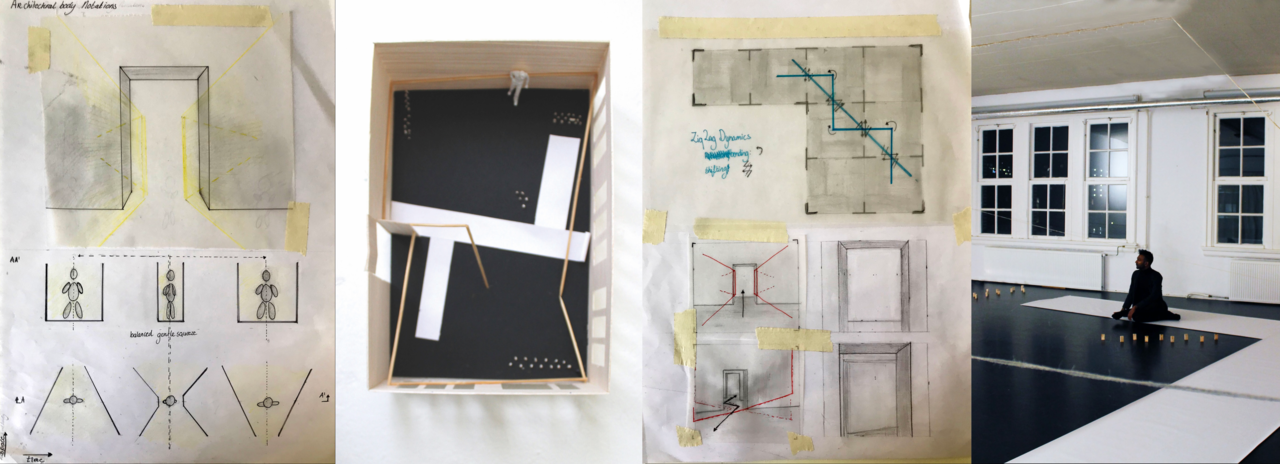

Leia’s practice extends the human sensorium, revealing subtle experiences that modern design typically obscures. She documents the moments when small architectural adjustments activate new awareness. For Leia, technological reimagining occurs through perceptual changes. A diagonal shift, an unbalancing floor, a diffracted light pattern — these suddenly reveal the reciprocity between bodies and environments. Leia rejects both faceless collectivism and Randian individualism Where Howard Roark in The Fountainhead declares “I wish to come here as a conquering emperor,” Leia approaches sites as a respectful collaborator. She moves with environmental rhythms, improvising in the here and now, allowing form to emerge through collaboration rather than conquest. Leia’s raw material should not be thought of as form but as deformation. Her approach reveals architecture as a collective, corporeal practice, where the binary of natural/artificial dissolves into a mutual incorporation, rendering architecture — the act of architecting — as a technology of relation.

Facets of an Archi-Nymph

Attune to the energies of the in-between.

See with the colours of the wind.

Connected to the fire of the earth, grow wings.

Reach out to the moon in the dark cold nights and the compassionate warmth of the sun. Connect celestial bodies.

