Recovering Experts

Co-founder of Then Try This discusses working across fields and sectors, collectively creating knowledge; the AccessLab project distributes research skills beyond academia, bringing together people who would not have otherwise crossed paths.

Another project, The Evidence Support Initiative, engages research with policy, local politics, and where decisions that actually affect people get made. Dave addresses who has access to what research and how that affects decision-making at different governmental levels.

Read the full interview on FoAM’s blog.

MW: I was reading something about diversity of sectors in one of your texts and I was wondering if you could speak to that theme, and how important that is for Then Try This’ work and commitments.

DG: That’s a line that we can draw straight from the FoAM network’s approach to things. Amber [Griffiths] and me, similar to most of the people in FoAM, are both recovering experts. We’d reached that point in our careers where, you could just map out, you just knew your own rails, right, you know where you’re going to end up. Amber left her academic career literally on the day that she got tenure. So she did all of the hard work to get there and then that day it was like, “Nope. Jump off.”

MW: I feel like I personally and probably many more people could do with examples of celebrating, not just generality, but really, really deep curiosity, but in multiple directions. Taking Risks or Making Risks

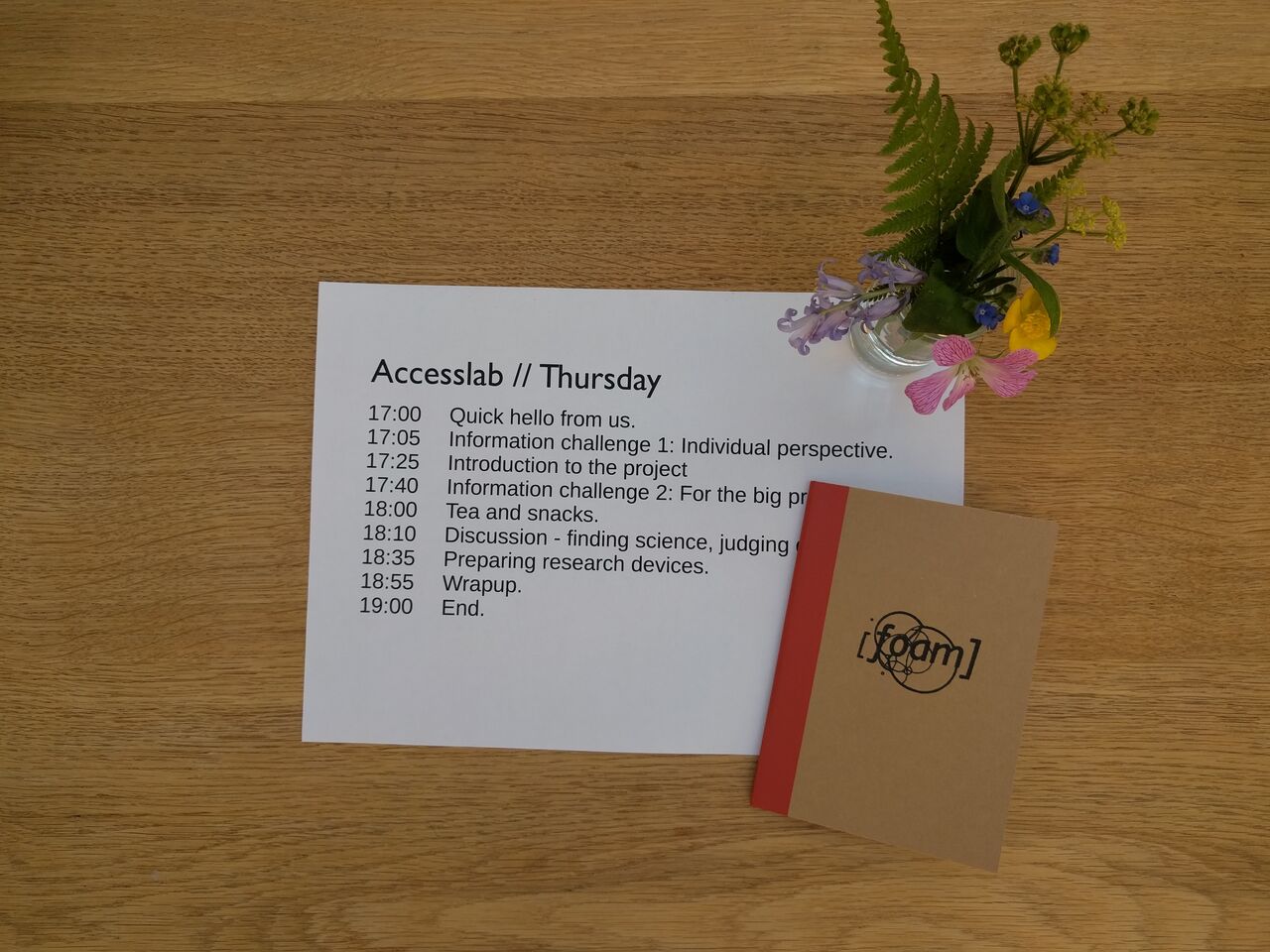

AccessLab

MW: I have a question about the value and importance of citizen based-projects and game-based projects. I’m wondering what these approaches can do that other approaches can not.

