From scratch? Live coding as creative interface

Unsettling the boundaries between composition and improvisation, performer and audience, process and product.

Alex: I guess there’s something about projecting your screen … sharing what you’re typing in. Sometimes you do see people noting things down. I don’t know, I think you get a lot of ethnographers …

Justin: That’s my shtick! I like that, yeah, people taking things away.

Alex: What percentage of this audience are ethnographers? [imaginary show of hands]

Justin: Oh god, there’s more.

This wry exchange captured something essential about live coding: how it transforms observation into participation. While ethnographers observe the practice from the outside, live coding itself emerged from a desire to make visible what computing culture normally hides — probing programming's creative possibilities, re-imagining code as a medium for live performance and shared discovery.

Conducted in September 2024, this conversation with Alex McLean, who has helped shape and steward the practice from its origins in the early 2000s, traces how this vision evolved from individual experimentation to a community-driven practice that challenges conventional assumptions about what technology can be and how we might relate to it differently.

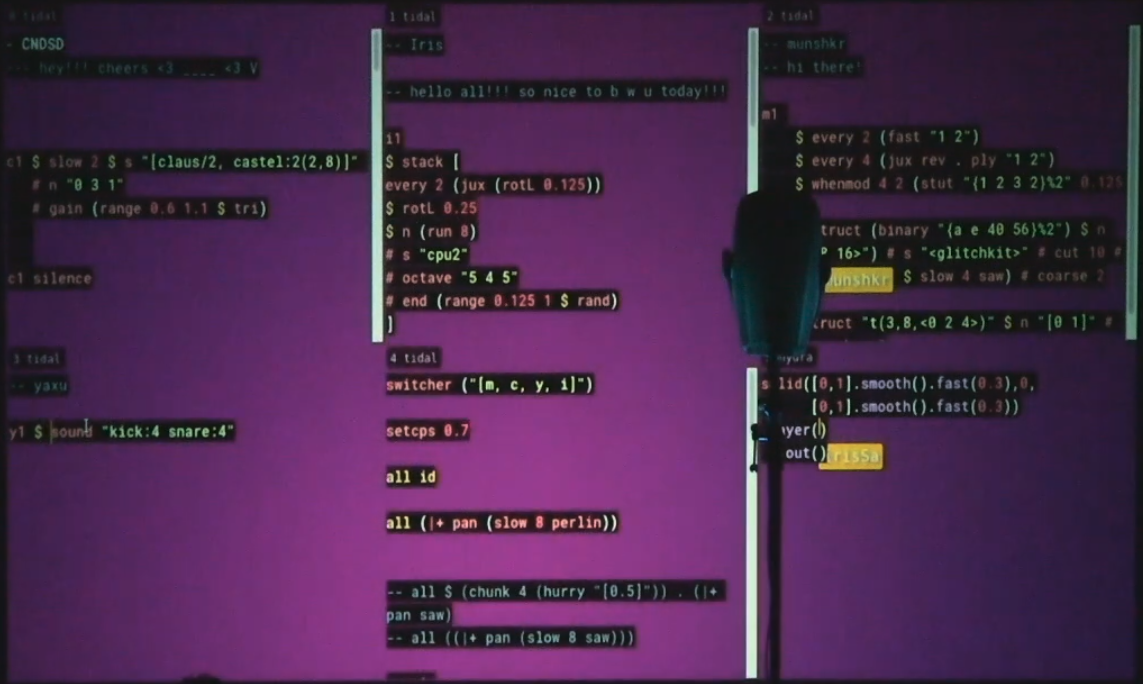

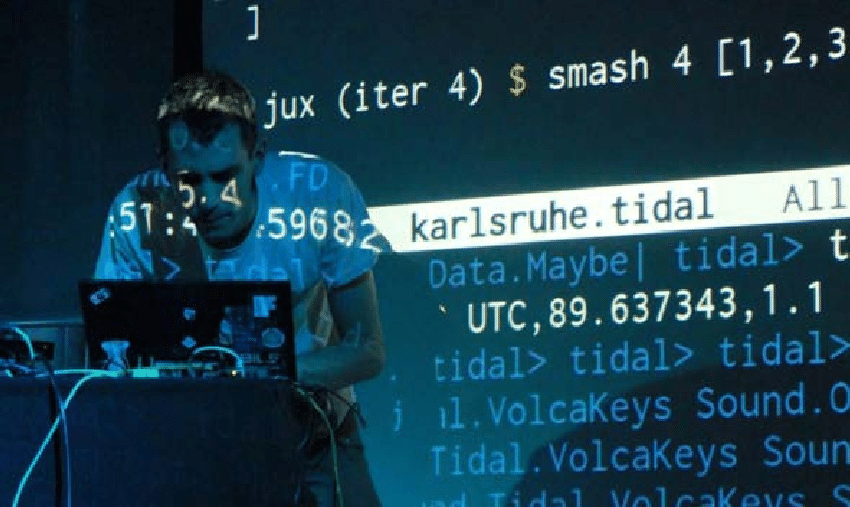

Live coding, Alex McLean (Yaxu) by Rodrigo Velasco

Live coding, Alex McLean (Yaxu) by Rodrigo Velasco

Early visions and developing the practice

