Dimensions of Experience

A (very) preliminary theory of futuring by Paul Graham Raven, a writer of poetry and fictions, a (gratefully) lapsed consulting critical futurist and narrative designer, and a literary critic and occasional journalist.

In discussing the practice whose name he coined, Stuart Candy describes experiential futures (XF I will use the initials XF throughout this essay to abbreviate “experiential futures” as both a) a particular mode of futuring and b) the futures produced through the use of that mode.) as “a tangible ‘what if’, more textural than textual”, which gets at the product, and “a way of thinking out loud, materially or performatively, or both”, which gets at the process. See: Experiential Futures: Brief Outline Candy is addressing designers, but there are useful concepts here for those who come to futuring from other backgrounds, and I want to start by looking at two such ideas.

XF is sometimes positioned in opposition to narrative-based methods, which tend to be more textual than textural. There are, for instance, various species of foresight and trend reports—at which, I think, Candy is implicitly aiming his opposition—and then there is science fiction.

Julian Bleecker has observed that design fiction is not science fiction. A argument frequently made by Bleecker, and discussed at some length in Where is Design Fiction Nonetheless, the two modes share an undeniable commonality, which I would describe as their capacity for the exploration of futurity. I use futurity to identify the potential for things to be different in times yet to come. This is distinct from futures, which reflect particular possibilities (however probable) within that broader potential. Both are distinct from and opposed to “The Future”, a sales pitch masquerading as prophecy, the mark of zealots and charlatans. Science fiction’s textual toolkit—including not just prose fiction but film scripts, audio drama, even poetry—can also be deployed to activate agency. My colleagues and I The colleagues to whom I refer are members or allies of the Climaginaries research network call this work narrative prototyping, to indicate its sharing in the ends of design fiction.

Where experientialists go to design and the arts for their techniques, we narrativists have instead turned to literature, to the textual. So this is a difference of methods, of media — but is that difference fundamental? Are the two approaches incommensurable, destined to evolve apart?

I believe not. I think of them as two ways of looking at one thing: the work of depicting future(s). And there are many more than just these two! But what distinguishes these approaches is the ethical ends of their depictive means — opening up a futurity which has long been closed and professionalised. But how might we think through these differences and similarities, and what might we gain from doing so?

Toward a Unified Theory of Futuring

All modes of futuring produce things that can be understood as narratives — not just experiential and narrative forms, but also foresight reports and projected-profit graphs and architectural maquettes and consumer electronics advertisements, all of which, knowingly or not, manifest futurity.