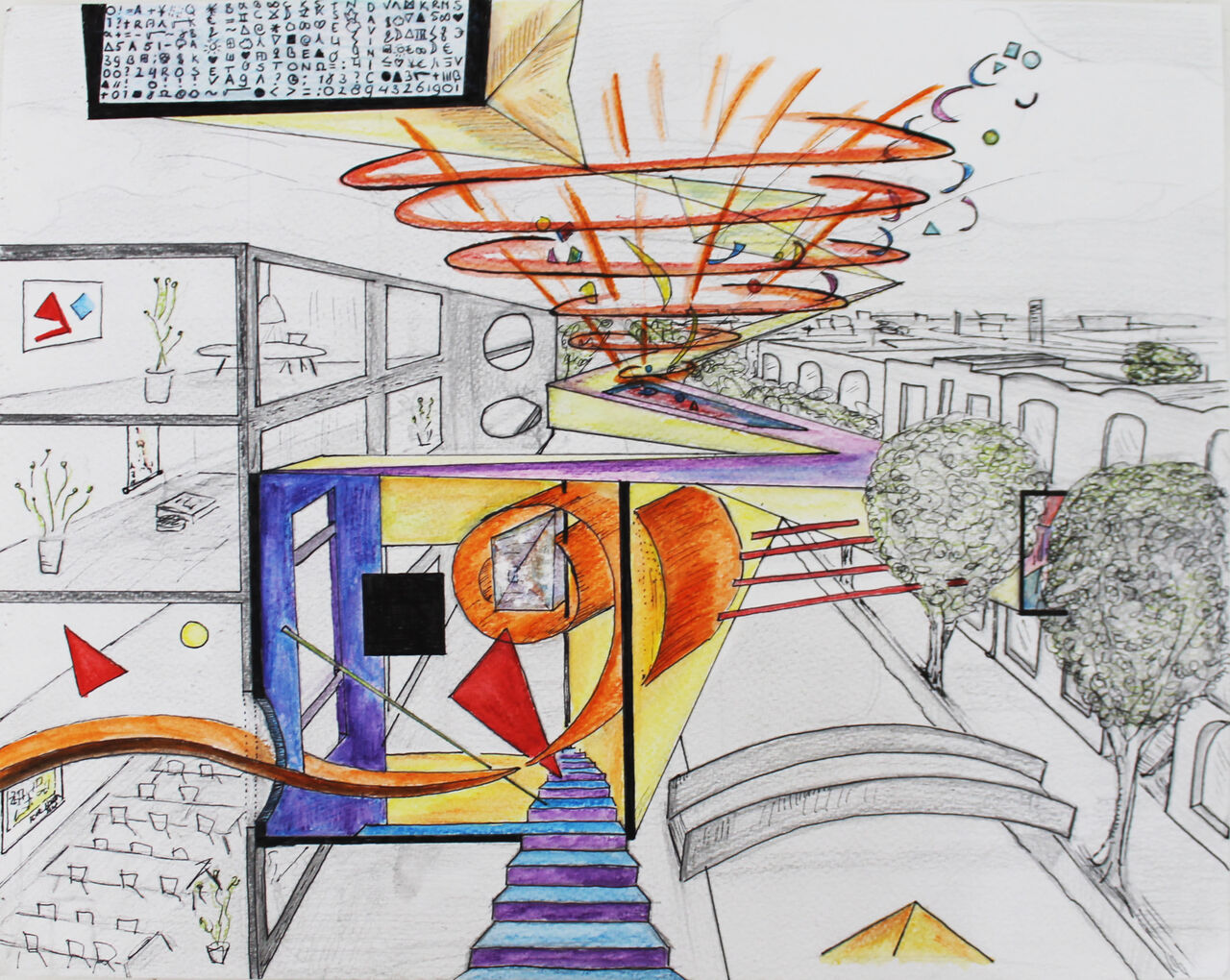

I am aiming at my Northern Star. I’m building an intergenerational home, an atelier and creative residency for and with my spatial family – artists, architects, scientists, body-workers, activists and other cross-species alike. We are driven by a shared affect, a collective rumbling of stomachs. With hands in the dirt, we build a place for nurturing ecological consciousness, a subtle spatial intelligence for the in-between. [A] condition of being alive to the world, characterized by a heightened sensitivity and responsiveness, in perception and action, to an environment that is always in flux, never the same from one moment to the next.

Tim Ingold

One can think of this place as a commonplace. Commonplace books, or commonplaces, emerged to compile knowledge usually by writing information into books. Sometimes commonplaces were required of young women as evidence of their mastery of social roles and as demonstrations of the correctness of their upbringing

Susan Miller. A place that activates knowledge both spatially and in written form. Literal and literary, a place where knowledge is movement. Like stories embedded in aboriginal landscapes, Or a Monstercode activating knowledge requires a direct connection to the land, a zigzagging across space and time.

Site for the Here and Now

The intergenerational atelier is my new landing site. An architecture of the here and now, where we entrain with the rhythms of the earth. Entrainment: when rhythms find each other and sync – like musicians finding the same beat, or how we end up walking in step with a companion without trying.

On crisp mornings, I imagine myself walking around our site. I feel the cold air in my lungs, and the sun warming my skin. Always moving with environmental rhythms, allowing form to emerge through collaboration rather than conquest – activating our atelier as a generator for spatial magicking.

