These Uncertain Times

Collective taming of uncertainty are effortful achievements, requiring maintenance and upkeep.

A dynamic state, on its own terms

Uncertainty is typically encountered as an unwanted problem, prompting discomfort and unease in those affected. This charged emotional response often conceals the extent to which it is a normal part of life — not an exception, but unavoidable, ineluctable; imminent in the dynamic baseline variations of the everyday. Honkasalo, “Fragilities in life and death: Engaging in uncertainty in modern society” The uncertain are not passive victims, lying inert or immobilised. With effort, they can modulate their insecurity, attending to their ‘cognitive, emotive or behavioral reactions' to uncertainty — as the passage of time, and changes in (perceived) circumstance, shape their experiences and exposure. Penrod, “Refinement of the concept of uncertainty”

In this, uncertainty is less a label or category than a relational phenomenon. Socially and culturally situated, its appearance and manifestations vary across sites and contexts. But for someone to be uncertain, there are three conditions, thresholds of possibility. First, an object of knowledge or perception. Second, (at least) one knowing actor, assigning relevance or importance to that object of knowledge. Third and finally, a plurality of different, if overlapping, knowledge relationships; a spider-web of filaments, binding the would-be knowers and their objects of knowledge. Brugnach et al., “Toward a relational concept of uncertainty: About knowing too little, knowing too differently, and accepting not to know”