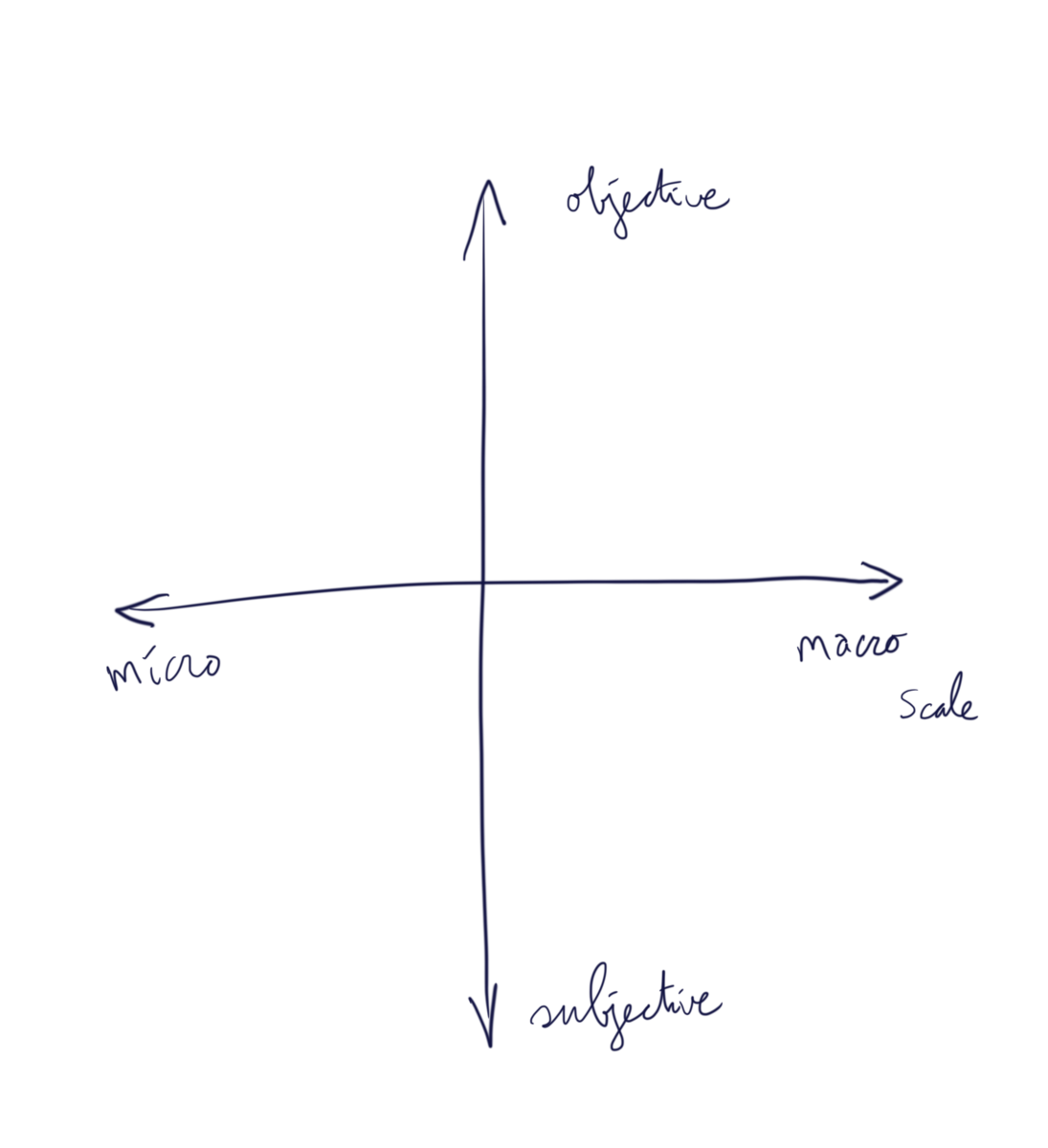

My main tool for presenting this argument will be the 2x2 matrix which has, for reasons fair and foul alike, become a cliché of futures work. To turn an overused and underexamined method back upon the field as a tool of methodology seems apropos, particularly when it comes to its more liminal and vital practices — but it also provides a simple, accessible way of thinking about the distinct dimensions of a thing. So: when it comes to futuring, we can consider two dimensions along which any given work can be placed. Those two dimensions are scale (X-axis) and perspective (Y-axis).

Scale x Perspective

Scale x Perspective

Scale is the easier axis to grasp. Futuring at the macro scale deals in abstraction and generalisation, trends, the “big picture”; by contrast, futuring at the micro scale uses specificity, and is more concerned with individual practices and “the local”.

Taken to its ultimate expression, macro is futuring at the scale of a world, of a planet: a good example might be the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s reports. The micro, conversely, is best exemplified by ethnographic approaches: depictions of things and activities at the human scale. But scale is a spectrum rather than a binary, so a work of futuring dealing with a nation-state is more micro than a global report, but more macro than something that handles a city or sub-national region.