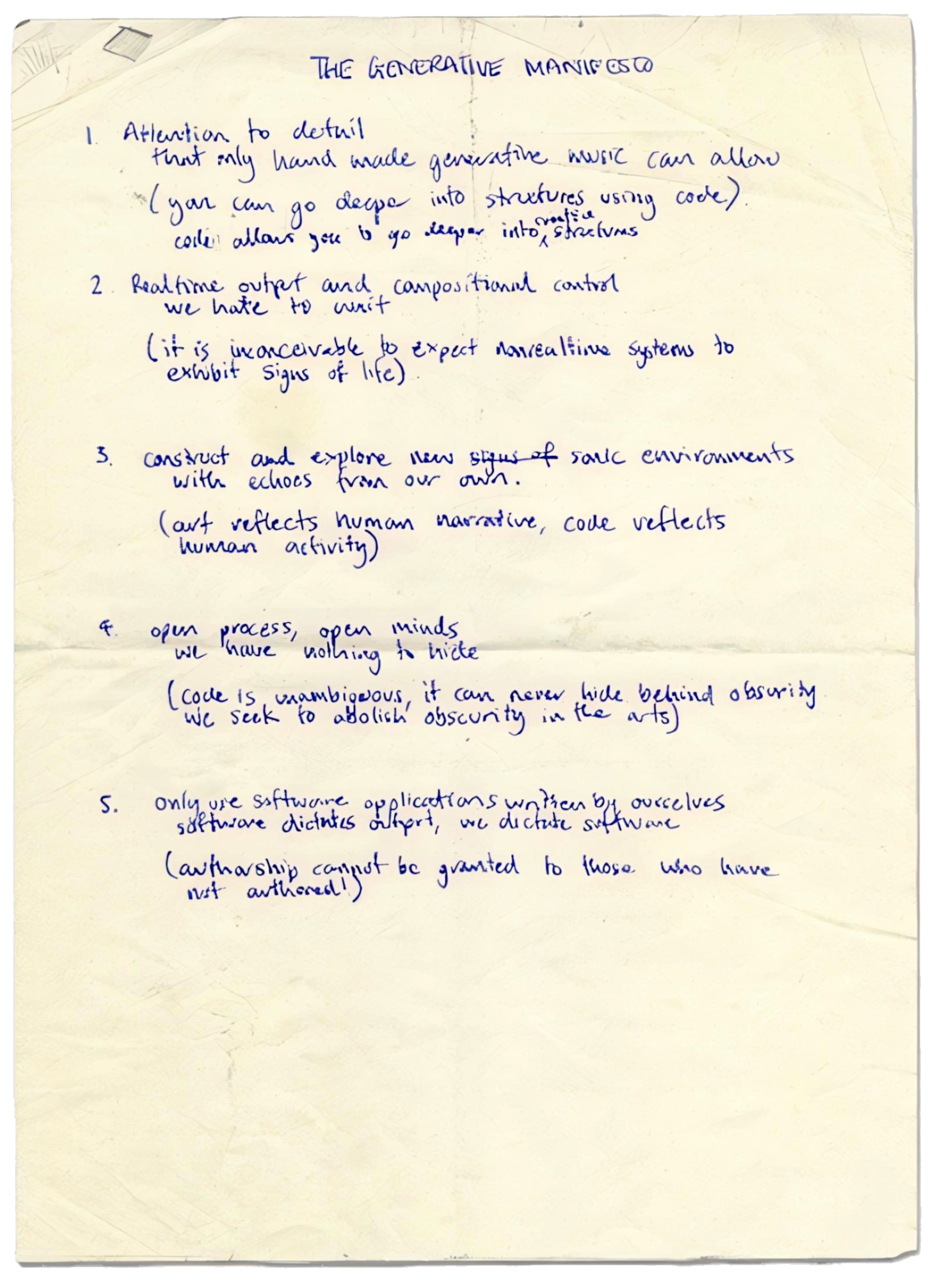

Alex: The starting point for me was working with my friend Adrian Ward, and we started by discussing what we were doing, and made a little manifesto, the “Generative Manifesto” [August 2000]. August 2000: The dot-com boom had burst months earlier (March), but open-source movements continued to gain momentum, while tools like Flash and Java made multimedia more accessible to creators. Algorithmic and generative processes remained largely experimental, confined to academic or artistic niches. And in there, we made this forthright decision to only perform using our own tools.

Justin: Was that manifesto a reaction to an established way of doing things?

Alex: Yeah, I guess it was … a reaction to the idea of programmers being people who do things for other people. In the year 2000, there wasn't an idea of creative coding, there was things like the Computer Art Society in London The Computer Arts Society (CAS), founded in 1968 to advance computational creativity in the arts, had waned by the 1980s. Its decline coincided with the rise of personal computing and commercial software, which prioritised profit over experimental art-tech practices. During its initial run, CAS fostered path-breaking work — including the multi-disciplinary Event One exhibition (1969) and avant-garde journal., but they were dormant, and everything was taken over by the first internet boom.

