Notes on Transdisciplinarity

Being transformed while working through and across disciplines.

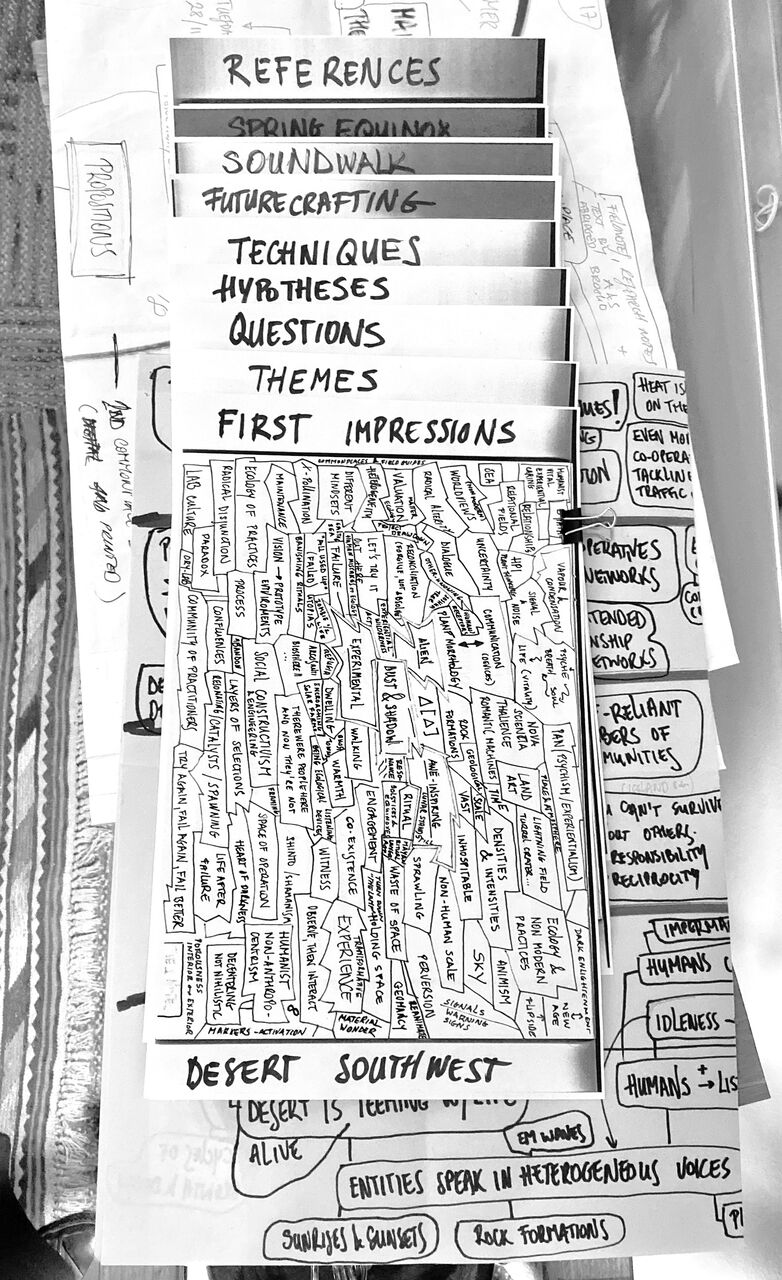

Adapted from FoAM’s notes written in preparation for the panel discussion “Desert Humanities: Creating Interdisciplinary Collaboration” at the Arizona State University, on the 23rd September 2019.

Why do transdisciplinary projects matter?

What do they do that other projects do not?

Transdisciplinary projects have the potential to make what we do more widely relevant, and change how we do things to be more inclusive of different points of view. The most pressing concerns of the 21st century are too complex to engage with from a single point of view (like climate change or systemic injustice).

Transdisciplinary projects can answer why these concerns are important to a broader and more diverse group of people. Being part of such projects requires everyone involved to get to grips with the subject matter from multiple perspectives. When confronted with different points of view, the collaborators can better notice (and break through) individual filter bubbles. This experience can make those involved more humble, curious, and open-minded (though that's not always the case). Working with people from different disciplines and cultures can challenge each participant’s blind spots and assumptions, helping the team get a more nuanced and clear understanding of the issues at hand.

