Mud Futures

Concerning the material properties and worldings of mud, as particles in suspension; beyond rural pasts and formless nature, an exploration of what it now proposes, the futures it elicits or evokes.

‘What of that feeling of toes squelching and squirching in cool mud on a hot summer’s day? What of the damp, moist earth that gardeners work between their fingers? What of the visceral pleasures and delights of formlessness, that intimate stickiness that we embrace, long for, desire?’ (Boon et al., 2018: 38)

‘These men in their forties demonstrate the ways in which each type of mud “opens up” differently to those who know how to hold it in their hands. They carefully drop the mud into my hands to allow me to feel its weight, compactness, and density. They instruct me on how to feel the mud’s smoothness with my fingers, how to perceive its texture by rubbing it in my palm, how to distinguish the ways in which it reflects the light. Although they don’t tell me the difference, with connoisseurs’ gestures, their hands are coaching mine.’ (Cortesi, 2019: 620)

‘We came to meet the mud, not as a thing, but as a material condition.’ (Lutsky and Burkholder, 2017)

Mud bath

In July 2020, the Boryeong Mud Festival takes place online. Launched in 1998 to support the South Korean city’s cosmetics industry, COVID-19 countermeasures see the festival’s organisers rework the annual event from a collective, place-based gathering to something dislocated, virtualised. The host city distributes kits containing mud packs, soaps, and coloured mud powders. A gallery of high-resolution press photos – syndicated by several international publications amid the churn of news stories during that first pandemic summer – show two children lying, belly-up, in a blue and white inflatable mini-pool. Surrounded by pale laminate flooring, the pool’s bottom is obscured by a shallow layer of dark liquid mud, while, in the background, we can see a laptop and flat-screen TV wrapped in protective plastic – displaying a grid of Zoom-boxed faces and footage from a K-pop livestream. More about co-presence and collectivity at a distance: Gathered and Scattered by Dougald Hine

Displaced to a Gwangju apartment, one site among the many implied – and connected – by the on-screen Zoom grid, this atomised, downscaled festival created conditions for mud to be welcomed into the home, invited into a space where it would usually be disavowed as dirt. Speaking to a Reuters interviewer on camera, her face caked with a mud pack, the mother of the depicted children, Kim Young-ah, explains: “My home gets dirty, but the children enjoy it, and I am happy for that as well.” (Reuters, 2020) She welcomes mud for what it indexes and enables: play, enjoyment, an air of normality amid suspended social contact.

For Preeti, a Bihari woman befriended by environmental anthropologist Luisa Cortesi, a similar calculus yields a very different outcome, as she forbids her five children from playing by the nearby river – denying them the opportunity to learn to swim; a life-saving skill. As Cortesi explains:

‘It is not because Preeti is afraid of the river: she also forbids her children to have fun at the local pond, which is almost risk-free. Ponds and rivers are polluted nowadays, she retorts, despite later contradicting herself by stating that she would drink river water. If the children play in the river, or in the pond, they will be considered low caste, she comments. If only low caste children go to the pond, then only low caste children will see her children anyway, I reply. Instead, she acknowledges that people from all castes go to the pond or to the river, but she also points out that the children's clothes will become muddy, and that on the way home, everybody will see them as "dirty children."’ —Luisa Cortesi (Cortesi, 2019: 624)

Where her children see a source of fun, for Preeti, mud represents dirtiness, indexing proximity to (and interactions with) a natural environment devalued in pursuit of development, modernity, and formal education. (Cortesi, 2019: 625)

These two mud baths, fast-flowing river and inflated mini-pool, pose questions about mud as a form of matter with world-defining properties. While both sets of children approach liquid mud with curiousity and playful enthusiasm, Preeti and Kim Young-ah react differently to mud’s meanings. At the dislocated, domesticated mud festival, mud becomes a proxy for a shuttered experience economy, through a scattered emulation of a cherished, place-based live event. For those living on the riverbanks of North Bihar, mud is omnipresent, inescapable, intimately familiar, staining clothes and sticking to the bodies of those ‘walking on a muddy path, playing in quicksand, fishing in a pond’ (Cortesi, 2019: 621). Activities widely perceived as domains of the lower castes and classes. In this second setting, the spectre of mud baths and quicksand threatens a mother’s efforts to preserve her children’s cleanliness, as a visible ‘performance of success.’ (ibid: 624)

Particles in suspension

Mud is a colloidal material, similar in composition (a sibling) to mist, dough, gel, paste, and foam. (Szerszynski, 2022) . Comprising particles in suspension, mud’s behaviour confounds familiar categories of solid and liquid. Presenting as a shifting, formless blend, it can be stretched or compressed, deformed – disrupting the distinction ‘between ... soil and water, fluid and viscose, plastic and robust.’ (Cortesi, 2019: 618)

