Plant Guilds and Earth Dumplings

And Other Examples of FoAM’s Gardening Practices.

With excerpts from groWorld: Experiments in Vegetal Culture and Seedballs.

Plants work together with other plants, fungi, bacteria, humans, and other animals to generate a thriving ecosystem in a garden. A gardener creates or facilitates conditions for this collaboration to happen, without being in control of the processes or the outcomes. Rather than focusing on single, one-off interventions, gardening requires developing a long-term relationship with living systems. The tools used to cultivate, monitor, and maintain a garden form a part of this ecosystem. From the earliest digging sticks to AI assisted apps, working with hardware and software can augment human capacities to sense, learn, and intervene in complex processes of growth and decay.

Ecosystem gardening and permaculture contribute to the coexistence and well-being of its many inhabitants, including humans. Even if it isn’t feasible for each of us to address the concerns of dwindling biodiversity and food security on a global scale, gardening an ecosystem (back) to health can be physically and emotionally beneficial for all involved. No matter its scale, a garden can be conducive to better food and air, as well as joy, solace, and insight.

Montepreti beehives, Anna Maria Orru

Montepreti beehives, Anna Maria Orru

The ultimate goal of farming is not the growing of crops but the cultivation and perfection of human beings.

—Masanobu Fukuoka, The One Straw Revolution: An Introduction to Natural Farming.

Companion planting on a rooftop garden, FoAM Brussels

Companion planting on a rooftop garden, FoAM Brussels

MidWest Experimental Station, FoAM Amsterdam

MidWest Experimental Station, FoAM Amsterdam

Regeneration of a church garden, FoAM Amsterdam

Regeneration of a church garden, FoAM Amsterdam

While some of us have access to land, those living in cities can practice ecosystem gardening in a jar, on a windowsill, on a balcony or a rooftop. Urban gardening doesn’t stop at fenced-off backyards and allotments; it can cultivate continuous green passages across unused, abandoned or neglected public spaces. Tiny gardens can pop up in gutters and cracked pavements, as stepping stones to parks and community gardens. No space is too small or too far from the ground. It is never too early or too late to garden a small world into being. It makes a difference, one plant at a time. This is how we came to be interested in urban ecosystem gardening at FoAM in Brussels and Amsterdam. By exploring how to design minimum viable ecosystems, we embraced permaculture guilds, and on an even smaller scale, seedballs.

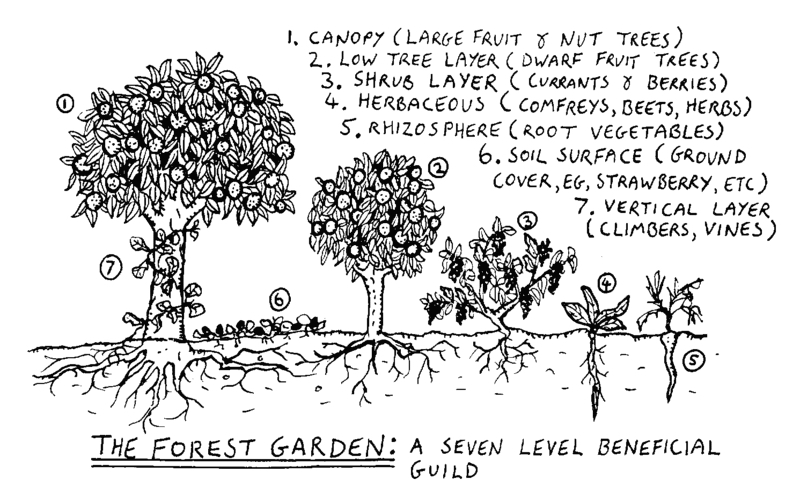

Permaculture guilds are polycultures, collections of plants that grow well together. One of the ancient examples is the Iroquois nations’ “Three Sisters” interplanting of corn, beans, and squash where each plant contributes to the mutual benefit of all three. In contrast to monoculture farming, companion planting and permaculture guilds are examples of gardening with multi-species collaboration in mind. Plants whose characteristics can help each other grow are cultivated together. Some of them fertilise and extract essential nutrients from the soil; others’ roots pull water from deeper layers underground. Some provide shade and support. Some attract pollinators or repel pests. Over time, these multi-species collaborations can grow into self-sustaining habitats able to feed humans and other species alike. No additional pesticides or fertilisers required. Guild gardening is advantageous in urban settings, where we tend to grow a variety of species in small spaces and need to keep scarce soil fertile.

Three Sisters By Anna Juchnowicz

Three Sisters By Anna Juchnowicz

An extremely compact form of companion planting are seedballs, also known as seedbombs or earth dumplings. Seedballs contain an embryonic ecosystem on the scale of a ping-pong ball. They contain a mixture of red or brown clay, vegetal compost, and a carefully picked collection of seeds. The composition of seeds depends on the gardeners, beneficial interaction between the plants, and the position and condition of the site. Some seedballs can grow into food forests, some into wildflower pastures; others are used for reforestation and regeneration. FoAM’s seedballs often contain seeds for “weedscapes” of native plants: able to replenish and purify the soil in urban and industrial zones, and edible for urban dwellers — humans or other animals. Throwing seedballs does not require digging, which makes them perfect vehicles for guerilla gardening in cities, where tilling is not an option. Seed-bombing while walking, biking or driving. Gardening on the move.

Dispersing groWorld seedballs in Adelaide, Australia in 2004

Dispersing groWorld seedballs in Adelaide, Australia in 2004

Make your own seedballs

Excerpts from Seedballs (土団子,土だんご, Tsuchi Dango Earth Dumpling)

A natural farming technique developed by Masanobu Fukuoka, and loved by children everywhere. This recipe is adapted for FoAM’s urban gardening on neglected or abandoned public spaces in or near cities.

Ingredients

- Dry compost (3 parts)

- Dry red clay in powder, sifted (5 parts)

- Dry seed mixture (1 part)

- Water (1-2 parts, depending on the mixture)

Method

Coat the seeds with dry compost, then clay. Add water, a little bit at a time, until the mass is easily “kneadable”. Form small balls (1~2 cm) and leave them to dry for about 2 days. Spread in the city by throwing onto unused lots, parks, next to canals or rivers.

What seeds should I use?

This depends on for what purpose you're using the seedballs. For a small ecosystem in one ball, choose a mixture of 2-3 grasses, 2-3 flowering plants, 2-3 shrubs, 1-2 ground covers (clover is an excellent nitrogen fixer), 1-2 bushes, and 1-2 small trees that can form a plant guild. Preferably look for seeds that are endangered, edible by humans/animals, loved by bees and butterflies, good for keeping water levels appropriate for other plants, able to control pests and purify air, and not invasive. If you are planning to throw balls onto roofs or close to buildings avoid trees and bushes, as well as plants with deep roots. Best is to choose plants that can help each other grow, such as companion plants and larger plant guilds.

❧