When it comes to the how to engage with these concerns, the transdisciplinary toolbox becomes a treasure chest of techniques and methods that can be applied, complemented, and combined. The process becomes richer and more playful, as we learn, adapt, and stretch each other’s habitual ways of doing things. When they work well, what comes out of transdisciplinary projects tends to have multiple benefits. They’re less likely to produce simplistic single solutions (that often cause problems elsewhere) and can have wider reaching, more holistic outcomes, where the divergent parts work together to create an interconnected whole — although they can also result in unwieldy, impenetrable systems.

Just being labelled as “transdisciplinary” is not enough. Transdisciplinarity matters when it transforms the characters, their interactions, and the collaborative processes involved. When it breaks silos between previously segregated knowledges and encourages a respectful co-existence, and (if appropriate) a mutually beneficial cross-pollination between them.

Why? Because our lives — even our continued survival, as humans on Earth — might depend on it.

What to keep in mind when embarking on a transdisciplinary project?

What are some of the risks, problems, benefits, and rewards in transdisciplinary projects?

Risks, problems, benefits, and rewards tend to be context-specific — most of them can't be generalised for all transdisciplinary collaborations. What follows is a few that can.

Rewards

- Expect to be surprised (+/-)

- Often unexpected and more widely relevant outcomes, towards more systemic change

- Continuous learning, opening of horizons…

- Once agreements are reached, more work can be done in a shorter amount of time with people from different disciplines

- A remedy for overconfidence (constant experiencing of “I know that I don't know”)

- Finding relevance of one’s work outside of the narrow domain of a discipline; methods from one field applied in many others

Risks

- Expect to be surprised (+/-)

- Things will likely take longer and require more resources than you expect

- It is difficult to specify concrete outcomes beforehand

- People can be reluctant to leave the comfort zones of their own discipline. No real collaboration, exchange, and respect between different experts involved. The results remain within disciplinary boundaries and have no real impact outside of their narrow problem domains

- A mismatch of priorities between research and production, theory and practice

- Reliance on experts without sufficient understanding of the problem domain

Some things to keep in mind...

About yourself

- Embrace your beginner’s mind, be curious

- Be aware of unconscious biases

- Get out of your comfort zone

- Don't take yourself too seriously, just seriously enough. It’s important to laugh with each other

- Despite what you might think, you are not superhuman. Sometimes it is better to share your burden with others, and sometimes the best thing you can do is to give up. Some collaborations are not meant to be

About your collaborators

- It is just as important who you work with as what you work on

- Your collaborators are sentient beings sharing a human experience; field affiliations and job titles are secondary

- Find resonances between collaborators. From a place of resonance it is easier to probe the unavoidable differences

- Cultivate an ecology of practices Isabelle Stengers in “Ecology of practices and technology of belonging” grounded in “experimental togetherness”

- Build in sufficient diversity, but also enough overlaps and redundancies

- Foster “unholy alliances” Luminous Green

- Socialising and relationship-building is an inextricable part of collaboration

- Collaborations can have expiration dates, or can grow to become whole communities or cultures

About transdisciplinary collaboration

- Collaborate on something you all care about, aware that everyone has their different motivations, priorities, et cetera

- Approach your area of interest from different perspectives for multiple benefits

- Work on the edges between disciplines. True inter/transdisciplinary collaboration doesn’t just use skills from one field to improve another (artists making slides look good, technologists acting as technicians) but rather offers chances for each to expand their skills

- Question the vocabulary; the same words can mean very different things for different people.

- Acknowledge and apply multiple ways of knowing (including tacit, embodied, subtractive, tinkering…)

- Share your sources, processes, and results

- Apply adaptive evaluation cycles to increase resilience and heed early warning signals

- In theory there is no difference between theory and practice, while in practice there is? Benjamin Brewster, Theory and Practice, 1882

About the (transdisciplinary) collaborative process

- Hold space for unexpected things to emerge

- Encourage peer learning and co-creation

- Transform every statement into a hypothesis

- Focus on options

- Don’t get consumed by facts and data

- Conduct lots of iterative experiments, scale up or change with every iteration to reduce risk

- Do not take your collaborators for granted. Celebrate successes, failures, and everything in between

🝓

Further reading & references