Alex: So, yeah, there wasn't a creative coding scene there, but we were getting into generative art and generative music, and wanted to say we're musicians, we're writing code to make our music and, yeah, making everything from scratch was our thing. It wasn't live coding at that point, it became live coding gradually, over a few years. Adrian started live coding without calling it live coding, it was just what he was doing. And then we got in touch with other people, realised other people, there was something in the air, people using interactive programming to make music. Key tools emerging at this time included Max/MSP (1997), Pure Data (1996), and SuperCollider (1996), enabling real-time generative sound and visuals.

Image from TOPLAP001 – A prehistory of live coding

Alex: I was using this language called Perl and making my own editor for that, feedback.pl, that was when I switched to live coding … sometime around the founding of TOPLAP TOPLAP (The (Temporary|Transnational|Terrestrial|Transdimensional) Organisation for the (Promotion|Proliferation|Permanence|Purity) of Live (Algorithm|Audio|Art|Artistic) Programming) was established in 2004 in Hamburg, providing live coding with its first formal manifesto. It's decentralised ethos helped connect practitioners internationally. … that was when there started to be a live coding community, and I wanted to be part of it.

Alex: The key moment for pushing forward the practice into something more improvisatory was working with instrumental musicians. But with my system, it would take too long, really, to make any sound at all.

Justin: Before that, it would be people making things ahead of time?

