Knowing When (Not) to Interfere

Fieldnotes from the Island of Seili; Including Observations by the Authors and their Instruments; raw Data from Sketchbooks and Spreadsheets; and a sonic Translation of the Experience.

With excerpts from Spectres in Change Fieldnotes #1 and #2, and scattered scribblings made during the authors’ residency on the island.

June 2017

Seili, a tiny island in the Archipelago Sea. The island is a geologically young and interconnected ecosystem, historically laden with accounts of illness, death, and isolation. It seems serene and benign yet harbours hidden disturbances, spectral hostilities. Plagues of ticks and microplastics overlaid with psychic memories of the oppressed and abandoned. Ecological monsters and anomalies hover on the edges of human perception, cunningly invasive even to a casual visitor.

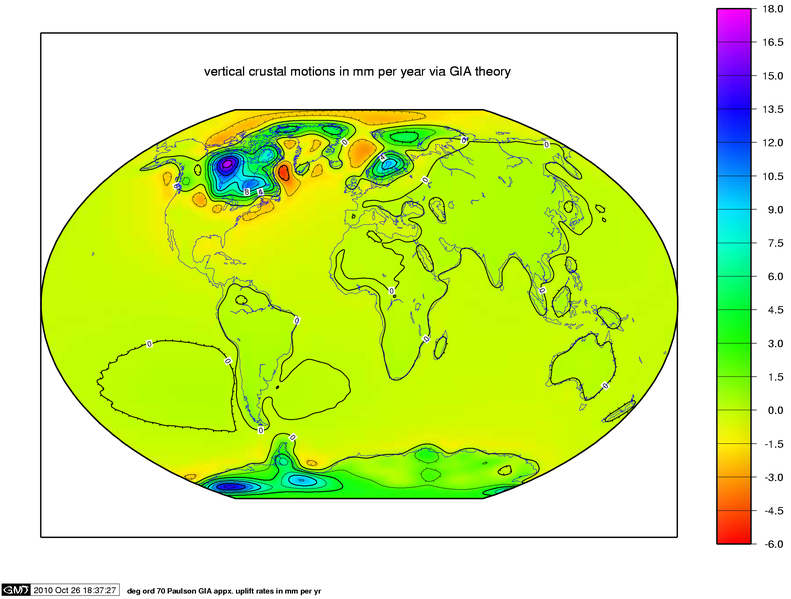

A haunted island covered by soft green mosses, lapped by gentle brackish waves. The sea is sparsely populated with dwindling biodiversity, beset with its own “ecological ghosts of oceans past.” Pincelli Hull, Simon Darroch and Douglas Erwin. Rarity in mass extinctions and the future of ecosystems. doi: 10.1038/nature16160 The island bides in silence, weathering the changing weather. The landscape is on its way to becoming something else, without resistance. Things come, interfere for a while, and eventually go. Sail away, disappear, or die out. Other things remain, as ambivalent hosts or liminal lingerings… Real but not necessarily physical, real but not always measurable. Whether invaded by crabs, humans, or ticks, the island continues its slow and steady rise above the shallow waters, unperturbed.

Rate of lithospheric uplift due to post glacial rebound (in Inference of mantle viscosity from GRACE and relative sea level data. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2007.03556.x

Its inhabitants are but a flickering in the lifespan of the island. The biological time of generations intersects with the slow time of tectonic forces. Fluttering, struggle, change, fragility, and adaptation in a micro-zone of intensity. Too quick to notice while circumnavigating the island in a few hours, the landscape coaxes the present to elongate, to stretch over its quivering layer of events. Lives flickering in and out of existence. Thousands of parasites, the incessant buzz. Swarms of minuscule predatory crustaceans disrupting the delicate balance of trophic interactions. The quickness of this fluttering forms patterns observable over longer periods of time. It demands patience. It calls for knowledge accumulated through repetition, a trance-like noticing over decades and centuries.

The patient can uncover the patterns of interference and disturbance in the seemingly tame landscape. The patient scientist collecting data in ongoing time-series; the patient artist observing the world through time-lapse photography; the patient physician listening to diseased whispers in medical seances; the buried patients, transported to the island to live and die in this confined space without possibility of escape. The sociality of the island used to pulse in and out of sync with the rest of the world. Until winter would come, when cars drive across the sea and lunatics can walk on water… Yet the winters are beginning to change. The ice cracks or shies away from the sea altogether. Rain decreases its salinity. Species migrate as the lively sea erodes into a marine desert. This is observed, noted, and communicated, yet who still cares? Will anyone remain to care?

