Close Encounters with UMAA

Unité Mobile d'Action Artistique (UMAA) as lived experience: lightweight architecture from the inside. Flexible membranes as space-defining skins, lending shape to the air.

Cocky Eek has worked for nearly three decades as a spatial artist and experimental educator, creating large-scale immersive installations. Her practice addresses embodied knowledge and direct material engagement, developing flexible, mobile structures that expand human perception through multisensory experience. Rather than creating static objects, she designs responsive environments where, as she puts it, "we are not moving through space but space is moving through us." This text explores UMAA, her most recent and largest inflatable structure, in relation to its predecessors, Curve (2015) and Sphæræ (2013). Through these (and other) works, Cocky reimagines technology not as rigid or deterministic but breathing, responsive, and alive; qualities permeating this volume's exploration of alternative technological trajectories.

Focusing on Cocky’s direct experiences with inflatable structures, this text includes theoretical annotations by Renske Maria van Dam. Like the 'flying stones' described within – heavy objects that hover paradoxically in space, creating tension and balance – Renske's reflections provide conceptual counterpoints, putting Cocky's embodied knowledge into productive tension with architectural and philosophical theory.

Breathing with UMAA

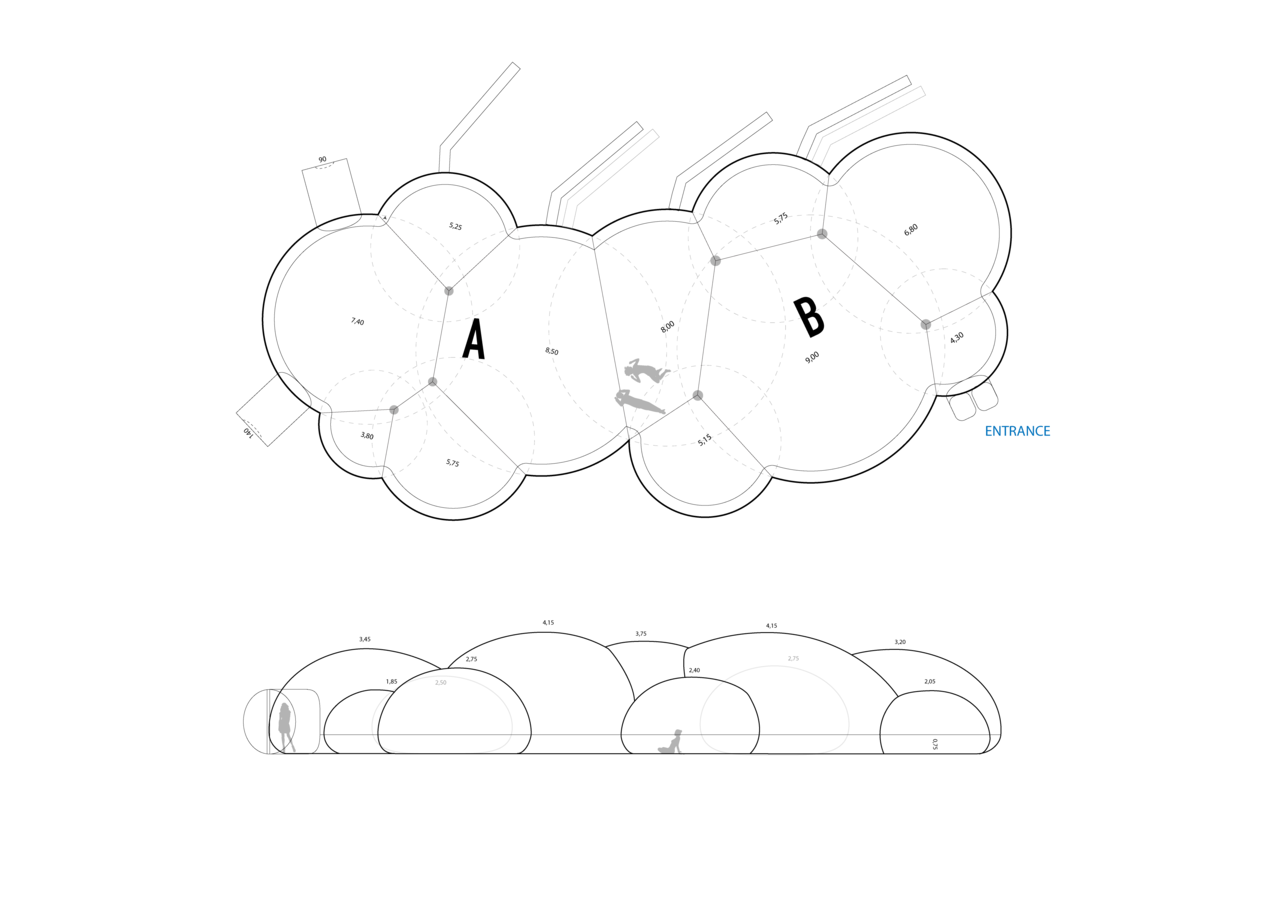

We are enveloped in a breathing structure: on an inhalation the entire structure expands, and on an exhalation the built-up tension releases, the structure relaxes. A constant flow of air enters the low-pressure inflatable multi-dome, becoming a building material that holds up UMAA’s single membrane. Through stitched seams, air escapes back into the world outside. This breathing pattern lends the structure a particular liveliness.

UMAA’s silver cover responds to its surroundings like a living skin: reflecting intense summer heat waves, blocking daylight when needed, and blending the friendly giant seamlessly into any environment, as if it’s not there at all. Designed with surplus material, the rectangular cover drapes nonchalantly over the structure, moving as if on its own impulses when touched by the wind. A light breeze transforms the canvas, creating rippling undulations across its surface. The waves are always different, endless variation within endless sameness. The more that living patterns act upon the structure, the more it comes to life as a whole, the more it glows.

Unlike conventional architecture that separates us from weather and surroundings, UMAA translates environmental forces into new perceptual experiences. This endless variety reveals itself during rain showers, creating an instant listening experience beneath UMAA’s tense overarching skin. One can focus on the polyrhythms of falling droplets or the tiny silences between them. The experience is heightened by the structure’s unexpected acoustics – its ‘whisperdome effect’ carrying whispers from one side of the dome to listeners on the opposite side, as if spoken directly into their ear. Within this acoustic field, my sense of bodily presence shifts; I feel simultaneously here and elsewhere as I hear and feel the falling rain at a distance, my own perceptual boundaries as permeable as the structure’s membrane.