But as a colloid, mud is not truly formless. Though it may appear to human onlookers as a continuous substance, it is neither one big, continuous ‘blob’, nor a collection of smaller ‘blobs.’ Like other colloids, mud comprises a ‘population of discrete, similar entities surrounded by an enveloping [in this case, liquid] medium’ (Szerszynski, 2022: 146), acting – and interacting – as a ‘braided, dynamic set of correspondences and answerings.’ (ibid: 141)

Mud hut

“Is there equivalency? Do we refer to homes built by very wealthy people in the United States, in Europe, by a type of material used in the construction of their home? We do not. There's no equivalency there, so the reference is fundamentally flawed.” (Cristi Hegranes, CEO of Global Press, cited in Castillo, 2022)

‘in another society, architects would build different buildings, the buildings would represent different things and people would use them differently.’ (Müller and Reichmann, 2015: 223)

The robot’s custom nozzle, its vast machine cloaca, remains stubbornly blocked, despite the application of pressure. Today’s mud will stay unsquirted, unpuddled. Visibly deflated, they go through the motions of reporting the malfunction, as per the terms of their license, but even after they manage to coax the OneWeb receiver online, the supplier’s FAQ offers little additional guidance. A generic help interface delivers them to a chatbot, who funnels them towards a web form. The system crashes and the form goes unsent, the stretched fabric dish pulsing an indignant red, her usually unflappable partner making barbed asides to some imagined audience just out of sight.

She’s not convinced it would have helped, even were the connection to hold. They’ve deviated from the approved vendor, renouncing the cloud to deploy a home-brew design programme, some software contraption conceived by her partner. Seeking a speedier deposition rate, he pushed at the door of the possible, finding a way to overclock their rented robot printer. But this came at a cost: one time in eight, say, the mechanism clogs, forcing them to demount and replace the feed sack, sending them back to the utility hook-up to hose off the mud paste before it hardens to the consistency of rock This is not the promised ‘more accessible, portable, and ecological approach’ to additive architecture offered by a ‘mobile and lightweight, 3D printing set-up’ (San Fratello and Rael) – but something cheaper, fast-moving but inelegant, perpetually on the edge of failure.

Their mud mixture uses wild clays – excavated from a part of the site earmarked for a future amphitheatre – which they bake in a parabolic trough, before sifting out the coarser particles. In-situ resource utilisation, her partner calls it, using NASA terminology; though, as she’s quick to remind him, this is not the moon. These fine clay particles are blended with sand bought in from outside. Once wetted, the resulting mud is leavened with straw fibres, lending strength and durability.

Later, scraping the residue of adulterated wild clays from the printer’s hydrophobic sacking, her grip slips, and she drops the blunted blade. It falls to the ground with a clatter. To think, she’d agreed with those who cast 3D printing as a perturbation, spinning them out into an unimagined latent space. Framing this shift as a rupture, some seized the opportunity to recast traditional materials, such as mud, as ‘sophisticated building materials for the twenty first century’ (San Fratello and Rael) Still new to the field, lacking conviction, she and her contemporaries fell into lockstep, seduced by visions of ‘new, contemporary craft and architectural traditions.’What they got, instead, was a vernacular of the endless horizon and the soils beneath their feet. Anthropologist Marcel Velliga approaches the vernacular as a prelapsarian category for that deemed ‘ancient, natural, honest, and specific to cultural groups and places’ (Vellinga).

Life in the wake of capital-A architecture, her and her partner as endlings of a profession stuck at five minutes to midnight; once rigid, starched, now melting into ooze. Using a rough length of plywood, she continues breaking down the hardened clods gathering in the grated drain.