Time Series (via ARI / Katja Mäkinen)- Tick_data_2012_2018

- Zooplankton abund 1991-2014

- macro butterflies

- odas 2011 and 2012

- seili bird_data 1981-2018 vuosiyhteenvedot

- zoopl_paev 1966-1985

- zooplankton data 1967-2013

- weather data 2011 - 2016

- Säädatat 27.8.2011 - 31.12.2015

-

herring data:

- Fat_Data

- Fat_DryWt_Food_Larvae

- Food_Data_Adults

- Food_Data_Larvae

- Menetelmät ja datakuvaukset

- Trapnet_Samples

- Trawl_samples

Is the mere act of observing an act of caring? How can this noticing, witnessing and recording become a transformative, reanimating force, something beyond representation? A noticing that frames spectral existence with real possibilities and propositions. Abstract data become tactile sensations, beckoning rather than elucidating. Could we think of fieldwork as a careful engagement reminiscent of Ampére’s “tâtonnement”, a “feeling around” the landscape? Devising instruments to lightly brush against ecological transformations, allowing us to touch and be touched by them. Perhaps we would design observatories where layered times can be sensed at a human scale. A collective experience hovering between the spectral and the material. Or conjure a process of environmental interference where art forms compost. A ritual aspiring to express what has been, be present with what is and shape what might become. An experiment in knowing when (not) to interfere.

Our world is now malfunctioning sufficiently for us to begin to glimpse the darker, weirder malfunctioning — the sinister mal that might be intrinsic to functioning as such. Spectrality is the mal of this functioning, not just a superficial appearance, but exactly the sound of extinction faintly audible behind the din of the motorcars, its incredible weakness a horrible symptom of its colossal power.

—Timothy Morton

May 2019

We landed on Seili with the intention of becoming more familiar with the phenomena on the island. We came to explore its environmental and social processes, to observe their implications without immediately confirming or rejecting any hypotheses. In stillness and motion, we observed the porousness between inner sensations and external influences. Between our biology and technology. Between studies, stories, and experiences. Aware of the effects the environment was having on us and vice versa.