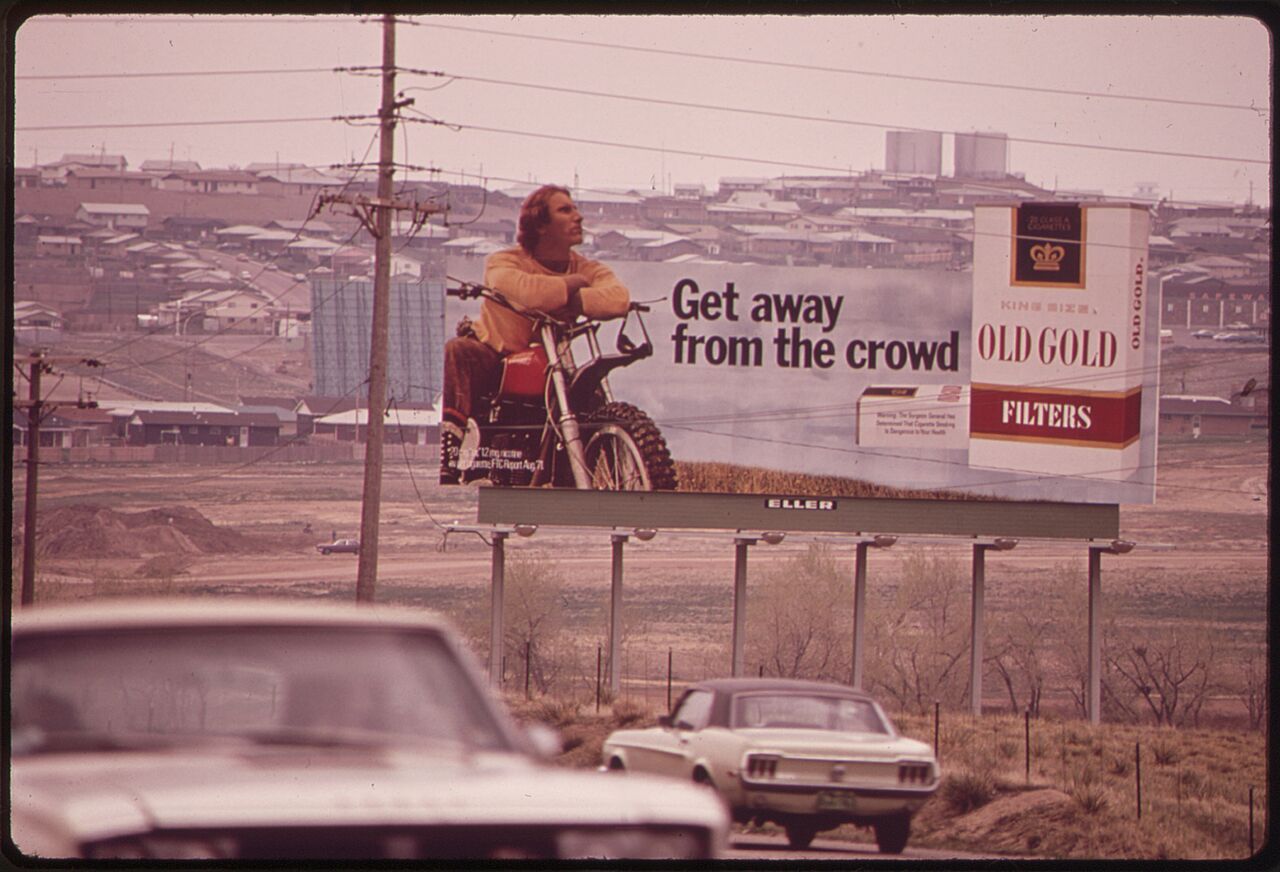

Uncertainty can be a result of incomplete knowledge, or conflicting understandings of a given situation, but it can also be caused by unpredictability, indeterminacy, and the possibility of radical novelty, through emergence and variability present in the world “out there”. It can even be a result of doubts or ignorance created by others, as in the cases of misinformation spread by the tobacco and fossil fuel industries, among others. See: Proctor and Schiebinger, Agnotology: The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance

Responding effectively and appropriately to uncertainty, getting a handle on its specificities, requires resisting a dominant tendency – particularly among powerful actors and institutions – to “treat every problem as a risk nail, to be reduced by a probabilistic hammer.” Stirling, “Keep it complex” Turning uncertainties into measurable risks requires minimising their many, often radical differences. Risk approaches can be effective in situations when the range and relative likelihood of possible outcomes are known, and can be easily quantified — as in sports betting, or futures markets. But these situations are rarer than many would assume. Future possibilities cannot always be extrapolated or evaluated from our knowledge of past events, with a reliance on aggregated data leaving probabilistic, quantified assessments noisy and vulnerable.

Decision-makers, like the rest of us, often find uncertainty threatening, as something forcing them to confront the hard limits of intentional action and situational mastery. But a preoccupation with quantifiable risk can deny decision-makers access to “dissenting interpretations”, foreclosing the possibility of surprise. Stirling, “Keep it complex” For those at ground level, waist-deep in a jostling, foaming, unruly present,far from the imagined cockpits and dashboards of top-down control, practices for engaging uncertainty are clearly required.

Flavours of Uncertainty

As a heuristic to guide action and help navigate complexity, we can approximate between three different kinds of uncertainty. Each of these only make sense as something relational, determined by details of the “relations between what is known and who is doing the knowing”. Scoones and Stirling, “Uncertainty and the Politics of Transformation”

Unpredictability. Ontological uncertainty. This flavour of uncertainty derives from the world “out there”, a consequence of the knowledge-seeker’s inability to get purchase on a dynamic, variable, radically open operating environment, populated with moving targets and emergent phenomena.

In these situations, relations of control are ineffective (the levers are too small, and there’s nowhere to stand), and additional information is of little help. The aim, instead, should be to create capacity through adaptive learning, permitting actors to respond, flexibly and effectively, to unknown, fast-changing conditions. Brugnach et al., “Toward a relational concept of uncertainty: About knowing too little, knowing too differently, and accepting not to know” In practical terms, this might involve:

- stress-testing strategies and processes against multiple possible scenarios, ahead of time For example, by using future preparedness exercises, prehearsals and preenactments.

