Taking Risks or Making Risks?

Complexity, uncertainty and possible futures in the context of technological innovation and entrepreneurship.

Excerpts and images gleaned from FoAM’s lecture performance at the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in March 2019.

How to embrace complexity and uncertainty, in order to act in meaningful ways, whatever the future may bring?

We suggest to:

- Challenge your assumptions

- Improve your collaborative skills

- Contextualise your work

- Experiment with futureproofing

- Embrace serendipity

- Design for failure

- Prototype and iterate

- Build antifragile systems

- Cultivate interconnected approaches

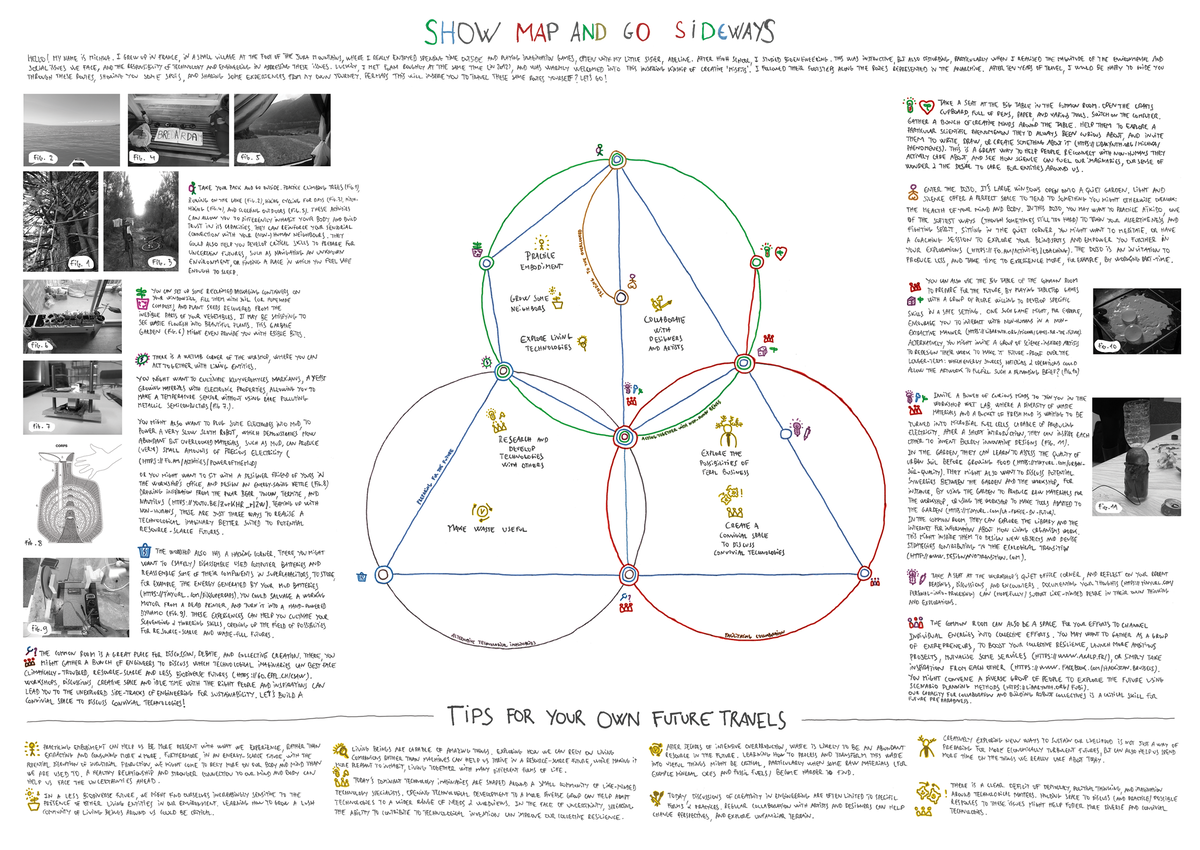

>> Show Map & Go Sideways by Michka Melo, an example of how these principles can be put to work in practice

>> Show Map & Go Sideways by Michka Melo, an example of how these principles can be put to work in practice

Challenge your assumptions.

To give your ideas a solid foundation for meaningful change, translate your assumptions into hypotheses and test their validity in real life and with other people. To understand what might be going on in a system, observe before interacting. Take your time to understand and take different perspectives before interfering. Correlation is not causation. Causation is not mechanism.

