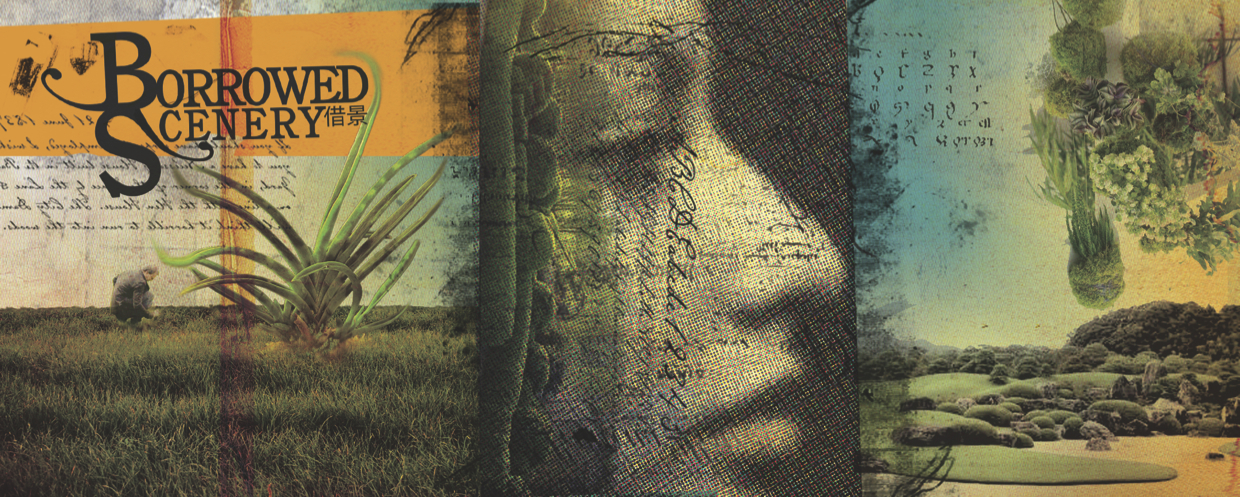

Borrowed Scenery

In Which Gardens, Landscapes, Stories and Songs Entwine into an Alternate Reality Where Plants Are a Central Aspect of Human Society.

With excerpts from groWorld: Experiments in Vegetal Culture, Patabotanist’s Logbook, and In Conversation with Stevie Wishart.We are in the Victoriakas—the historic conservatory of the Ghent botanic gardens—in the last days of autumn, performing Inner Garden, a choral work composed by Stevie Wishart as part of FoAM’s Borrowed Scenery. It is a kind of liturgy to the plant world, imbibed with medieval mystic and composer Hildegard von Bingen’s sense of viriditas, the luminous green force of nature and its cycles of growth and decay.

From various corners of a large overgrown greenhouse come sounds of gurgling and muttering, shrill clicks, hisses and buzzes, then a soft, almost subliminal droning, as though the plants themselves are vocalising their inscrutable thoughts. These sounds gradually condense into words, though apparently not of any familiar language, and are passed around from one end of the greenhouse to the other in an alternating, undulating movement: weaving, reverberating, echoing, then at last merging back together into a sustained, ethereal hum. From out of this murmur soars for a few moments a single voice singing what might be some form of medieval plainchant, before it too subsides into the slowly dying susurrus.

—Alkan Chipperfield

Scalo Aieganz

Dilzio Limix Zizim

Oscilanz Scaurin

Aniziz Diuloz

Scalo = Dawn

Aieganz = Angel

Dilzio = Day

Limix = Light

Zizim = Compass

Oscilanz = October

Scaurin = Night

Aniziz = Soil

Diuloz = Sanctuary

—Coda to Inner Garden (in Hildegard von Bingen’s conlang Lingua Ignota)

An Alternate Reality Narrative

Borrowed Scenery was a story about an alternate reality (past, future, or parallel) where plants are a central aspect of human society. Weaving through the physical spaces of everyday life, the story could be experienced wherever plants and humans interact; parks, windowsills, markets, rooftops, and ditches. Borrowed Scenery encouraged the inhabitants and visitors of Ghent in Belgium to see urban plant life with fresh eyes and reimagine cities as places of sinuous interaction between humans and plants: where plants don’t just provide food and materials but could become cherished neighbours, teachers, and gateways to the planetary “Other”. In the story, humans borrow (attributes, metaphors, characteristics, interactions, approaches to collectivity and introspection) from the vegetal to reinvigorate urban culture amid the Sixth Mass Extinction.