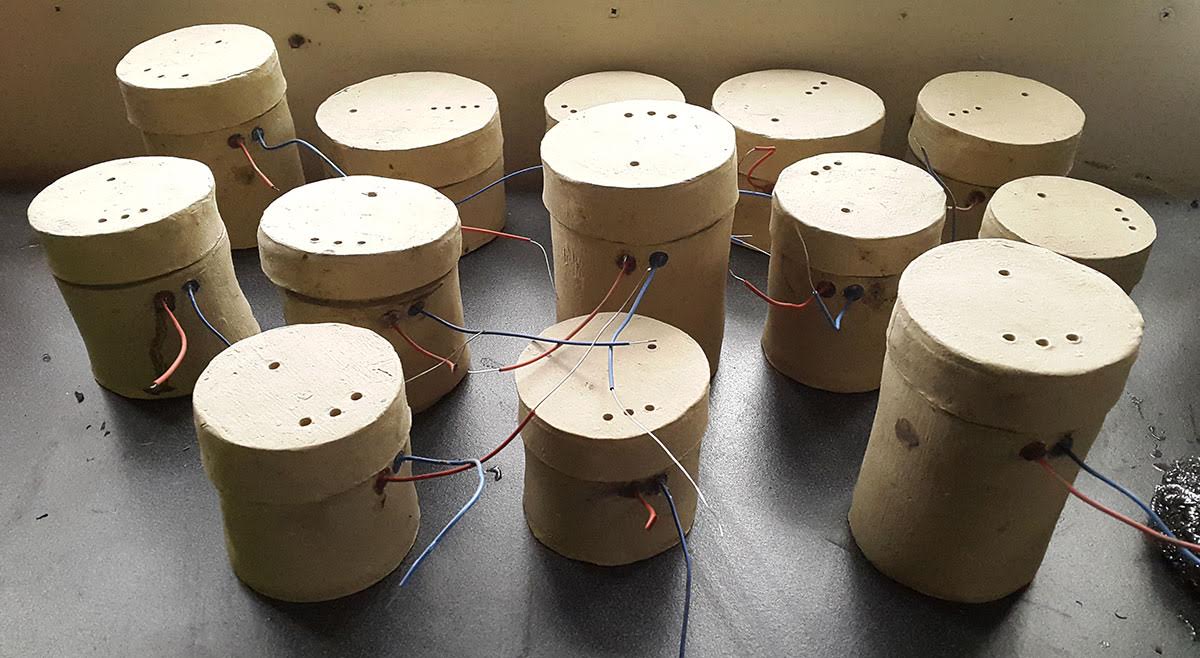

Mud battery

The microbial fuel cells proved messier than any of us expected, spreading gunk and mess through the caravan, no matter how careful I try to be; far from the clean, clinical technical demonstrations we’d seen under harsh strip lights on the convention centre floor. Instead, it’s all tubes and pipes; a knotted mass of leaky plastic tendrils trailing across the floor. In recent weeks, I’ve caught myself ascribing personality to the bacterial biofilm, separate even from the fuel cells; this diligent, obsequious membrane of anaerobic microorganisms, Labrador-like, eager to please, keeping the sensors sensing and the LEDs lit. The cell rigs are simpler, but needy, demanding regular top-ups – and an occasional cycling of contents – to keep the current flowing.

So I head down to the harbour at dusk, this land-water interface, a frothing, foaming coastal line continually reshaped by the ebb and flow of the tides. The mud here is smooth but dark, opaque, revealed by a falling sea. Its smell is both salty and acidic, with a sour note of fermenting fruit. Pulling on boots and rubber gloves over my workwear, and lifting a shovel, I fill buckets with mud from the foreshore; clip-sealed vessels to be cradled in a coiled stained dog towel in the back of the by-the-hour car club rental. I sense their weight, later, from behind the wheel; the near-liquid sloshing, shifting strangely as I brake at the lights. But I’m getting ahead of myself; that’s all still to come. For now, a peace of sorts, among the bait-diggers tracking worm casts with their head lamps, which float and bob at eye level in the settling dark. Our tools might look similar to someone peering in from the outside, but our end goals are radically different, the anglers and I. We are not the same. No carping about trophies or near misses on social media, for me; my solace is the imagined LED glow of a jury-rigged, plastic-bucket prototype, awaiting my return.

Mudded horizons

‘It might seem odd,’ writes design researcher Tom F. Lee, ‘to suggest a substance like sugar’ – or mud – ‘can be world-defining, but history tells us otherwise.’ (Lee, 2021) To fully appreciate this point requires a certain modesty, as the same holds for ‘love, greed, consumers, or a little story about a man from Nazareth.’ Taking and holding mud as our focus, we must consider what this substance proposes; the different worlds it elicits or evokes.

Today, in 2023, mud (still) indexes underdevelopment and the rural. What else could it do? Bath, hut, battery: three ways of using mud; three openings, gestures to future potentials. Encounters with liquid mud in South Korea and Bihar show how similar substances may be experienced differently, prompting divergent emotional and bodily reactions. Spanning high technology, vernacular techniques, and local materials, additive mud construction could catalyse the deskilling and eventual dissolution of the architectural profession. As mud batteries, microbial fuel cells’ lit bulbs and sensing sensors track the microscopic life and material agency of a vital, humming colloidal matter.

There is a ‘troubling opacity to mud, and also an uncomfortable fleshiness’. Boundary-breaching matter, these seeping incursions are signs that stick. Sonja Boon and her colleagues see this clearer than most, describing how, in its basic, elemental composition, ‘mud … resists the very notion of boundaries; this resistance to form is visceral and embodied, and it provokes equally embodied responses.' (Boon et al.)

❧

Further Reading & references can be found in the bibliography.