Perspective is a little trickier. As a writer and narratologist, I prefer to call it point-of-view, or even focalisation... but perspective requires less in the way of theoretical baggage. One extreme of perspective is objective, which we might also call disembodied: think here of the camera-eye of cinema or the voice of reportage journalism, which purport to portray events “as they really happened”. Though this claim is often made sincerely, the scare quotes emphasise that this objectivity is false. Readers may recognise this perspective as what Haraway named the “god trick” of technoscientific discourse, or as the third-person objective (or detached Ursula K. Le Guin, Steering the craft: A twenty-first century guide to sailing the sea of story. Written for beginning writers, this is a great introduction for anyone with an interest in how story works, and how to make it work.) point-of-view.

The eyes have been used to signify a perverse capacity—honed to perfection in the history of science tied to militarism, capitalism, colonialism, and male supremacy—to distance the knowing subject from everybody and everything in the interests of unfettered power. The instruments of visualization in multinationalist, postmodernist culture have compounded these meanings of disembodiment.

The visualizing technologies are without apparent limit. The eye of any ordinary primate like us can be endlessly enhanced by sonography systems, magnetic resonance imaging, artificial intelligence-linked graphic manipulation systems, scanning electron microscopes, computed tomography scanners, color-enhancement techniques, satellite surveillance systems, home and office video display terminals, cameras for every purpose from filming the mucous membrane lining the gut cavity of a marine worm living in the vent gases on a fault between continental plates to mapping a planetary hemisphere else where in the solar system.

Vision in this technological feast becomes unregulated gluttony; all seems not just mythically about the god trick of seeing everything from nowhere, but to have put the myth into ordinary practice. And like the god trick, this eye fucks the world to make techno-monsters.

Donna Haraway

This perspective implies the absence of a narrator mediating between the audience and the world depicted. A self-effacement of narratorial influence, such objectivity, in its most common sense, is an impossibility that conceals (or attempts to) its author(s)’s agenda.

The other extreme is the subjective or embodied perspective: think of a story told in the first person (e.g. “And I awoke and found me here on the cold hill’s side…”), or limited third person. The limited third person is perhaps the dominant mode in contemporary prose fiction. Rather than the first person’s “I”, the focal character is “she” or “he” or “they”, but the story is still told from their necessarily limited perspective on the fictional world and its events. There are many more technical differences, which Le Guin (see reference above) explains more concisely than I. This foregrounds the subject through which the depiction is narrated, allowing access to their senses, experience, thoughts, and feelings—their interiority—and thus to a sense of context and history; to refer again to Haraway, this is more like the “situated knowledges” she advocated as a corrective to the god trick. Given that any work of futuring is necessarily fictional—speculation only becomes prediction in hindsight (the claims of pundits notwithstanding)—the honesty of the subjective perspective in this context is just as unreal as the “objective”. I, like Haraway, may have axes to grind (pun not entirely unintended) with the “objective” perspective deployed in futures work, but it is not inherently bad or wrong; and, indeed, it can do work that the subjective cannot (and vice versa).

From Theory To Affordances

With this 2x2 map, we can roughly locate any given work of futuring (or part thereof) within its dimensions; enabling us to compare works and consider which methods or media work to achieve particular effects. Note that pure methods are rare in futuring: whether by plan or instinctively, those attempting to depict a future will reach for a range of rhetorical affordances.

Some examples may be illustrative. We might consider the science fiction story as a single-media mode of futuring, but our map shows that, while a novel is all text, it can incorporate many sub-modes. In science fiction criticism, the term “infodump” is used to label exposition enabling lots of worldbuilding within a limited word-count: multiple paragraphs, even pages, given over to direct description of a fictional future. Writers from the genre’s so-called golden age As the old joke would have it, “the golden age of science fiction is twelve”. Less flippantly, the golden age arguably falls somewhere between the start of the 1930s and the start of the 1960s, but it’s a term rooted in a very Anglophone-Boomer conception of what science fiction is or was, and as such it’s a great way to start a flame war. often resorted to the “objective” perspective, simply telling the reader a bunch of stuff about the world; contemporary authors are better at dressing such material up as the observations and experiences of a given character.