Borrowed scenery held up a magnifying glass to reveal vegetation where we would usually overlook it: in cracks between buildings, on our plates, in emerging technologies and age-old stories. While in consensus reality humans cultivate plants (or so we think), in Borrowed Scenery plants cultivate humans and absorb human culture into their growth and form.

The intention of Borrowed Scenery was to explore the edges between nature and culture; gardening and engineering, borrowing partial descriptions from the languages of mysticism, science and science fiction. It was an invocation, a story that wanted to become reality. By borrowing the setting (or scenery) of everyday life in the city, it infused habitual urban activities—such as walking or eating—with a vision of a possible future where insatiable economic growth is superseded by an atmosphere-based economy, where nature has a voice.

Borrowed Scenery by FoAM on Vimeo.

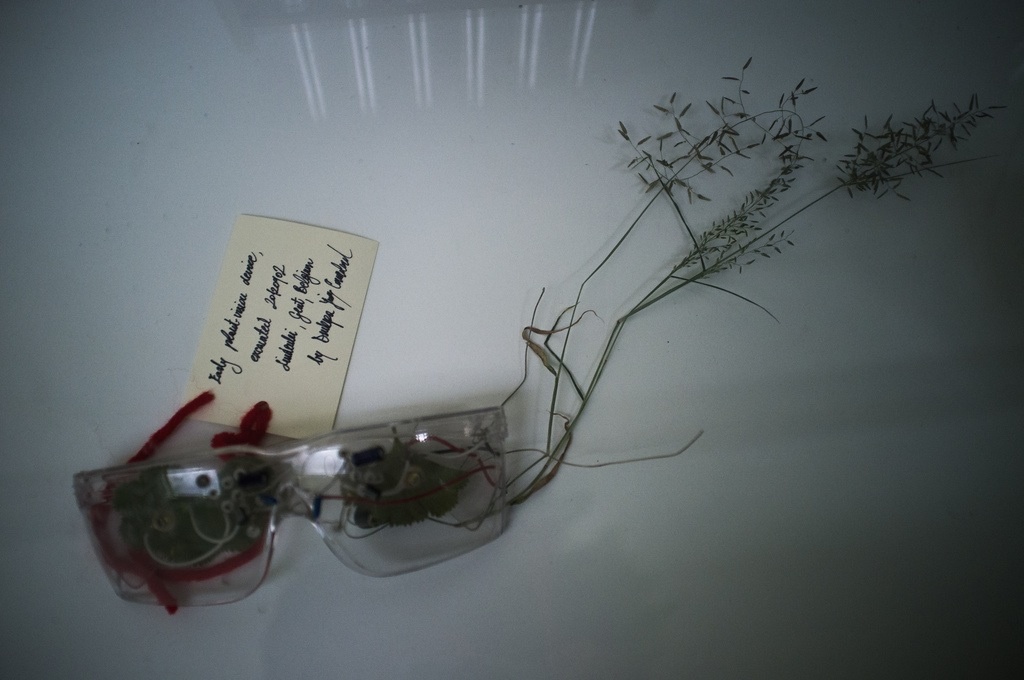

I distill my potion beside forest pools in the first light of dawn, under the slowly sinking silvery moon of late summer. In these forests I collect wild verbena and lady’s mantle, which grow in the hidden dells and culverts where falling droplets of moonlight congeal. These droplets of alchemical moon water can be preserved using a delicate crystalline apparatus. At a moment just after the false dawn, when the coolest, palest colour of the day filters through the leaves of the forest, I infuse these droplets with scents that are condensations of dreams and memories, and mingle them with the volatile essences of verbena; then my potion is almost complete. I prepare another vial of concentrated morning dew, condensed from the twilight mists of the forest just before dawn. Served in the right way, I hope that these substances can imbue the thoughts of those who take them with inner landscapes.