Pulling down the silver cloth reveals UMAA’s internal structure: a multi-dome formation of semi-translucent membrane, spreading a beautiful light I’ve experienced nowhere else. Outside, several giant trees cast their silhouettes onto this luminous skin, creating a marvelous shadow-dance as the wind moves through their branches. This endless variation of light and shadow is a fascinating pattern, connecting interior and exterior in living dialogue.

I hear Cocky asking “UMAA, how are you today?” Rather than acting as a creative genius with a fixed idea, her techniques are processual and immanent, they evolve and reinvent themselves, following the moment of their own unrolling processes. (Erin Manning and Brian Massumi).

Bringing things to life… is a matter not of adding to them a sprinkling of agency but of restoring them to the generative fluxes of the world.

Life is not in the building, but the building is in life.

The structure doesn’t separate us from natural processes, but amplifies and transforms them, bringing us back to life.

Creating spaces where boundaries and categories become fluid and negotiable. Photo by Aurelie Gillson, UMAA, Mille Plateaux, CCN La Rochelle

Conception

In the winter of 2021, while painting our studio wall, I experienced a moment of clarity. Fully absorbed by the repetitive stroking of white paint, suddenly, out of the blue, a clear thought emerged...

There is one more large inflatable structure I need to make.

Two weeks later, I received an email from Patrick Gyger, a curator with a keen interest in experimental arts and immersive environments. Gyger had previously experienced my work firsthand, through “Curve” (2015) – an inflatable tunnel where those who traverse it lose their visual reference points, creating perceptual disorientation and distance from the outside world. He wrote that the choreographer Olivia Grandville was interested in commissioning a traveling inflatable structure that could host up to 200 people for dance performances for Mille Plateaux, a choreographic centre in coastal La Rochelle. Grandville’s choreographic practice, while difficult to describe, explores how bodies reshape and are reshaped by their environments. As director of Mille Plateaux, she has sought to extend dance beyond conventional venues, creating spaces where boundaries between audience and performer become fluid and responsive.)

I hurried to our first meeting, arriving late and flustered, having hastily applied red lipstick only to discover no one else was wearing any. As I wiped it away with my sleeve, Olivia began to describe her fascination with the ephemeral inflatable events of the 1960s-70s. For her, pneuma The ancient Greek concept of breath as both vital force and animating spirit. was the embodiment of a different way of being; an alternative relationship between body and space. As she spoke of her vision for a modular pneumatic structure that would travel through rural France for the next five years, creating temporary spaces where local audiences become active participants, I felt an immediate affinity. We were operating on the same conceptual plane, speaking a common language that transcended English or French. Here was someone who understood inflatables not as static architecture but living environments – fluid, responsive, and alive.