Any given part of a science fiction story might be operating anywhere along our map’s Y-axis — but the genre is perhaps unique in how it can incorporate “objective” exposition alongside a more subjective literary narrative. Exposition can operate anywhere along the X-axis of scale, too, though it is more prevalent at the macro end; micro worldbuilding is more effectively (and easily) delivered through subjective perspectives. One medium is thus capable of ranging all across the map: the most “narrative” form of futuring has a variety of modal tricks in its toolbox. Other media are more restricted in their range of modes and affordances, but can access advantages and capacities beyond those of text.

Now consider the diegetic prototypes of “classic” design fiction: designed objects that implicitly belong to some future world. These operate on the micro end of the scale axis. Where they fall on the perspective axis is an open question; they might, for example, be seen as working a sort of second-person perspective (i.e. treating the viewer as a “you”, a possible user of the object, and thereby drawing the viewer into the future the object purports to belong to). It seems reasonable to pin this perspective toward the subjective end of the scale; the materiality of a prototype prompts the viewer’s identification with it as a thing they might use, forming a “cognitive bridge” See Auger, “Speculative design: Crafting the speculation” to the implied future.

However, design fictions can operate at other scales and perspectives: Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby’s United Micro Kingdoms The UmK is a deregulated laboratory for competing social, ideological, technological and economic models. http://unitedmicrokingdoms.org works in a more macro and objective manner than, say, Superflux’s Drone Aviary. Through a series of ongoing installations, films and publications, the project aims to give a glimpse into a near-future city co-habit with“intelligent” semi autonomous, networked, flying machines.

—Superflux, “Drone Aviary” Both examples rely on static images and/or prototypes, but—crucially—also deploy expository text to provide a frame for the visual and material elements. Even though the visual/material aspects of UMK and Drone Aviary are essential to their worldbuilding effects, those effects would be more limited without the text. As another example, Tobias Revell’s New Mumbai New Mumbai chronicles the fictional journey of a documentary filmmaker to the Dharavi slums of India in order to film a strange phenomenon involving genetically engineered mushrooms. The fungi serve as a new type of infrastructure providing heat, light and building material.

—Tobias Revell, “New Mumbai”, Bio.Fiction Science Art Film Festival 2014 relies on its ersatz documentary video (a highly expository, i.e. “objective”, medium, despite the subjective narration by in-world characters) to situate its prototype images (which are at an architectural scale, rather than a human one). Video pushes a work toward the “objective” end of the Y-axis, thanks to the logic of the camera eye: the camera (or its director) takes a similar position to that of the self-effaced narrator in a detached third-person text.

If these examples can be seen as multi-media futurings, then what of an indisputably experiential project, such as Turnton by Time’s Up? A large futures installation, Turnton activates bodily experience through a literal immersion of the visitor in parts of a near-future port city, a physical environment to be explored in great detail. But it also incorporates text and scripted audio elements, and is no less experiential for that; indeed, its experientiality relies on the textual as much as the textural.

This dimensional approach shows how a single project might enrol multiple narrative modes (as plotted on our map above), with each (closely related to a particular medium) activating different scales and perspectives within the fictional future, which is thereby brought to life.

In Defence of Theory

Do we even need a theory of futuring? And if we do, what for?

Theory, as I see it, is descriptive rather than prescriptive: the dimensions and axes above are not meant to instruct practitioners in the “correct” or “best” way to do futuring, but rather to provide ways to compare its effects, and how those effects are achieved. It is my hope that such a framework can guide practitioners in their choices of medium and narrative strategy when developing new projects, as well as guiding the work of taxonomy and critique, the feedback loop that evolves the practice as a whole.

The heart of theory, meanwhile, is reflection and reflexivity — and the social, narrative, and experiential turns in futuring have brought reflection and reflexivity back to a space from which they’ve too long been exiled.

Theory is not a strait-jacket, but a wingsuit.

Further reading & references

🝓