- deliberate efforts to diversify the repertoire of possible responses

- the use of temporary adaptation strategies to buy more time (including time-limited resource deployments and short-term, stop-gap solutions)

- focusing on the consequences of the uncertainty (e.g. mopping up the mess), rather than its causes (over which you have little control)

- improvisation: including combining multiple strategies at once, to tackle different effects at different levels, at the same time

Incomplete knowledge. Epistemic uncertainty. If unpredictability is about the environment or objects of knowledge, this flavour of uncertainty links to the limited knowledge of the would-be knower.

In these cases, uncertainty could, in theory, be reduced by throwing more resources at the problem. The aim should be to improve your understanding, working to fill out your description or mental map of the situation at hand. Effective approaches might include:

- theory construction and data gathering, through, for example, fieldwork practices Having been there.

- action research cycles As in the iterative experiments of the Marine CoLAB.

- scenario construction and foresight practices (e.g. horizon-scanning, trend mapping exercises, cross-impact analysis)

- experimentation and hypothesis-testing (e.g. breaching experiments, design probes and prototypes)

- estimating ranges and confidence intervals, as a way to make the gaps and limits of knowledge more visible

- simulations (computer simulations and agent-based models, but also roleplaying, wargames, and other immersive experiences)

- seeking expert opinions (while avoiding the pressure to reach a premature “consensus” See Stirling, “Keep it complex” )

Multiple knowledge frames. Intersubjective uncertainty. Here, uncertainty derives from the relations between different knowing subjects, springing from gaps or disjunctures between their views or understandings of the objects of knowledge, or differences in their standpoints (for example, their backgrounds, political values, or forms of expertise).

Here, effective responses should target the relationships between those involved, as a proxy for mismatches in their frames, standpoints, or perspectives. This might include:

- persuasive communication, in an effort to talk dissenters round

- dialogue-based learning, to get a better handle on the differences in opinion

- integrative negotiation and collaborative decision-making: working to identify and prioritise the underlying issues, with an eye to potential “win-win” outcomes, acceptable to all involved

- controlled equivocation Viveiros de Castro, “Perspectival anthropology and the method of controlled equivocation”: not seeking to resolve the gaps or disjunctives between frames once and for all but sitting with their incompatibilities or flipping back and forth between them as useful

Uncertainty tamed

People experience uncertainty as a source of discomfort and unease because it leaves them vulnerable and precarious, threatening their material security and what they know of their place in the world. For those seeking to tame or manage uncertainty, rendering it palatable, digestible, there are things that can be done to shape their reactions and perceived circumstances. Penrod. Refinement of the Concept of Uncertainty This is not, however, to say that it can ever be eliminated, or removed from consideration; as part of the quotidian fluctuations and open-endedness of the world, these responses may be geared towards reaching an accommodation with uncertainty, a cohabitation, living-with or alongside.

Alongside internal, subjective responses, these responses encompasses practical action, finding ways to “structure, order and tame” uncertainty Adam and Groves, Future Matters: Action, Knowledge, Ethics, providing harbours from heterogeneity and social safety nets of various kinds. In cases such as these:

the future is known not through the guesswork of the mind, but through social efforts, more or less conscious, to cast "jetties" out from an established order and into the uncertainty ahead. The network of reciprocal commitments traps the future and moderates its mobility. All this tends to reduce the uncertainty.Bertrand de Jouvenel, The Art of Conjecture

Collective, projective efforts, making reciprocal, interpersonal commitments in order to render “the uncertain more certain, the insecure more secure, and the unknowable and more knowable.” Adam and Groves, Future Matters: Action, Knowledge, Ethics If uncertainty is about the relationship between the knowing subject(s) and their object of knowledge, what social or collective knowledge practices can mitigate the precarity and variabilities of everyday life?