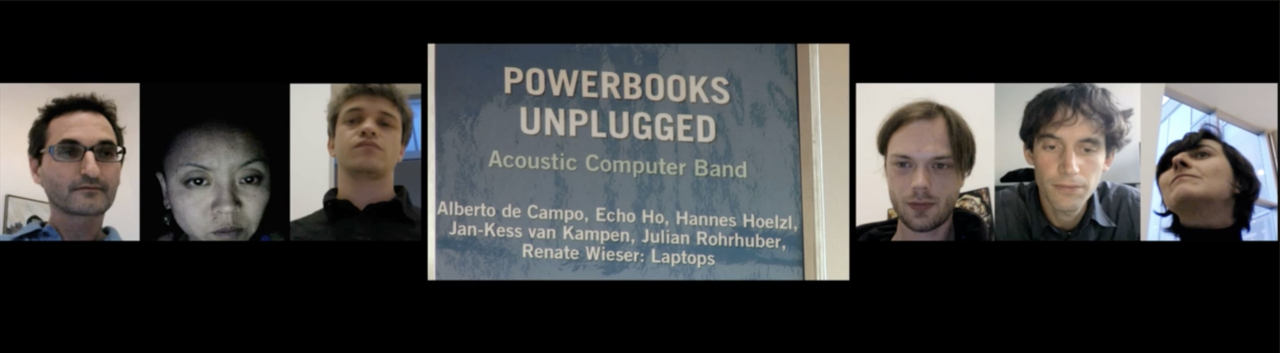

Alex: A mix, I’d say. I think the idea of live coding was to go from scratch, at the start. There weren’t any rules, it was just people experimenting and starting to talk to each other. There was no, like, “this is how you should do this”, because it didn’t exist yet, it was all very plastic. At the start, it was quite radical in trying to break down the distance between performer and audience. There was this band, PowerBooks_UnPlugged, which would have 7–8 people sitting within the audience, using their Mac PowerBook speakers like an acoustic instrument. PowerBooks_UnPlugged were a pioneering ensemble active in early live coding and acoustic computer music. They used their laptops as both instruments and amplifiers, leveraging the PowerBook — a portable, workhorse computer known for its accessibility and versatility, but not its audio fidelity. By embedding themselves among listeners when performing and embracing the limits of the PowerBook’s built-in speakers, they challenged traditional performance norms, fostering a playful collective experience.

Screenshot from PowerBooks_UnPlugged: a patchwork portrait

Screenshot from PowerBooks_UnPlugged: a patchwork portrait

The philosophy of live performance

Justin: I'm interested in the relationship between improvisation and composition, and how live coding relates to that.

Alex: “Improvisation” and “composition” have particular meanings within different musical contexts, and live coding doesn’t fit neatly into these categories. You can think about live coding as live composition, because you’re working with notation, but … you don’t have fixed ideas about what you’re doing. For me, live coding is about listening and deciding when to make changes. This tension between composition and improvisation echoes broader debates in electronic music, but live coding's emphasis on visible process creates distinct possibilities.

Alex: The main way of working with live coding now is by composing pieces, then performing them by manipulating the code. Improvisation, but within the idea of a track that you're performing. But I think the idea of from scratch performance is still much more exciting to me. If I come with a ready prepared piece of code, I don't know what to do with it, because it doesn't feel alive any more … I like the idea of discovering new ideas during the performance and seeing where they go, and getting in that flow state where you’re working with something.

Justin: What's going through your head when you're up there performing?

Alex: I guess the physicality is in the sound … I don’t think about the computer, though having a nice keyboard is helpful. And moving things around on the screen can feel physical, or chopping things up, shrinking them, and deleting them. Putting things next to each other and building these tree-like structures out of code.

What’s in my head? I suppose it is like counting … working up towards the when the next change should be, which tends to be powers of two … working up to that deadline, trying to type, sometimes as fast as possible, so it’s ready to go for that moment when the next change happens…

If I miss that deadline, I might have to wait another two or four repetitions before it feels right to make that change. You’re playing with expectations, and if something changes at the wrong moment, it can feel jarring. It’s similar to cueing records. And I might be trying to think about what to do next, based on whether I want to be more complex, or what to delete, what to take out, what’s been going too long that needs dropping out.

Tools and understanding

Alex: I managed to get on this Masters program in Goldsmiths computing, which turned into a PhD when I wrote Tidal. I was influenced by the Bol Processor The Bol Processor, developed by Bernard Bel, was originally designed to transcribe and analyse tabla rhythms. Its influence on TidalCycles exemplifies how live coding drew inspiration from diverse cultural practices. — originally this environment for notating North Indian tabla. The mini-notation you see in TidalCycles is from that.

Justin: What was Goldsmiths like at that moment in time?

Alex: [The programme] was in psychology, computer science, and music … in a computing department, Goldsmiths' Computing department, established in 2002, was unusual in its interdisciplinary approach, combining technical training with critical thinking about technology's cultural role. but this interdisciplinary mix with loads of interesting visiting speakers, talking about human-computer interaction, spatial cognition, models of creativity, all kinds of things. And just to be paid, a bit, to explore my ideas, felt nice. It meant that I could reflect more on what I was doing.

Justin: When you're making tools, environments, or languages, how do you balance your own needs and use cases with those of the wider community?

Alex: There's something nice about having a community of practice around this thing I'm making. I think the thing I'm enjoying most is when people do something strange and unexpected with the software. But I'm not designing a system for other people, I'm not trying to make a product for other people to use. For the first few years, it was only me who used it. I'd uploaded it to GitHub, a platform for collaborative coding but it wasn't really usable by anyone else.

For me, it's about trying to develop something in isolation but through collaboration with others, making something that's different from what already exists, built on different principles, where you don't know what it is yet. If you're taking loads of feature requests, that limits what it can be, because feature requests tend to be around existing ideas … features from other systems.