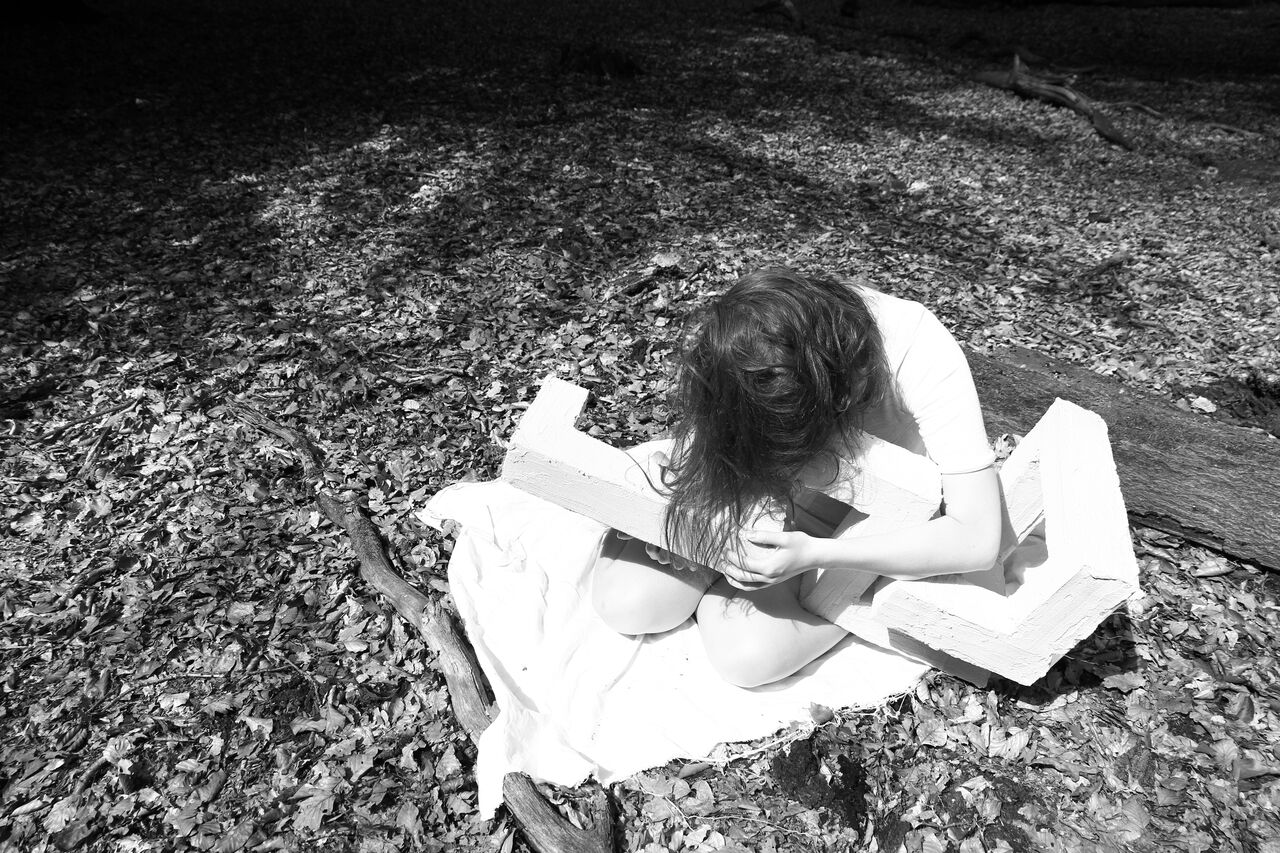

Our collaborative practice is guided by spatial practitioners who listen, move, and breathe with their surroundings. Instead of envisioning buildings or architectural theories from a distance or behind a desk, we value hands-on experimentation and full body immersion in the landscape.

In indoor and outdoor studios, we experiment and improvise, create and contemplate. In a sunny workshop, we carefully rehearse the complexities of our projects, tracing and tweaking spatial arrangements with our bodies. In the garden, we are immersed in an intensive play with the wind and the soil. In the conscious-body-spaces we explore contemplative and performative practices, from body-weather to breath work. Ritual spaces stimulate entrainment and mutual corporation, aligning our personal rhythms with those of the earth, and in a spacious studio we have established a movement practice that challenges our cognitive and sensitive capacities. Performing the Unknown

We long for a creative practice that moves beyond generally accepted conventions – clean and comfortable – in favour of spatial rituals that embrace the unknown. Transforming architecture from a practice of master builders to a craft that foregrounds ecological relationships.