Pliable architecture and the pliable architect(e) co-exist in a double movement.

It is Cocky, it is UMAA.

She listens, she dwells, she abides, she weighs densities, measures speeds, modulates permeations, navigates the grain of textures. All the time, mapping, measuring, naming, finding sense, analysing elements of the place. [...] And with time, abiding in the dwelling with sustained attunement, she finds the place in her body, as her body is in the place.

Choreographing Light and Darkness

Manege Daatselaar, Eemnes, NL, 14 June 2022

In the expansive flatness of the Eempolder – where I first developed my relationship with wind – we gathered to test UMAA's conceptual foundations. Here, at a horse stable under open skies, we arranged a meeting between Olivia's choreographic vision and Sphæræ, my earlier inflatable pavilion. Sphæræ (2013) is an inflatable, immersive, multi-dome environment. Its soap-bubble-inspired architecture created unique acoustic and visual conditions that transformed perception. For over five years, this mobile pavilion traveled throughout Europe, hosting performances and installations that explored light, sound, and movement.

Inside the darkened dome, artists Evelina Domnitch and Dmitri Gelfand performed their piece "10000 Peacock Feathers in Foaming Acid”, using laser light to scan soap bubble surfaces. The focused beam generated immersive projections across the structure’s inner surface, transforming microscopic interactions into vast audiovisual landscapes. Meanwhile, their Belarussian friend Ales Los sat quietly nearby, his hurdy-gurdy weaving a beautiful melodic thread through the electronic soundscape.

Outside, the horses grew curious, drawing closer, their ears perked and noses directed to this strange presence. A sign that we were on the right path, our inflatable environment resonating beyond human perception and interest alone.

Then, the moment that bridged Sphæræ and UMAA. Sitting in complete darkness, our eyes fully adapted to the absence of light, patches of brightness began to appear across the membrane, without explanation. The mechanism was impossible to discern from within – the structure itself seemed to be generating light, as if from nowhere.

Olivia moved outside, intuitively understanding the structure’s potential. She began manipulating the blackout cover – raising its edges to allow small glimpses of daylight, then, with two students, pulling one entire side away… Inside, a long strip of white light appears along the floor’s edge, slowly growing upwards into a screen of white light that climbed the curves of the vault. The giant cloth hangs for a moment, suspended, before sliding to the ground. We find ourselves enveloped in blinding whiteness. The world shifts. More than a simple technical adjustment, this is composition, dramaturgy, scenography – a quality without a name. There is a central quality which is the root criterion of life and spirit in a man, a town, a building, or a wilderness. This quality is objective and precise, but it cannot be named.

As our vision readjusts, we stand in silence, looking into each other’s eyes. I thought that my experiments with this kind of inflatable structure were done by now, with dozens of artists having already explored the possibilities. But this day gave me clear feedback that the experiment with this structure was not over – not yet.

What emerged in that moment – the transition from darkness to blinding light – revealed that these structures were evolving organisms, not finished experiments. Olivia understood that the membrane itself could itself be choreographed, its responsiveness to touch, light, and movement generating entirely new experiences. This realisation was essential to UMAA's conception – not merely a venue for performances, but a choreographic entity that breathes, responds, and participates.

Our moving bodies and environment mutually form and extend each other. There is an intrinsic relation between matter and manner, structure and movement. The felt, experienced surface of Cocky’s architecture and the abstract surface of perception… are two facets of the same topological figureBrian Massumi.

Her raw material should not be thought of as form but as deformation. New patterns of bodily perception and action emerge in the moment of movement, from which alternative experiences inevitably form.

Everything clicked. Within days, I had developed a comprehensive framework for UMAA: not just technical specifications, but a complete system for bringing this breathing architecture to life across south-west France. What began as a moment of clarity while painting my studio wall was now becoming a new spatial composition; one that would continue Sphæræ's exploration of air as material while opening new possibilities for movement and choreography.

Photo by Alain Mascaro

Photo by Alain Mascaro

Emergence and Equilibrium

Saint-Saturin-du-Bois, 21-25 October 2023

It had rained all night and there was no electricity. A vast expanse of fabric lies on the sodden ground, stretched flat, rainwater pooling in its ripples and folds. The blowers activate. I know this is the moment. I slip beneath the fabric, crawling on my belly towards the centre of the cloth, where I wait.