Improve your collaborative skills.

Acknowledge that creativity comes in many guises and should be valued as a shared resource. Collaboration will improve your chances of dealing with complex problems in meaningful ways. One person’s weakness is likely someone else’s strength. When combined, they can complement and support each other. Work with people you are able to disagree with.

Contextualise your work.

Understanding the context will allow you to innovate from different perspectives and for multiple benefits. When you take externalities into account you will be able to surface less apparent risks and unexpected opportunities.

Experiment with futureproofing.

Question where your ideas about the future come from and who they are for. Design with multiple futures in mind. Improve your capacity to deal with uncertainty of the future by building tighter feedback loops between vision and adaptation.

Embrace serendipity.

Some of the most important discoveries in human history happened by chance. Acknowledge that seemingly aimless exploration can lead to surprisingly innovative results. Leave room for the unexpected, the unplanned and the inconsequential.

Prototype and iterate.

To make your work more adaptive to changing conditions start with prototyping — think about what would be the simplest way to test your idea with minimal resources and in the shortest time possible. To reduce risk, iteratively scale up or change scope of experiments. Think about dosages.

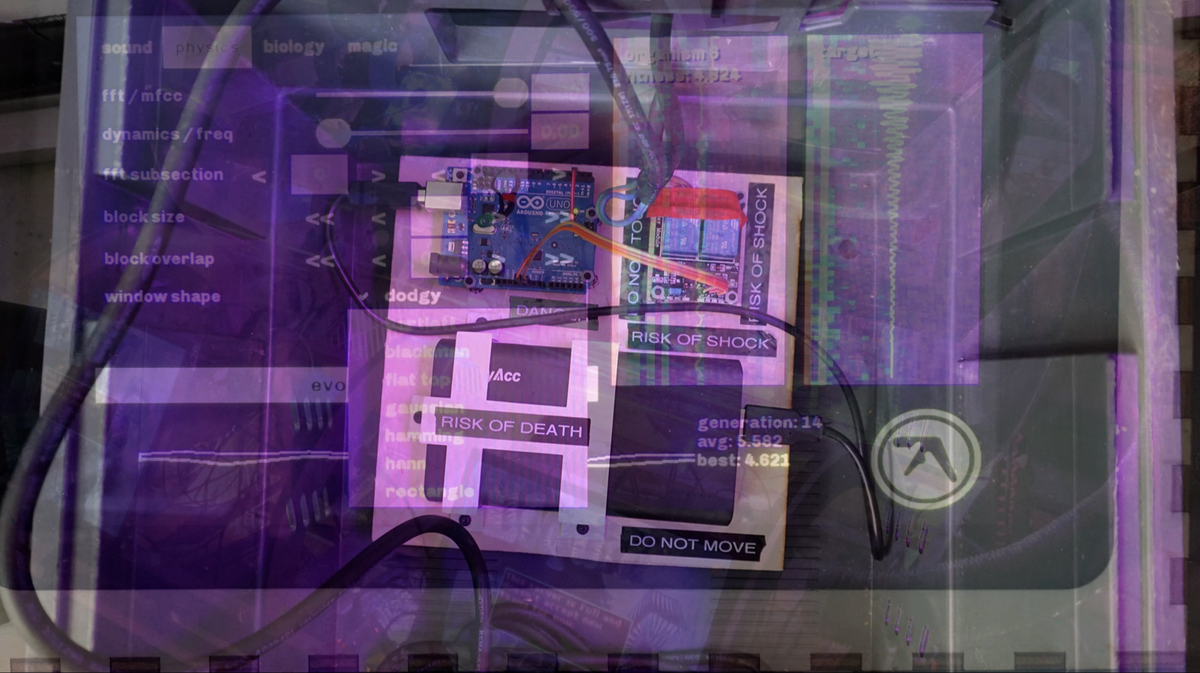

Design for failure.

Being aware of the problems your solutions could cause can help reduce unintended consequences. To minimise damage caused by your ideas being corrupted and abused, design with worst-case scenarios in mind. Failure is important, but only if you learn from mistakes.

Build antifragile systems.

Designing systems that become better through adversity will improve their capacity to thrive in uncertain conditions. When building or engaging with complex systems, apply the tactics of decentralisation, redundancy and overcompensation to avoid catastrophic failures.