Two drops of the potion are dripped onto a lady’s mantle leaf held in the cupped hand of the drinker. (These leaves must be folded into the protective pages of a book made from ancient parchment, to preserve their sustaining properties.) At the same time as the potion is drunk, the elixir of concentrated morning dew must be sprayed in a fine mist above the drinker’s head. Those who partake of these substances will catch a fleeting but piquant vision — an awakening landscape of viriditas.

Two drops of the potion are dripped onto a lady’s mantle leaf held in the cupped hand of the drinker. (These leaves must be folded into the protective pages of a book made from ancient parchment, to preserve their sustaining properties.) At the same time as the potion is drunk, the elixir of concentrated morning dew must be sprayed in a fine mist above the drinker’s head. Those who partake of these substances will catch a fleeting but piquant vision — an awakening landscape of viriditas.

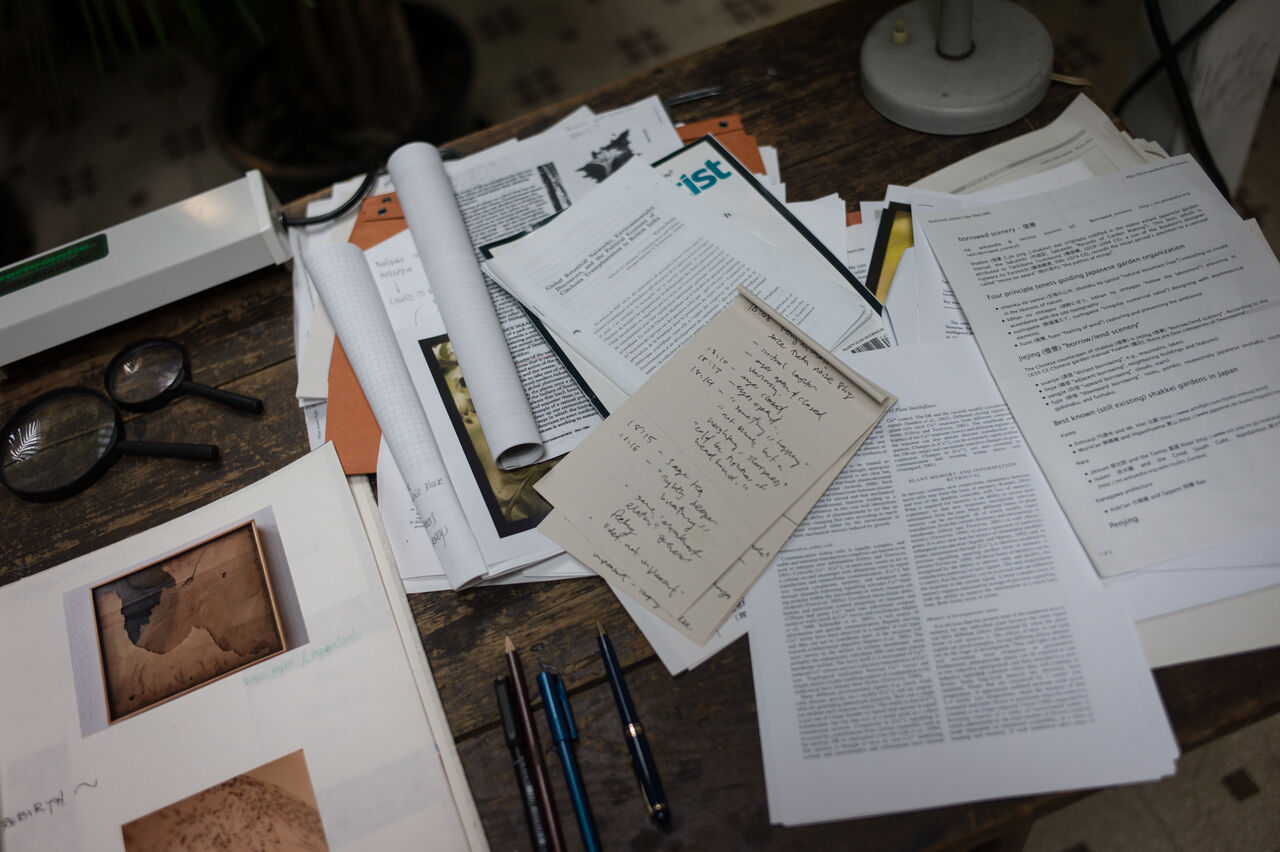

—Alchumilla Umiliata. Excerpt from the chief patabotanists’ logbook

Contemplative Horticulture

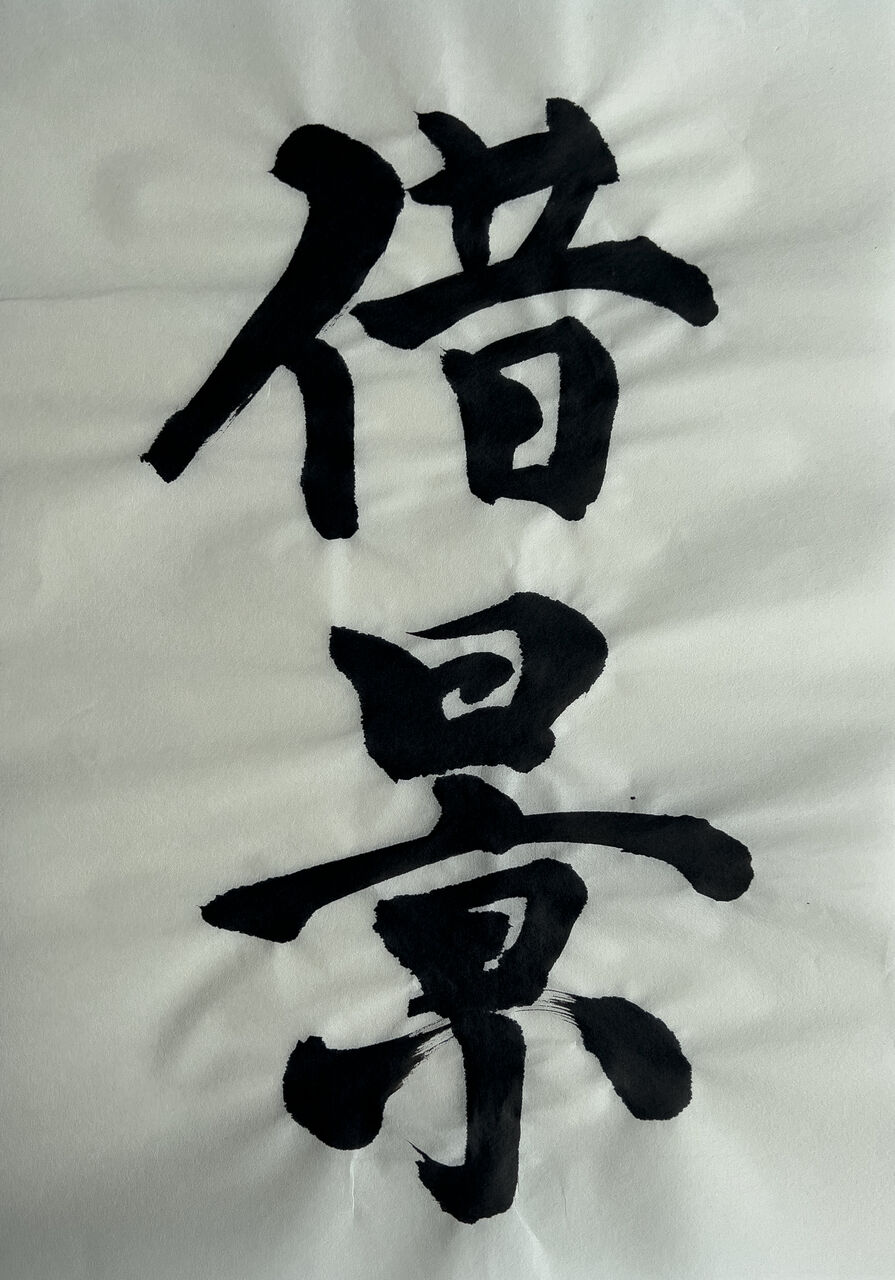

In the Japanese text Notes on Garden Making (作庭記,Sakuteiki attributed to Tachibana Toshitsuna (橘俊綱 1028–1094 CE)), borrowed scenery shakkei in Japanese, jiejing in Chinese was introduced as an approach to cultivating gardens. Borrowed scenery includes features from beyond the garden as elements in its design — mountains or rivers, clouds, rocks, and even stars. Although the garden and the surrounding landscape may be topographically separate, visually “borrowing” or “lending” each other’s attributes is an invitation to experience them as a whole. Horticultural sampling, incorporating distant aspects to create impression of something more, other, or beyond.