Slowly but surely, the veil begins to lift from the ground. I can see the legs of two young men in the other compartment, working from within to help the fabric rise into its volume. As the structure gathers volume, the wind finds its opportunity, catching the fabric, which becomes the sails on a ship at sea. The men must act now, moving quickly, with a practiced urgency, to anchor the flapping structure to the ground. Observing this scene, I catch myself thinking – this is it, the quality of being alive.

UMAA is not a static venue, but a breathing entity, always a little unpredictable in its behaviour. A sailing ship in need of a skipper, someone who knows exactly when and how to tighten or unfurl the sails.

This dance with environmental forces reveals something fundamental about how technology actually works – not as fixed systems that just work, but ongoing negotiations between human intention, materials, and the wider surroundings, continuing long after the structure takes shape.

To maintain their balance, UMAA’s vaults require their own negotiation with gravity. Where traditional stone vaults rely on pillars pushing upward from below, our inflatable requires downward-pulling forces. This is accomplished with heavy stones suspended by ropes from the lowest points of each dome. The result is mesmerising; seven round white stones hover just above the floor, within the pure white space – lightness anchored by flying stones. For now.

A sudden gust catches the structure. Phwoeff-phwoeff. My eyes widen – oh my god – UMAA rises higher than intended, the result of our modified anchoring system. I have to rely on our giant “river snake”, a water-filled hose winding along the outer edge, to keep our structure from taking flight.

Perceptual Dialogues

Cognac Jardin Public, 2-7 April 2024

I arrived early evening in the park and peeped into UMAA. Everyone was at dinner, the structure momentarily empty. My eyes scanned the edges – the main anchor points weren’t properly secured, and at these critical junctures, the floor was floating about 70cm approximately 1.5 cubits above the ground, following its own topology rather than our designs. Like all living systems, UMAA was asserting its own logic. Parts of the floor blended into the wall, diverging from the precise measurements of our drawing board plans. My breath caught in my throat.

Despite my worries, the next day, the sun was out, transforming both the experience and its audience. Families spread across the grass under tall trees, while dancers guided by portable speakers activated long lines of movement. Their choreography extended beyond the body, incorporating a passing cloud, swaying branches, circular patterns in the grass. Children couldn’t wait to join in; dogs and even a hopping bird were patched in this expanded choreographic field. Beyond them stood a typical French crêperie, and behind me, UMAA waited, present but invisible in the landscape. The queues forming outside were long, people waiting patiently … nobody knows what this is … no reference … nothing …

Photo by Aurelie Gillson, UMAA, Mille Plateaux, CCN La Rochelle

At the entrance a host guided each person to slide in, one by one. The experience was strange and exciting – you had to bend, pressing yourself between two membranes that hugged your body tight, all without any visual reference. How many steps do I have to take? Where will these take me? With nothing but curiosity motivating you to keep moving, your body straightens as you emerge into a voluminous soap bubble formation, your lungs expanding to match the structure’s height. The varying sizes of the vaults create a dynamic topography overhead. The lower spaces feel intimate; the higher more formal. Inspired by planetary forms, the vaults are slightly flattened at the top, giving a subtle sense of spinning. As everything is white, visitors experience a Ganzfeld effect A perceptual phenomenon where the brain, deprived of structured visual input, begins generating its own patterns and sensations. , leaving them disoriented.

UMAA’s single membrane remains porous and fluid – a passing cloud instantly registers as a shift in colour and temperature; a bird’s song outside becomes sound inside. The kids move in sync with the dancers. The boundary between outside and inside softens; sounds from within reaching ears outside. The lady running the crêperie sits beside me, whispering: “I just left everything to my husband – I needed to be here.”

Video documentation from UMAA's first public presentation captures these moments of collective discovery – the tentative first steps and gradual choreography as visitors learn to inhabit an unfamiliar space.

People walk over the ‘non-edges’ where walls become floor, their footsteps making the entire structure dance in response. With each step, you can’t predict how deeply your foot might sink, while simultaneously setting the whole structure in motion. The entrances accumulate traces – dirt from shoes that didn’t know how to enter such a space, worn paths along the non-edges – residues that begin to give UMAA a character beyond our designs. Evidence of human passage and adjustment to this unfamiliar space, slowly teaching the structure – and us – how it wants to be used.

🜛