Unpredictability and incomplete knowledge can be tamed by establishing, maintaining, reproducing relationships of trust, at different scales — through the family (kinship, blood ties), group membership, contractual agreements and obligations, and participation in society at-large (laws, norms, rules, and regulations). Trust is fragile and situated, often ambivalent, sustained through technologies of verification, epistemic practices, or, simply, “the provision of a predictable structure with familiar routines” Seshia Galvin et al., Technologies of Trust: Introduction. Trust is at once:

a problem of knowledge, a way to deal with the unknowability and uncertainty of other people; and … a problem of morality, a way to deal with the freedoms and obligations of our relations.Taylor Nelms, Trust: A Pragmatics of Social Life?

In both cases, people are the problem; and relations, techniques, and technologies of trust “become ways to navigate and manage fraught relationships in social worlds” Nelms, “Trust: A Pragmatics of Social Life?”. They embed participants’ projective, future-making practices in social frameworks of certainty, permitting the calculation of things that would otherwise be completely unpredictable. Adam and Groves, Future Matters: Action, Knowledge, Ethics.

At the scale of the household, family, kinship network, and community, the private home is, for many, a model (exemplar) harbour from heterogeneity; a space where individual experience intersects with the interests of the collective, supplying material security and a firm foundation from which to engage with the wider world. On the limits of the home as platform, the single, self-contained household and the fixed address, see FoAM’s reflections on adaptive homing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Will This Burn Down My House?

In earlier eras, those who couldn’t rely on the security of home and family could call upon an array of voluntary social institutions, from tontines A group investment providing regular payments, but in which survivors benefited from the deaths of other participants., almshouses Residential accommodation provided by a charity for the relief of poverty, infirmity, or old age., and friendly and benevolent societies Mutual associations providing pooled insurance, pensions, and savings, with membership often restricted based on religion, politics, or profession., to religious charity, and rotating savings and credit associations A group of individuals acting as an informal financial institution, with set contributions and rotating withdrawals from a common fund..