Borrowed Scenery by Maki Ueda

Borrowed Scenery by Maki Ueda

The origins of borrowed scenery lie in Buddhist temples, where gardens were (and still are) designed as meditative spaces, with a hint of geomancy. Early Buddhist temple gardens in Japan used shakkei as a way of teaching humility and the interconnectedness of all beings in a layered reality. Several Buddhist meditation practices (such as mettā or tonglen) start with a focus on oneself which is gradually expanded, layer by layer, to include the Earth, the whole universe, and all sentient beings. Similarly, a shakkei garden includes its human inhabitants and their gaze, drawing them from the cultivated foreground towards the focusing frame of the garden’s edge, and finally into the background — the wild, uncontrolled, borrowed scenery.

Over the centuries the spiritual connotations faded, and shakkei became a design technique used to give the garden a painterly depth and let its edges humbly diffuse in the surroundings. Borrowed scenery gardens can be seen as miniatures of a botanically-inspired culture, with plants and humans as interconnected layers of a planetary ecology. Rather than seeing them as separate entities, we shift perspective and treat the cultures of plants and humans as a part of the same picture, where they complement and enrich each other.

Guiding principles of borrowed scenery:

shotoku no sansui(生得の山水, natural mountain river). Intending to create in the likeness of nature

kōhan no shitagau(湖畔に従う, follow the lakeshore). Planning in accordance with the site topography

suchigaete (数値違えて, irregular numerical value). Designing with asymmetrical elements

fuzei (風情, feeling of wind). Capturing and presenting the spirit of the place or subtle atmosphere

According to the 1635 CE Chinese garden manual Yuanye (園冶), there are four categories of “borrowing”:

遠借 “distant borrowing”, enshaku (jp) yuanjie (zh). e.g. Mountains or lakes.

隣借 “adjacent borrowing”, rinshaku (jp) linjie (zh). Neighbouring buildings and features.

仰借 “upward borrowing”, gyōshaku (jp) yangjie (zh). Clouds, stars.

俯借 “downward borrowing”, fushaku (jp) fujie (zh). Rocks, ponds.

Example of shakkei used in a temple garden. Tenryū-ji, Kyoto, autumn 2018

Example of shakkei used in a temple garden. Tenryū-ji, Kyoto, autumn 2018

The landscape is a picture filled with leaves, where forest rain falls in the first chill of autumn; a misty time of day with traces of humidity; damp, fresh, growing, and wet on the face. There are pools of moonlit water into which you plummet, pulled upwards and downwards at once and sucked ever deeper into a place where you can just be, behind the whirlwinds and finally at peace with the daemons. Creatures faint in a lemony scent, and sometimes the taste of peppermint accompanies problems with technical parts and nearly-destroyed nature.

Somewhere else you catch glimpses of a silvery metal in straight, angular, and machinic shapes, amidst waving grass and endless fields of fairy floss, suffused in a sweet, pinkish colour and tasting of honey. Further away, perhaps, you come to the shore of a place that may be Italy, where intensely comfortable boats float in the warm twilight. Further still, and you reach a lush, nearly deserted island where ritual initiations are taking place; you want to swim in the warm waters. In the early morning you waken to the blue, orange, violet and purple pastels of another dawn, in the mild warmth of crisp, sweet sea air, smelling slightly of fish. Or maybe this landscape is nowhere else but your parent’s garden in summertime, a bright place where time no longer matters.

Somewhere else you catch glimpses of a silvery metal in straight, angular, and machinic shapes, amidst waving grass and endless fields of fairy floss, suffused in a sweet, pinkish colour and tasting of honey. Further away, perhaps, you come to the shore of a place that may be Italy, where intensely comfortable boats float in the warm twilight. Further still, and you reach a lush, nearly deserted island where ritual initiations are taking place; you want to swim in the warm waters. In the early morning you waken to the blue, orange, violet and purple pastels of another dawn, in the mild warmth of crisp, sweet sea air, smelling slightly of fish. Or maybe this landscape is nowhere else but your parent’s garden in summertime, a bright place where time no longer matters.

—Alchumilla Umiliata

❧