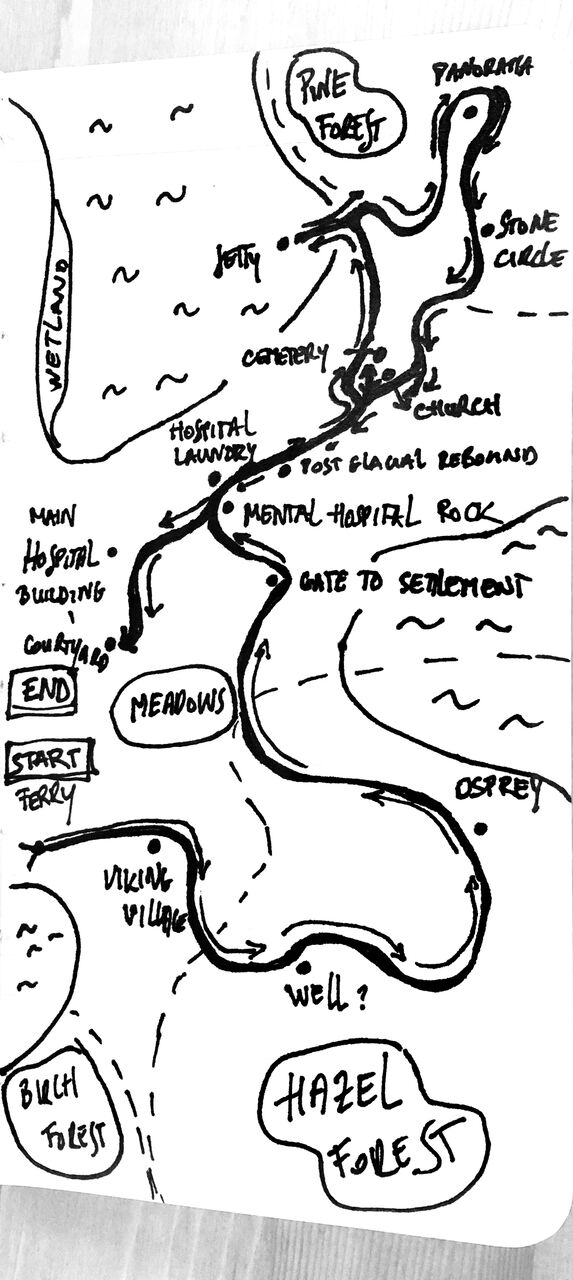

Walking the soundwalk

Walking the soundwalk

We listened to the island and its inhabitants. The longer we listened, the more intricate details of Seili’s soundscape emerged. Tiny fluctuations in the melody or pitch of birdsong in different parts of the island or different times of the day. The many different sounds of flight. From the low frequencies of swans' laboured takeoff to the busy fluttering of songbirds, the buzz of insects and the percussive compositions of flocks of geese. At night, the hushed atmosphere was occasionally interrupted by loud calls or discordant rustling of the nocturnal animals — moths, dogs, deer, badgers. A polyphony of rhythms and overlapping sounds. The quieting after sunset never becoming completely still. The hum of human activity always present as background radiation. Motorised boats of all sizes, fridges and heaters, aeroplanes and quad bikes, drones and transport carts, the Eurovision Song Contest and Saturday night techno.

To hear the smaller, quieter voices of the island we resorted to a technological augmentation of our senses. We could pick up a range of vibrations through the air, rocks, or anthills. Yet, the biological and geological scales that drew our curiosity remained mute to human ears. With the help of microphones and digital sensors, we began to hear unseen life in the undergrowth, between reeds and in the trees. Our instruments let us listen to the island across wider spatial and temporal scales.

We sat on rocks and walked through forests, watching the interplay of sunlight and clouds of swarming midges. At dawn and dusk, light and colour drifted in slow transitions. The long hours of daylight coaxed out the viridian green of spring growth. Even the minuscule cracks between the rocks sprouted green. The foliage and flowering plants became more lush with every sunrise. Meadows changed colour as different flowers began to bloom. Gradients of blues, purples, yellows, and whites. Moss and lichen drying. Brittle, greying, and subdued in the unseasonal drought. Over time, the island has become more prominently dissected between public areas and private property. The space for science and space for leisure. Summer houses and private jetties. The “hordes” of tourists seemed at odds with the scientists' concern for (relatively) controlled ecological experiments.

The scents of the island changed over the week from the bitter green herbs of early spring to pollen-heavy sweet smells of flowering trees and bushes. Yet the base notes of specific habitats remained. On the south of the island, the scent of the hazel forest was fresh, musky and herbaceous, while the pine forest of the north was more resinous and dry. The coast smelled swampy, decaying plant matter with a salty tinge of brackish water. The middle of the island was mostly scented by humans. Dust and compost mixed with the floral notes of ornamental shrubs, entwined with smoke and the heavy smell of cooking.

Tasting Seili, on the menu:

Sautéd pine tips with Finnish grilled cheese

Wild allium and oat cream risotto

Porridge with cowslip and strawberry coulis

Wood sorrel lemonade

We sought out food that could be foraged on the island to enhance our meals. The abundant “viking leek” (allium schorodoprasum) and wild chives (allium schoenoprasum) became prominent in our savoury dishes. Pine tips, nettles, wood sorrel, ramson, and dandelion tantalised the palate with their bitter, tangy, and pungent flavours. We created new recipes each day, spurred on by our otherwise frugal food supplies.

It might seem indulgent or pointless to spend time attuning to an environment when circumstances demand urgent change. Yet taking time to attune to the effects of environmental turbulence can motivate more engaged action. An intimate connection to a place can provide more suitable methods and lasting results. Well meaning but inappropriate action can sometimes be more detrimental than doing nothing. In some cases, when “fixing” something becomes impossible, a palliative “being with” a changing landscape can be the most appropriate act of care. In other cases, caring requires immediate and direct action (for example, preventing the clear-cutting of a forest).

How to gain permission or invitation to act when no explicit communication or consent is possible? Discerning how to be and what to do in an environment requires careful protocols of engagement. From understanding the gradient of consumption (for example, how much can we eat without causing harm), to negotiating various instances of give and take, we may need new rituals to re-familiarise ourselves with being in other-than-human contexts. We may need times, places, feasts, or talismans to focus intent, to evoke and invoke the spirit of reciprocal relationships with a place and all who dwell in it. But to begin with, sitting quietly is a good start.

Exercises in Attentiveness

❧