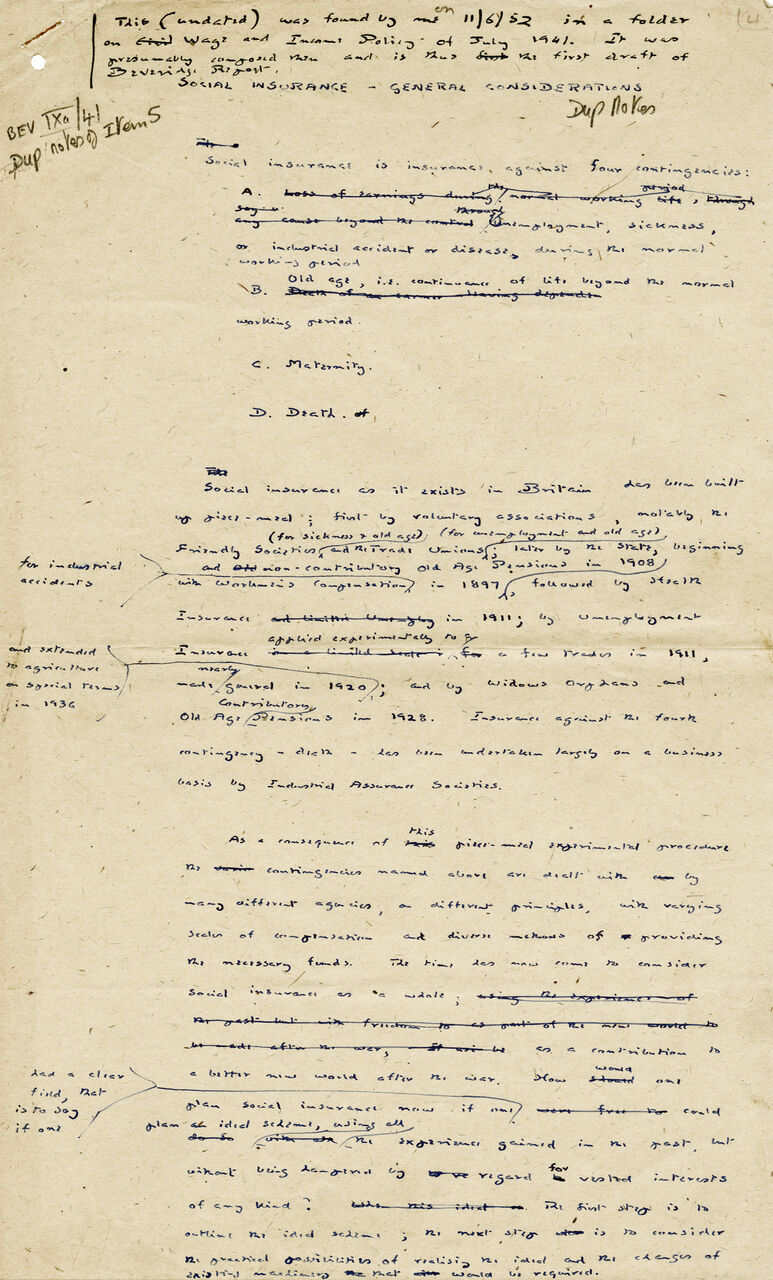

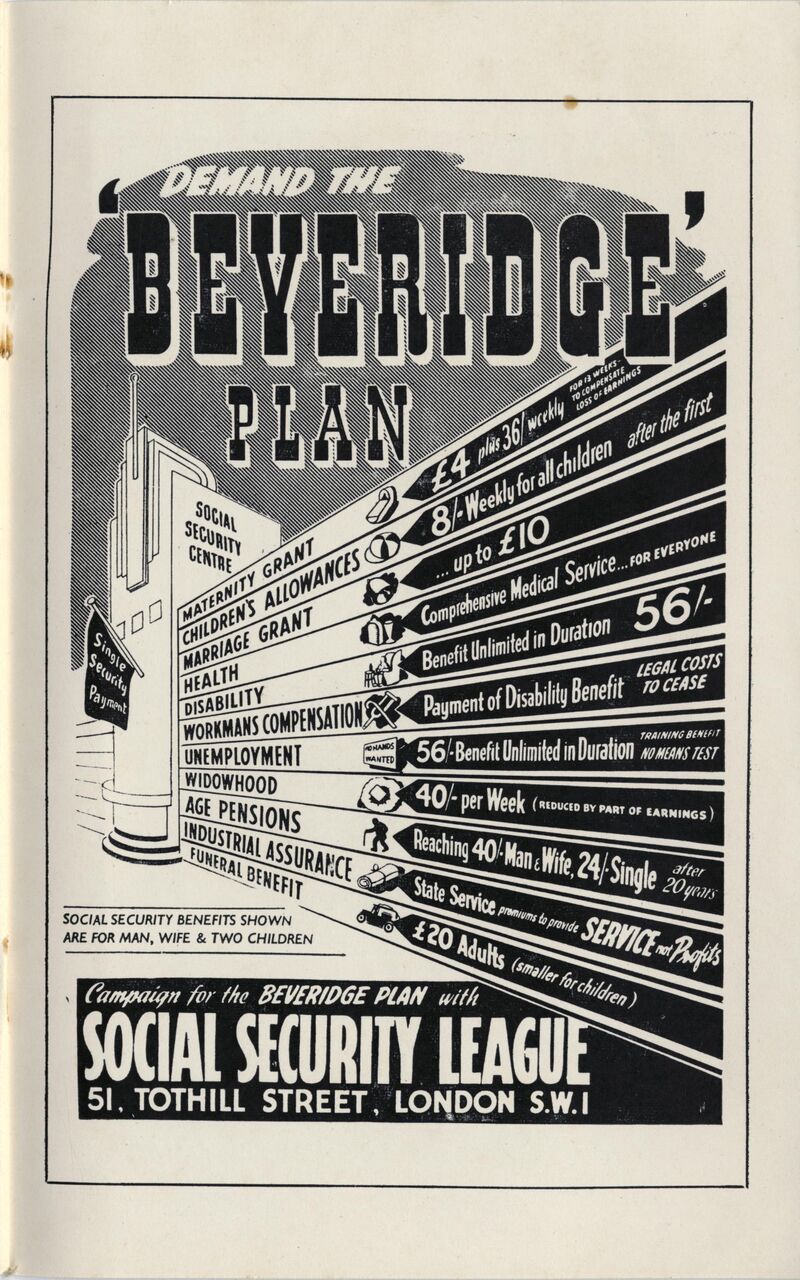

In the nineteenth-century German-speaking world, governments began to implement social security and workplace insurance programmes, alongside state pensions for the disabled and elderly, as part of projects of nation-building and economic consolidation. These new safety nets depersonalised uncertainty-taming, treated material and ontological security as a public good, providing a reliable shield from social contingencies, as funded through taxation and/or contributory payments. See Briggs, The welfare state in historical perspective Strengthened by the economic crashes of the 1890s and 1930s, such thinking sought to tame not just individually-experienced misfortune, but also the boom-and-bust cycles of the national economy. See Garland, The welfare state: A fundamental dimension of modern government In the UK, the 1942 Beveridge Report sought to “consolidate and universalise” the disparate, ad hoc seeds of the British welfare system, following the Great Depression and shared sacrifices of war. Kelly and Pearce, Beveridge at eighty: Learning the right lessons The report envisaged:

a universal system of flat rate subsistence benefits to cover unemployment, sickness industrial injury and disability, maternity, widows and orphans, funeral costs and old age … paid in return for flate rate contributions through a unified national system of social security administration... [and] contingent on the simultaneous provision of child allowances, a comprehensive health and disablement service, and the maintenance of full employment.Kelly and Pearce, Beveridge at eighty: Learning the right lessons

Though these proposals were never fully implemented, they provided the scaffold for a postwar generation of social welfare policies. Now, post-pandemic, there is a growing clamour for a new “Beveridge moment”, from those seeking a “fairer social contract on which an enduring, consensual political settlement can be built.” Kelly and Pearce, Beveridge at eighty: Learning the right lessons

Similar messages can be heard far beyond the UK: in a less certain world, amid a crisis of social and ecological reproduction, there’s a clear need for new social institutions and more responsive safety nets. Confronted with the inadequacies of state, market, and civil society voluntarism, we hear calls to rethink our models of welfare and livelihood support, Scoones and Stirling, Uncertainty and the Politics of Transformation reflecting a renewed appetite for social experimentation. This can be seen in a new raft of proposals for basic income and unconditional cash transfers, stimulus packages and helicopter money, job guarantees As in India’s Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee, which guarantees 100 days per year of paid employment in unskilled manual work; see Narayanan, The Continuing Relevance of MGNREGA , and “redundancy furlough” for longer periods of economic inactivity.