DG: Amber’s got a really good diagram of citizen science and it stretches from, on one extreme it’s crowd-sourcing — get thousands of people trying to solve this problem. That’s what a lot of scientists think citizen science is: let’s get “the public” to solve our problems. And that’s not really what we’re interested in. And then it goes all the way to the sort of gold standard citizen science approach, where people are actually coming up with the questions that they want answered. A citizen science scale:

1. Attend educational stuff (exhibitions, talks)

2. Contribute processing power (BOINC)

3. Contribute data (crowd-sourcing, bird surveys, Zooniverse)

4. Problem solving (for example Fold It)

5. Question raising (Dutch and Belgian science shops “wetenschapswinkels”)

6. Drive own research (the DIY Bio movement, for example)

7. Co-create new scientific culture (for example Biohackspaces)

And we’ve been doing this where we pair up researchers and local people from different professions and they’ll come with questions that they want help learning to answer. And that can actually lead to whole new sorts of research projects. But it also leads to changes in the law and things like that, so suddenly you’re making all of this kind of stuff possible.

That’s the AccessLab project. Griffiths et al. AccessLab: Workshops to Broaden Access to Scientific Research. And the thing about that is where we have somebody that wants a question answered, we’ll pair them with a researcher that hasn’t got a background in that thing, because then they have to learn with the person. Because they don’t switch on teaching mode, because that’s the worst, if you’re working with an academic, and they go, “Ah! I’m teaching you!” *laughs* “Sit there and absorb my knowledge!” And if it’s something that they’ve not done before, actually the important thing is, you know, “Where can I look for papers”, and, “Can I trust this author? What else have they published? Where have they published? Who are they funded by?” and all these questions that 99% of the population don’t have so much experience asking. So that’s our gold standard citizen science project where it’s actually the “citizens” driving the science rather than the other way around.

So that’s really the knowledge that the researchers have that they don’t realize they have. And they don’t realize how important that is. We’ll be working with people who can then present all of the papers that they’ve found together as evidence for something that they need changed, that’s going into law, courts… for one project we had evidence given to lawmakers locally for some changes as well.

One of the key skills developed in AccessLab is assessing research publications.

Here are some questions to judge the reliability of published research:

Can you find the original research? Is there a link in the media article, or can you find it by searching for the named researcher in the article?

Who did the work? Can you find the researcher anywhere online? Do they work for a university or similar non-profit organisation, or do they have either no apparent affiliation or an affiliation that might indicate a strong bias?

Who funded the work? Usually this is stated at the start or the end of the research article. If the funder isn’t stated, or if there are clear conflicts of interest (for example, the research is about lung cancer and is funded by a tobacco company), then there is good reason to be cautious.

How was the work done? This is tricky, but there are simple things to look out for. Be cautious of claims made about humans based on research done on other animals like mice, be cautious of research involving very small sample sizes, and be cautious of review papers that don’t state that they are systematic reviews.

Did the research actually do what the media article says it did? Sometimes there are clear disparities, for example, a media article that talks about social media causing cancer while the research article did not actually involve any research on social media causing cancer.

What have others published previously and since? Can you find other research papers that show the same thing, or do more recent papers debunk the work?

Can you access the data? This is the gold standard. There should be a link to the raw data somewhere in the research paper. If the data has been made freely available, then it is less likely that the researchers have anything to hide as it is open to scrutiny.

On a Local Level You Can Have a Huge Effect Quite Quickly

MW: While knowing that evidence is always subjective, I was wondering if you could talk a little about that for, say, somebody with research skills who wanted to offer that to policy land.

DG: A few years ago Amber was on our local parish council, which is the people who make decisions for the town we live in and the one next to it. So very, very small-level. Which I always found quite funny because she also worked at European Parliament and Westminster as well, and it’s kind of similar. It was discovering that while, obviously, the sort of national-level politics have access to research, how much they listen and how that exactly works is a whole ’nother story. But local policymakers don’t have any support for this at all. So they’re just bumbling around like the rest of us, trying to work out… they don’t really know what they should be reading, or what’s out there or anything. And so one of the things that we’ve been doing in the AccessLab model is actually asking people where they find their information. So one of the really nice exercises we do — and we do this with the policymakers but also the researchers — is saying, “You’ve been diagnosed with leprosy. What’s your next step? Where are you going to look for information?” And what’s really funny about this is that researchers who aren’t medical researchers, they look in exactly the same places for information pretty much as policymakers or whatever. It’s kind of showing that none of us really know where to find information.

MW: I didn’t know that local council members wouldn’t have access to data the way that national ones would.

DG: Yeah, and the shocking thing in the UK is that even doctors don’t always have access to paywalled journals. So as soon as something’s behind a paywall, it’s completely useless for anybody that isn’t in a university. Which is ridiculous, because a lot of the really important stuff is paywalled. A lot of what we do in that project comes down to teaching researchers how to talk to people and how to actually be helpful. And it is a lot of that, like, not getting them to teach, and understanding that their years and years of understanding how knowledge is judged and how to find effective information is a really important skill, and to elevate that rather than how much they know about that specific bacteria that nobody’s ever heard of. So a lot of it is in just re-framing it for the researchers so that they see things a slightly different way. We’re trying to get the project that will do this on a wider scale off the ground, to roll this out in a few more places. Because we’ve had really good success doing it in small trials and getting actually cross-party support; across the political spectrum we’ve had people involved in the project, which is also, I think, really key.

MW: Does this make you optimistic about future politics in the UK?

DG: That’s a complex one. I think one of the things that I do is, I hadn’t really realized, is, to some extent, how I think the tiny-level, local — and I think it’s probably the same in the States, in a lot of countries — politics is actually probably where most of the decisions that affect most people are made. So the power is actually slightly higher than you’d think. And it’s just stuff like, how’s the rubbish collected, who gets to build where, all those kinds of decisions are actually quite outsized compared with a lot of the things that the national-level politics is about. And a lot of the problems to deal with on a national level are never going to be solved. Whereas the problems on a local level you can actually have quite a huge effect quite quickly. So I wouldn’t say optimistic, but there might be more room for improvement than we think. *laughs*

🝓