Cultivate interconnected approaches.

To reap the intangible long term benefits for everyone involved, engaging with complex problems requires a change of mindset from reductionist to relational. To assure a wider take-up of systemic outcomes, open your sources and share your findings with a wide community of stakeholders.

What can go wrong?

Innovation focuses on creating radical change in existing fields. It aspires to shape the future using the tools of the present. While innovation is one of the ways to “invent the future”, it is also shaped by existing circumstances and changes in the present. With increasing environmental, economic, and political uncertainty, it should be apparent that technological innovation alone cannot “fix” things. Simple “solutions” usually create unintended consequences. Creating anything in such turbulent times brings with it a sense of agency, but also responsibility. When we intervene in complex systems, our future-shaping actions are hard (or perhaps impossible) to predict.

Innovation, like any other human endeavour, is a situated practice. It is grounded in the experience of the innovators themselves and the context in which you are working. In your backgrounds, in your personalities, your interactions with other people and situations. Even the most straightforward technological innovation will have your own assumptions about the world built into it.

Incorporating your assumptions into the process of innovation doesn’t have to be a problem, as long as you are aware that your assumptions are not generalisable facts, and, as long as you are willing to seriously take other perspectives into account. One such perspective is that innovation has become fetishised for its own sake, with little regard for the underlying ethics, politics and worldviews that enable it.

Innovators can perpetuate unsustainable lifestyles and social injustices, often without even being aware of it. For example, the household innovations of the 1950s, such a the vacuum cleaner or the dishwasher, certainly improved the quality of life for the housewife, without questioning a social order where women are expected to be housewives. The automated dishwasher was invented in 1872 by Josephine Cochran, in her search for alternative ways of washing her heirloom china after some precious dishes were chipped by reckless servants. However, the dishwasher only became a household fixture with the ready availability of water heaters in the 1950s. Yet neither Josephine nor the engineers of the 1950s seriously questioned the availability of servants and housewives.

Test your innovation by exploring all the ways in which things can go wrong.

Don’t simply focus on what would be ideal or critique the status quo. Genuinely examine how what you’re seeking could also be corrupted and abused. I believe, more than anything, that deep empathy and self-reflection is critical for us to build a healthier future.Danah Boyd, The Radicalization of Utopian Dreams

In a world of context-aware technologies, we could benefit from more context-aware innovation. If innovation is about introducing new technologies, new methods, and new approaches to old questions, it should also ask new questions to solve current problems from new perspectives.

If you want innovation to matter you must consider not only its direct impact, but also its reverberating implications and unintended consequences in the world. Design for how your innovation can go wrong. What does User Centred Design look like when “The User” is a genocidal dictator or a psychopathic CEO with the resources of a small nation? If such possibilities are not taken into account during planning, you may be facing the consequences of death, destruction, or the minor banalities of evil during production. On the other hand, if an innovation can help prevent its own misuse, it’s more likely to remain a force for good.

Innovation aims to shape the future using the tools of the present. In the process the tools themselves are inevitably transformed. A tool designed to shape a particular future is in turn influenced by the visions of that future. This can create positive feedback loops, but it can also be a dangerous path. It is essential to question your “default future”, [O]ur unquestioned image or assumption of the future, whether for our world, organization or ourselves. Challenging this default future, we are then able to imagine and articulate alternative and desired futures.

José Ramos. Linking Foresight and Action: Toward a Futures Action Research the presumption that the future can only go a certain way, that it will be mostly like the present, just a little bit better, faster and brighter. The default future is often assumed without critically examining or testing it in practice.

Ask yourself: Where does my image of the future come from? Is it an image I’ve created, borrowed, or been given? Is this a desirable future? It is mine or is it someone else’s future? If you attempt to innovate without challenging your own assumptions about the future, your work will likely perpetuate the same problems you may be trying to solve.

Sometimes the most innovative thing you can do is nothing at all. Other times, you might create exactly what you want, developing the most innovative technology imaginable, only to realise that it’s completely useless until the worldview and the society around it changes. Sometimes you can forget that innovation isn’t an end in itself. It’s a process, a means to an end.