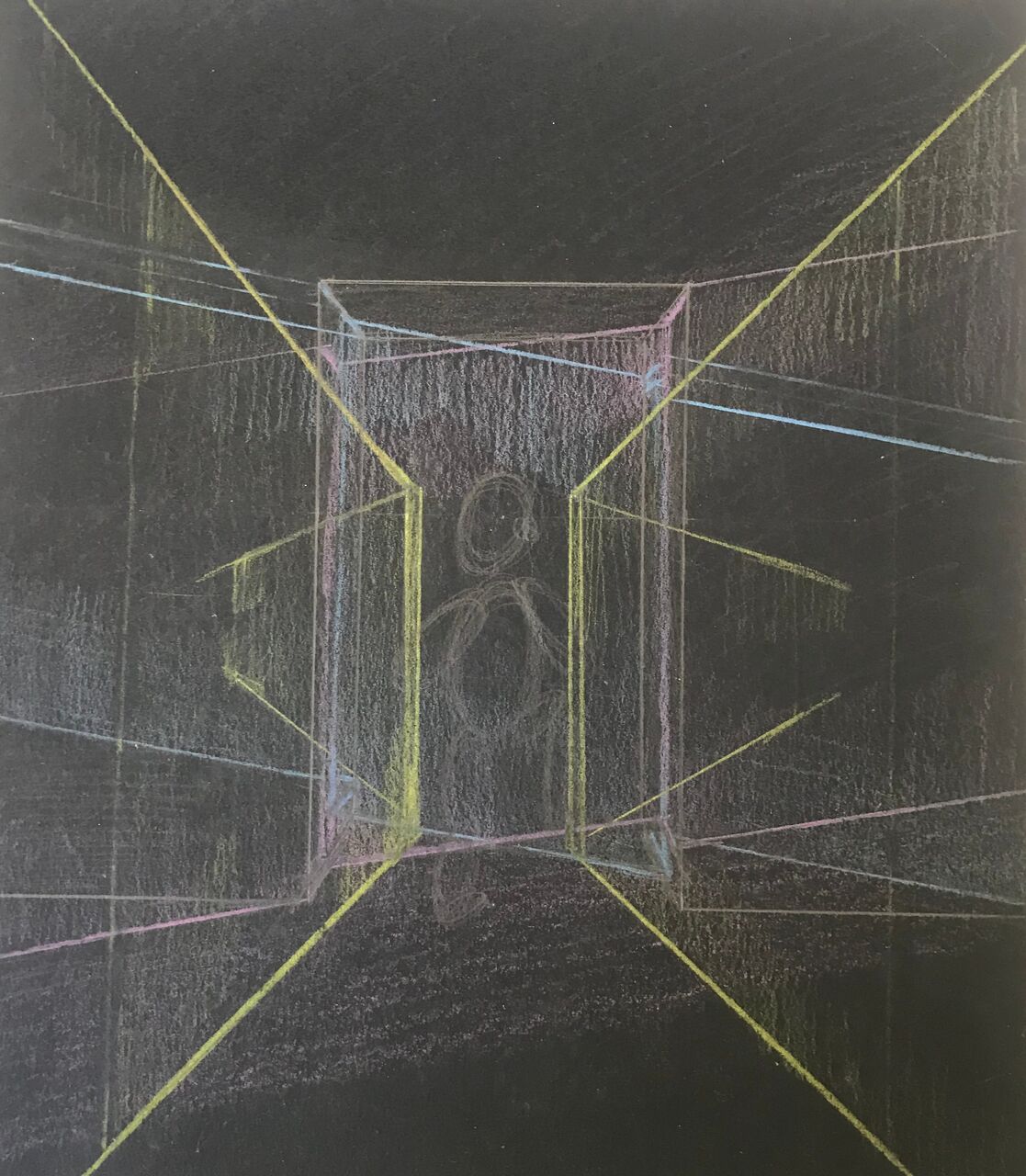

Meandering Geometries

We typically orient ourselves using gravity, the sky, and the rotation of the sphere as unquestioned anchor points. Try this experiment, inspired by James Gibson’s Ecological Approach to Visual Perception: Stand in a wide stance, bend forward, and look through your legs. Notice that the world remains visibly upright; the sky always appears on the upper side of the horizon.