Justin: The right balance between openness and being able to fall back, to retreat and do something weird in your own corner for a while … what you’re saying about feature requests being a “straightening” influence is interesting.

Alex: People are used to a certain relationship with commercial software. They're paying for something and they want something in return, whereas with open source free software, it’s more about being in a community of practice. But at the same time, I’ve resisted separate “developer” and “user” channels. I don't want to separate the core development team from the people who use it.

Justin: What does that look like in practice?

Alex: With Tidal, I tried to create this community where stupid questions are encouraged, and no one says, “go and search Google.” Because with every question, there's something interesting behind it. People ask something which they think might be stupid, but it changes how I think about Tidal in certain ways.

Justin: In designing Tidal, you’ve had to balance expressiveness, people being able to express themselves, learnability, and adaptability for performance. Have these been in tension?

Alex: I suppose I find it difficult to tease these things apart. If you make something through the process of using it, it's different from learning it … someone coming to it fresh. I don't have great insights into its learnability, apart from running workshops and finding people get straight into making music within a couple of minutes. I think it's expressive in terms of being able to make a bunch of choices, see what happens, and then respond to it. My favourite performances are where I've learned something new about Tidal, found something new that works. It's part of the sensation of performance, that moment of understanding something by combining different functions in a fresh way.

Conclusions

Justin: Is there anything from live coding that could be brought to bear on more mainstream, problem-focused approaches to software development?

Alex: I guess it's always been there, really, like the idea of command lines and debuggers, but it loses its radical potential if it's used to make something more productive, more efficient.

The kind of software development that aims for seamless use, versus the actual making of it as the end result … they’re something different. It’s interesting, there’s a “live programming” community who are focused on trying to make software development more “live”, faster, more efficient. But theirs is this hylomorphic idea … having this perfect idea that you implement, beaming it into your computer as efficiently as possible. Live coding is more about code as an interface, a way of exploring the world… “Hylomorphic” (from Greek hylē, matter + morphē, form) describes the imposition of pre-conceived structures onto passive matter — a philosophy that live coding actively resists, through its emphasis on emergence and discovery.

Justin: And the audiovisual component sets up particular kinds of feedback loops, where it'd have otherwise been a one-way process?

Alex: With Haskell, a programming language designed for academic and industrial applications, which also provides the foundation of TidalCycles there's this package management system which makes it hard to get a bunch of libraries together and just explore them in the interpreter. And trying to engage with the development community, and talk about how to make it easier to have programming as a user interface, I’ve had a lot of pushback: “Oh no, command-line interpreters are just for utility, they’re not for anything serious” — but “just for utility” is like saying something is “only for use.” They’re dismissing the very thing that makes programming powerful: its utility as an interface for exploring your senses or the world around you. This embrace of programming’s utility — its practical use as a tool for exploration — came alive at a TOPLAP Barcelona event in late 2024. In a dimly-lit independent art space in Poblenou, performers work in randomly-assigned pairs, one creating sound while the other generates visuals in response. The setup is intention: dual screens projected above and below the stage, the performers themselves in shadow, visible only in glimpses as they type. Neither can see the other's code. Yet we in the audience watch both unfold in parallel, an air-gapped dialogue of call and response. The rapid typing, deletions, edits, and moments of hesitation offer intimate windows into their thought processes and decisions. Within the nine-minute “from scratch” constraint, each performance reveals its own internal logic. One pair transforms the Wikipedia article on live coding into a traversable network graph, its structure generating both abstract visuals and an emergent soundscape. Another evokes Cold War hauntology — low engine hums and flickering polygons creating an unstable digital camouflage. The sophistication is clear, but what strikes me is how the audience responds to each attempt — appreciating ambition, experimentation, even when it falters. Between performances, conversations about programming interfaces and conference paper reviews mix with shared pizza and mandatory applause — but casting this as a coding meetup or performance event would be to miss the point. As I watch abstract patterns transform into sound and imagery, the distinction between observers and participants begins to blur. What emerges is what Alex described: a fundamentally different relationship with technology.

Híbrides From Scratch, Barcelona, 2024

By making the creative process visible and open to interpretation, live coding demonstrates how technical practices can be re-imagined as shared explorations. These possibilities emerge precisely because the process itself is open — at once an interface to computation and a window into new forms of technological community.

🜛