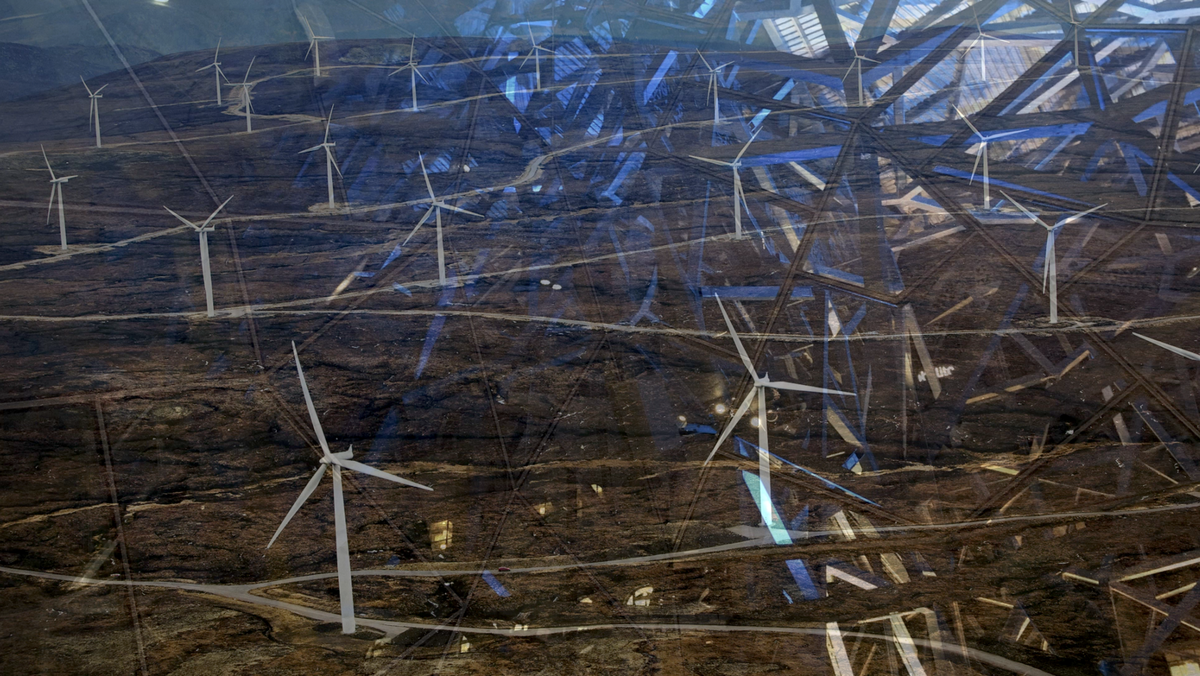

When working with complex systems you have to be careful not to become overconfident. You can’t be sure that any of your innovations will reduce the effects of climate change. You can’t even be certain about how to evaluate your proposed solutions. But you can work with specific questions and experiment with provisional answers. You can contribute to changing the conditions to make future responses possible.

You can learn from sympoietic systems, such as cultures or edge habitats. ...collectively-producing systems that do not have self-defined spatial or temporal boundaries. Information and control are distributed among components. The systems are evolutionary and have the potential for surprising change. —Beth Dempster. Sympoietic and autopoietic systems: A new distinction for self-organizing systems. These systems evolve through connections and feedback. They adapt when new information becomes available and exist in dynamic balance. Designing in such decentralised systems works best when applying simple rules, incorporating redundancy and multiplicity, working with randomness as an inherent characteristic and using noisy heuristics. It requires engagement, communication, and collaboration. See also: Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble.

Where are you going?

Sometimes innovation is about going forward. Other times it’s about going sideways, going backwards, or just staying in place and tinkering in the present. In some cases disruptive innovation is necessary to break with the status quo. Most of the time you’d better take history into account to avoid unnecessary damage. Sometimes it’s good to throw out the old, other times it’s better to repair, reclaim, and repurpose. Sometimes knowledge is power; other times too much prior knowledge can get in the way of finding viable alternatives.

Challenging your default future—the image of the future you take for granted—can be unsettling, but can also lead to surprising opportunities. You don’t need to invent fantastic futures either; it’s enough to keep an open mind in the present. William Gibson’s famous maxim “the future is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed” encourages us to look more closely at the present and question the means of distribution. The fluid nature of futures. If you don’t take one path for granted, other possible paths can open up. Innovation can be found in the most unexpected places.

Some Notes on Transdisciplinarity

Further reading & references🝓