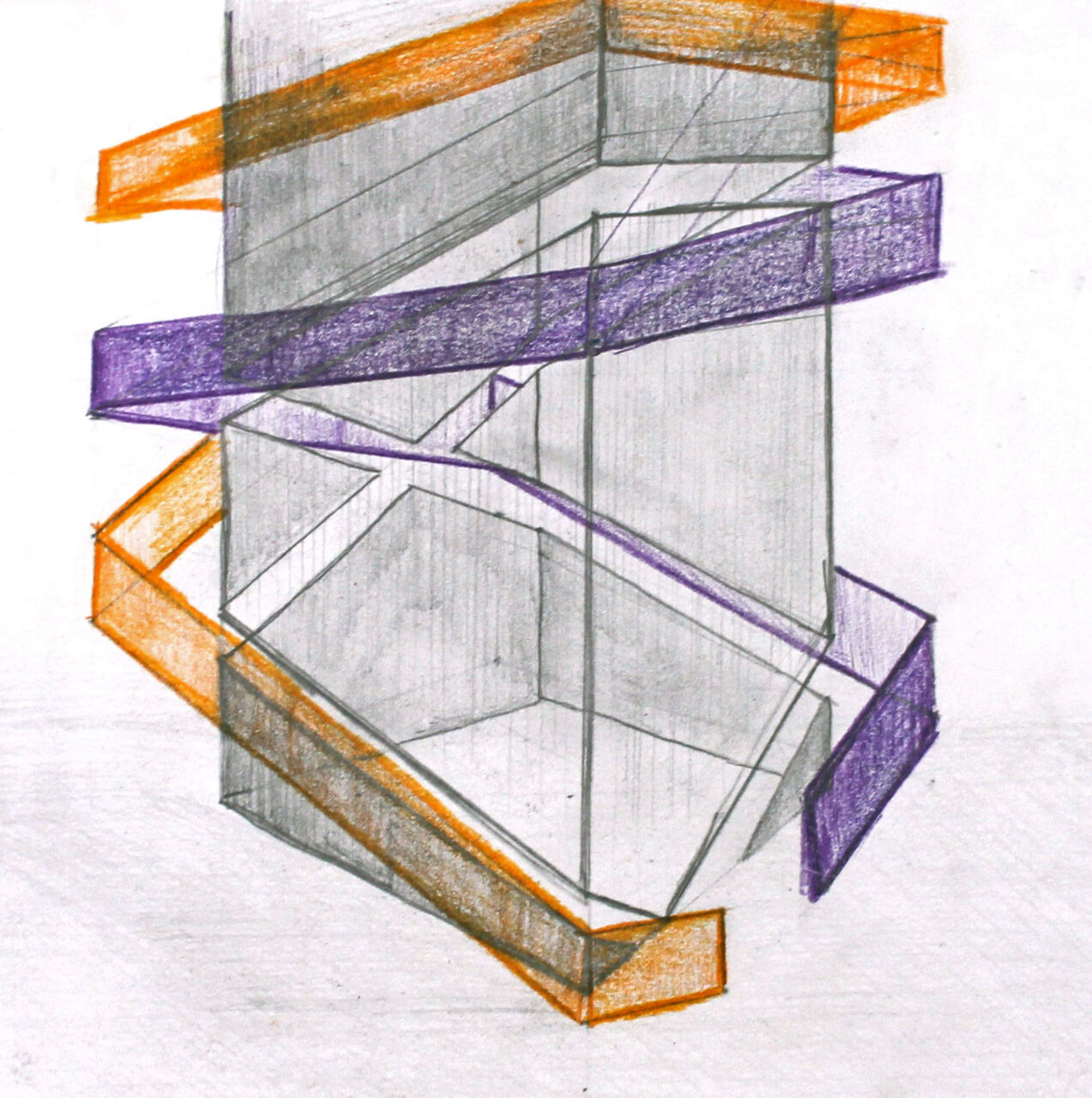

Meandering geometries offer liberation from these pre-conceived horizons. Disrupting normal orientations, they force us to experience space differently. Rather than following a vista or narrative, meandering geometries throw one off balance, extending the open-present of locating oneself.

The components of these geometries are observed successively, bending the movement path or obstructing a line of vision. Such observations are always based on the viewer’s movement. Spatial configurations on the move, they establish a dynamic reciprocity between social and cosmic bodies.

Through small adjustments – a diagonal shift, an unbalancing floor, a diffracted light pattern – I notice that my body is not only ‘reaching in’, to re-establish a sense of balance, but simultaneously ‘reaching out’, to dynamically align with the heaviness of the earth, the orbit of the sun, and the horizon. I am aware of my position, not in relation to an architectural frame of reference, but to environmental movement itself.

Crafting the in-between, nurturing an ecological architectural consciousness and subtle spatial intelligence, I use meandering geometries as agents of change. They have the power to enchant, transforming one’s embodiment with and in the world.

...their magic resides in their mobility, that is, in their capacity to travel, fly, or transform themselves; in their morphing transits ... to live among [them] is to have motion called to mind – and this reminding, too, is a somatic event.

Jane Bennett