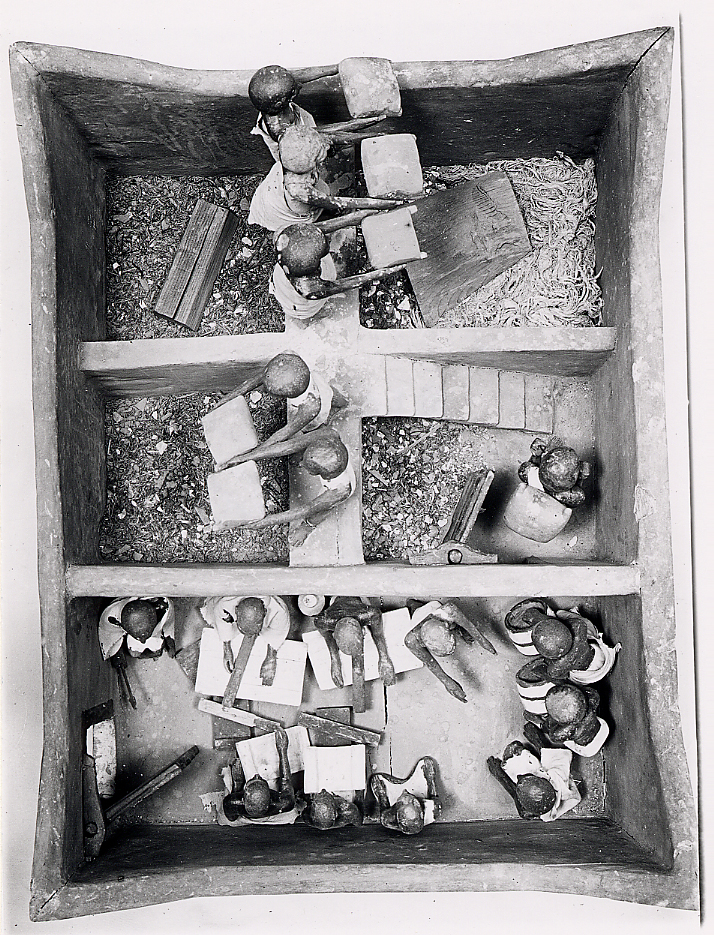

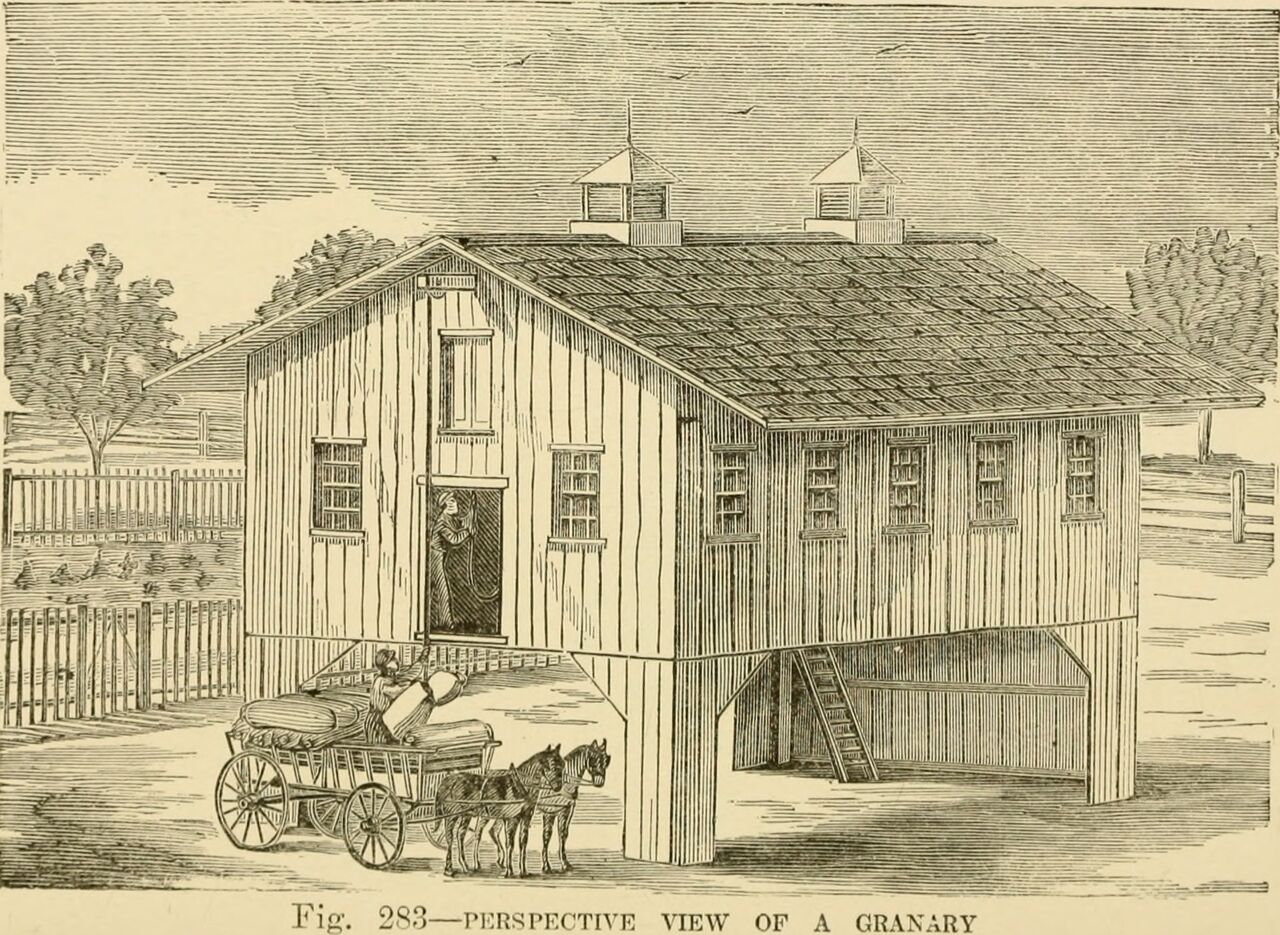

Beyond family, contract, and welfare state, it is also instructive to contemplate the material surety of the storeroom and the faucet, as infrastructural-institutional devices for regularising variable flows – and, in doing so, bringing order and reliability to the world. Storing surplus buffers the risks of environmental variability, across time and space, and the resulting shortfalls or overabundance; permitting storekeepers to act ahead of time, and take stock with an eye to future retrieval. See, for example, Van Oyen, The Socio-Economics of Roman Storage There are lessons, too, to be taken from reliability professionals; those tasked with keeping critical infrastructure — gas, water, electricity — operating, providing the relevant service, safely and continuously, even (or especially) amid turbulence. Roe, Control, manage or cope? A politics for risks, uncertainties and unknown-unknowns

Collective tamings of uncertainty are effortful achievements, requiring maintenance and upkeep. As an example of what can happen if they are permitted to falter, or fall into dormancy, we can consider anthropologist Jennifer Johnson-Hanks’s writings on 1990s–2000s Cameroon. In this setting, the reification of uncertainty amid an atmosphere of crisis undermined her interlocutors’ social and personal relationships. Mobilised as a general-purpose excuse for any and all manner of disadvantageous outcomes, appeals to “the crisis” allowed people to dodge responsibility for their actions — sapping trust, and the social pressure to engage in transparent, reliable behaviour. Johnson-Hanks, When the future decides: Uncertainty and intentional action in contemporary Cameroon Or we could consider the COVID-19 pandemic, where personal and institutional appeals to “these uncertain times” were used to claim a common context; “offering uncertainty as a kind of community.” Velocci, These Uncertain Times With this refrain, shared uncertainty legitimated a bracketing and diffusion of responsibility — much as in crisis-era Cameroon; painting cruelty and timidity in the face of incomplete knowledge as a reasonable response to the churning variability of a (suddenly hostile) external world.

Across the manifold fringy, splintered, peri-urban tendrils of this, a world of “multiple shocks, surprises and contingencies”, our remaining illusions of control must be supplanted by better practices of “managing and coping-ahead” in the face of “real-time unknown unknowns”. Roe, Control, manage or cope? A politics for risks, uncertainties and unknown-unknowns See: Part of the network, in the moment, aware of the times. By considering uncertainty as a dynamic, relational phenomenon, part of daily life, mediated or mitigated through projective social practices and everyday hedgings, See: Everyday Hedging. it is, perhaps, easier to glimpse what this might look like in practice; extrapolating from how a wide range people in diverse settings and situations are already coping-ahead — working (more-or-less successfully) to sustain a semblance of reliability, continuity, and forward momentum under turbulent, unpredictable conditions.

🝓

Further reading & references